Cars That Run on Trees

Wood-burning cars may seem like a steampunk fantasy or the backyard obsession of some mad tinkerer, but at one point they were commonplace in many parts of Europe, and the technology that powers them still finds practical applications today.

Cover photo: Johann Linell with the Volvo he and two friends retrofitted with a gassifier. In 20 days in 2007, they drove 5,420 kilometres around Sweden on the power generated by seven cubic metres of wood. (Photo courtesy of Johann Linell.)

Deep in the forests of inland Sweden, Johan Linell pulls over, his engine dead. He and two friends leave the vehicle and fan out through the trees, returning with arms full of fir cones and dead wood. At the back of the car Linell unhinges the top of a tall steel box that towers from a hole in the boot. Smoke billows, and flames follow as he dumps the foraged wood inside. From the bottom of the tar-stained stack, thick, welded pipes clamber over the car’s body and snake to the front bumper, where they enter the engine like a patient’s feeding tubes. Within minutes, the car comes to life, smoothly running on solid wood.

For a brief moment, 70 years ago, nearly all civilian vehicles in Europe worked this way. As the Second World War dragged on and petrol became ever scarcer, wood emerged as the primary alternative transportation fuel. By 1945 around one million European vehicles were powered by wood gasification, using modifications similar to those on Linell’s Volvo. The operating principle is remarkably simple: by burning a barrel of wood or coal until it develops a core temperature of between 900° and 1,200°C (1,650° and 2,200°F), then restricting the fire’s supply of air, gasifiers produce flammable carbon monoxide that can be cooled, filtered, and delivered directly to a normal car engine.

Wood-powered automobiles were invented in 1905 by Thornycroft, an English car company, but it was another 20 years before Georges Imbert, a French chemist, made wood-gas travel a practical possibility. With a redesigned burning chamber that used suction from the engine to pull gas downward through the hot core of the burning logs, his model could create a great deal more carbon monoxide than previous iterations. It also ensured a steady burn, as gravity and the vibration of the vehicle would shake ash loose from the pile, settling new fuel into place. By the 1930s, four European governments were actively researching Imbert gasifiers with a view to their use in mass transportation: politically neutral Sweden and Finland were looking to achieve fuel autonomy in a volatile region; Mussolini’s Italy, under a League of Nations trade embargo following its invasion of Ethiopia, sought an alternative fuel source to oil; and Nazi Germany was preparing for war.

Even wood-gas cars need a supply infrastructure: in 1945, Finland had 70 wood-preparation factories, and Germany had thousands of wood depots specifically for vehicle fuel. Out of the 17 places where Linell and his friends stopped for wood during their trip, only four had ready-to-use, pre-chopped wood.

Germany’s descent into the abyss is surreally documented in surviving copies of the state-sponsored car magazine Motor Schau. Both pro-Nazi propaganda and banal motoring periodical, its 1939 editions feature racing drivers wearing SS insignia, the Wehrmacht testing motorbikes, and swastika-festooned rallies celebrating the Kraft durch Freude car, or Volkswagen Beetle. In 1940, as each monthly issue announces the fall of another European capital, features on wood-gas vehicles begin to appear, touting the technology as a fuel of national pride that will liberate Germany from dependence on foreign suppliers. In the issues between 1941 and 1942, as the needs of the military caused Germany’s civilian oil supply to drop by more than 50%, the pages of Motor Schau fill with multiplying advertisements for gasifiers and also hard alcohol.

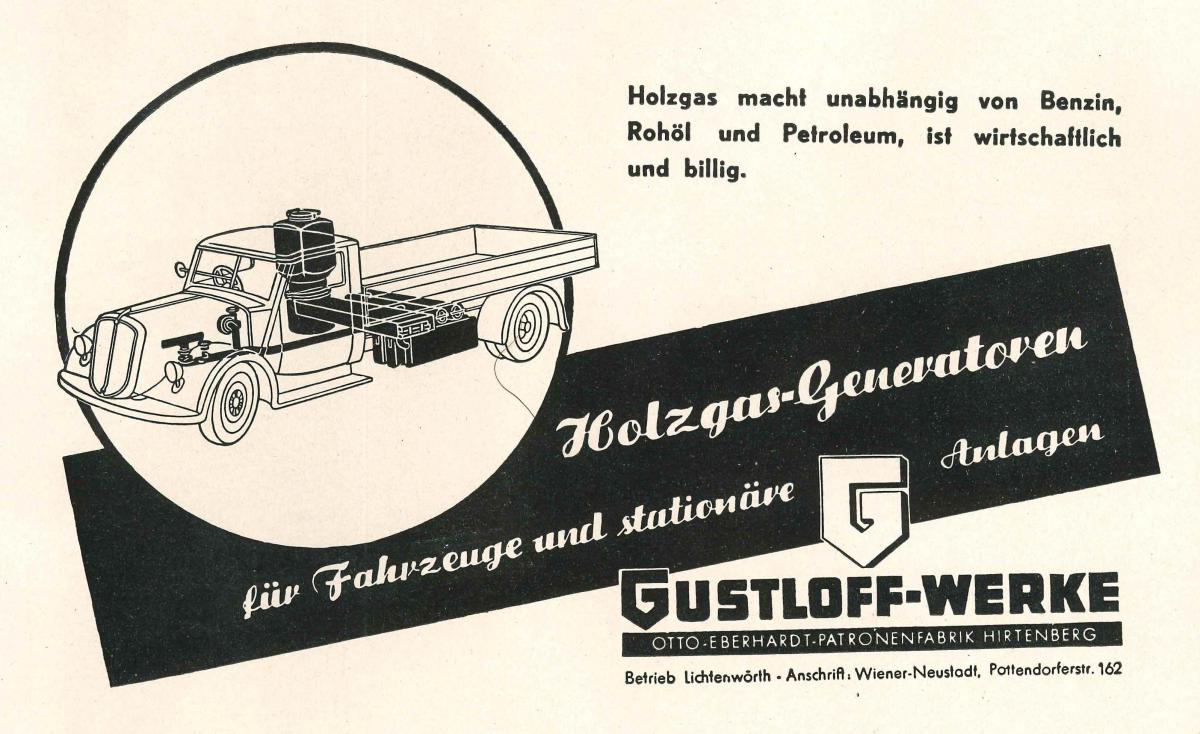

‘Wood-gas is cheap, economical, and ends your dependence on gasoline, crude oil and petroleum.’ So reads the advert from Motor Schau, a Nazi-era motoring magazine. Wood-gas powered transport holds a special appeal for totalitarian regimes seeking independence from world trade, and is still used in North Korea today. (From Motor Schau magazine, 1941)

By 1943, the distinctive, tall, cylindrical stoves were mandatory on most vehicles in Nazi-occupied countries, as liquid fuel resources were routed straight to the armed forces, particularly the Luftwaffe. In 2013 Greek mechanic Alexandros Topaloglou told researcher Alexia Papazafeiropoulou that despite the wartime restrictions, Greeks maintained a lively market in black market petrol, fooling officials by lighting gasifiers on their cars just before approaching German checkpoints. As Germany began to lose territory in 1944, at least fifty Tiger tanks were retrofitted with wood-gas units, and punishments for driving on petrol without written permission from the regional General—even for the military—became brutal.

Adolf Hitler inspects a wood-gas vehicle. When originally published in a 1941 edition of Motor Schau magazine, the image ran above a quotation from the Nazi leader: ‘These vehicles will still have special significance after the war because increasing motorisation will mean we never have enough oil, which leaves us dependent on imports. This fuel from the homeland is good for the homeland’s economy.’ (From Motor Schau magazine, 1941)

Hitler’s personal views on wood-gas cars can be read in a 1941 issue of Motor Schau, alongside merry photographs of Der Führer at a demonstration of Mercedes-Benz gasifiers. ‘These are vehicles that will have special significance after the war,’ he said. ‘Oil comes from abroad, but this is the fuel of our homeland.’ Four disastrous years later, Berlin’s gasifier cars would indeed take on a grim symbolism. During the savage winter of 1946, they rusted uselessly on the streets as Berliners smashed furniture and uprooted trees, desperately searching for firewood in the rubble of the German capital.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.In the early 2000s when Linell decided to make his own wood-gas vehicle, he had only seen one once. Wood-gas vehicles in Europe are the exclusive domain of hobbyists, and his only source of parts and information was a local phone-in radio show called Serk I Fin, or ‘Search and Find’. On-air, Linell outlined his plan, and was matched with Inge Nyman, an elderly listener who had lived through the Second World War and still had gasifier elements left over from the period. It was a breakthrough since, astonishingly, there was little else available, even though in 1945 there were over 60,000 wood-powered vehicles in Sweden, including boats, buses, tractors and a quarter of the country’s motorbikes.

(Photo courtesy of Johann Linell.)

Today hobbyists share advice on the Internet, and modern technology enables ‘woodgassers’ all over the world to benefit from the experience of authorities such as Finland’s Vesa Mikkonen and the Netherlands’ pseudonymous ‘Dutch John’. The gasifiers they build, however, still share much in common with their predecessors from the Second World War and are notably finicky, demanding an intimate knowledge of their constructions, quirks and temperaments. In Dutch John’s words, ‘the only person who can drive a wood-gas car is the person who made it’.

Even mass-produced versions from the 1940s, such as the 1943 German 3TO Opel Blitz Lastwagen, came with thick, illustrated operating manuals which detail how every week the Lastwagen needs its grate cleared and thoroughly washed, and every month its loose cork gas filter has to be removed, cleaned and reinstalled. Starting its engine, though a 20-minute process, mainly involves putting a match to the wood stack, but controlling gas and air flows around the engine, crucial for such challenges as driving uphill, traversing a valley, or stopping for more than three hours, requires mastering combinations of four levers and a pull-knob. Gasification produces significant quantities of nitrogen, an inert gas which dilutes the fuel mixture, with the result that wood-gas cars are low-powered, and coaxing the best out of them—through judicious adjustment of valves and vents—is as much an art as a science.

‘When you drive slowly, you see more,’ says Linell. ‘It’s almost like the country transforms according to your car. I sensed the same thing a year earlier, when I rode 500 km (311 mi) on a moped I had converted to run on ethanol. You see a whole new world.’

There’s no reason, however, why gasification technology has to stay stuck in the last century, which is why Finnish wood-gas enthusiast Juha Sipilä built the world’s most advanced wood-gas vehicle, the El Kamina, a modified truck containing a fully automated gasification system controlled by a computer embedded in its dashboard. Though only a prototype, his is a wood-gas car that can be driven by anybody. Sipilä is more than just a hobbyist; he is a firm believer in renewable energy and in enabling people to live ‘off the grid’. He is also the founder of Volter Oy, an energy company dedicated to exploring wood gasification, as well as the creator of the ten-house eco-village Kempele, and, as of May 2015, the prime minister of Finland.

In 2010, Finnish society held a passionate public debate about a possible return to wartime fuel substitutes, particularly wood gasification. In 1945, 80% of vehicles in Finland—46,000—ran on gasifiers, consuming more than 2,000,000 m³ (70,630,000 ft³) of wood in 1944 alone. The whole transition to a wood-based transport system took place in just two years. Now, innovations such as the El Kamina show that many of the shortcomings of the process can be overcome with new technology. Most persuasive of all, with 23 million hectares (88,800 mi²) of boreal roundwood forest and a population of only 5.5 million, Finland is one of the few countries in the world where trees could be a truly sustainable fuel source.

Johan Linell cleaning the cooler on his wood-gas Volvo, which he made from an old steel diesel tank. Cooling the gas makes it denser and condenses water out of the fuel mix so that more power is delivered to the engine. After use, Johan found the inside of the cooler would be coated with a mysterious creamy substance. ‘It reminded me of Vaseline.’ (Photo courtesy of Johann Linell.)

Jaarno Haapakoski, the CEO of Volter Oy since 2011, explains that a family of six living in the model village of Kempele, which is powered and heated by a large wood gasification plant, requires only 20 m³ (706 ft³) of wood per year. According to Metla, the Finnish Forest Research Institute, Finland’s forests produce 104.5 million m³ (3,690.4 ft³) of new wood every year, almost enough to cover the energy needs of everybody in Finland. What’s more, burning trees is a ‘closed carbon loop’: the carbon dioxide that trees release when they are burned is roughly equal to the carbon dioxide they pull from the air as they grow.

There is a downside. Wood-gas is primarily carbon monoxide, and carbon monoxide is odourless, lighter than air and exceptionally poisonous. At atmospheric concentrations of just 0.5% it can kill, and a mere 0.03% is enough to cause unconsciousness. In one incident in wartime Helsinki, passengers were seen entering a waiting taxi on a cold day. Ten minutes later, the taxi had not moved, and passers-by opened the doors and found the occupants unconscious, poisoned by a gas leak into the closed car compartment. A third of Finland’s estimated 25,000 wartime carbon monoxide intoxication victims were affected while they were driving their cars, often with disastrous results, and wartime approaches to carbon monoxide detection were often crude. Denmark, for instance, installed caged mice or canaries near gasifier units to test for fatal gases. But today Haapakoski is unworried. Detectors are far more sophisticated, he says, and burners can be built with failsafes and alarms.

Nor is this the first wood-gas renaissance. Between its resurrection in 21st-century Finland and its heyday in wartime Europe, interest in the technology blossomed in the 1970s in the wake of the global oil crisis. Some of the interest was defensive, such as that of Sweden, which developed three types of emergency gasifier ready to be mass-produced in times of crisis. But much of the interest arose in the developing countries with the most urgent need: rural Asia, Africa and Latin America.

The potential appeared huge. Any carbon-based waste can be gasified, whether rice husks, wheat chaff, walnut shells, fruit seed, sawdust, straw, peat or corncobs. Filters can be made of oil, charcoal, cork, water, cloth, porcelain chips or sisal. And with the right expertise, efficient gasifiers for cars or electrical generators can be built from oil barrels and rusty pipes. Large gasifier electricity plants have been effective in specific locations, such as the sawmills in Sapire, Paraguay and South Africa’s Eastern Cape, a coconut desiccator in Sri Lanka, powered by gasified coconut shells, or the several hundred small, rice-husk-gasifying power plants in China. Emergency units like the Power Pallet, a gasifier generator developed in California, have recently shown promise as a means of disaster relief in Liberia. But in the present day, methane generation from sewage has proved far more successful as an off-the-grid, alternative energy source. In poor countries, burnable solids like nut shells and straw can still be commodities, however cheap, while methane is created from waste.

Johan Linell and his friends Mikael Anderberg and Martin Johansson began building their wood-gas Volvo at the beginning of 2007. By July, it was ready, and they set off on a 5,420-km, (3,368 mi) wood-powered trip across Sweden. The trip took 20 days despite the car’s top speed of 90 kph (56 mph), because stopping every 50 km (31 mi) to refuel their original 1942 gasifier tank made progress slow.

In part, their route was dictated by the need to find wood. Foraging for fir cones and wind-felled trees can only be done in an emergency. Effective gasification requires wood that’s less than 20% water, meaning wood has to be properly dried out before it can be used. Wet wood not only reduces the power of the engine by adding steam to the mix and using up heat for evaporation; it can also cause ‘wood hang’ by burning so slowly that the wood fails to settle into the burner. ‘It’s like it bridges up and won’t fall down to where the fire is,’ explains Linell. ‘The centre gets cold, the gas creation process stops.’ It can also spread intense heat to the wrong parts of the system. ‘If you’re unlucky,’ says Linell, ‘it melts them.’ And if you are forced to forage, you can’t just use anything. ‘If you find a dead tree that’s a little bit dried up, you can use it, but it can’t be a pine tree,’ he says, ‘it has to be a fir tree. A big, dead Christmas tree. Not like one you’d have at home. A big one.’ Gasifiers cannot burn all shapes and sizes of fuel, either. Evenly sized pieces of wood ensure a consistent rate of combustion, necessary to avoid ‘pressure drop’, a sudden loss of power. On their journey around Sweden, Linell and his friends towed a trailer carrying an improvised wood-chopping machine made of a chainsaw, a piston, and an old car engine.

(Photo courtesy of Johann Linell.)

The trip left Linell with questions: ‘I was thinking, “Can I do something with this knowledge? Can I make a profit? Start a business?” I could see that gasification just isn’t good for cars. It functions, but it’s demanding. With a modern lifestyle, it’s too much work, it takes too much time, and it’s too dirty. Even if you had the infrastructure, I don’t think people would use it.’ Agricultural applications, however, looked promising, essentially because ‘you’re more stationary—you can have your own pile of wood.’ Linell applied his skills to a 68-year-old tractor, and converted it to run on trees knocked down by the wind. He decided to spend the whole of 2008 living a self-sufficient, carbon-neutral life on his family farm in Dalarna, Sweden, cultivating potatoes, carrots, beetroot, turnips and lettuce with his new machine. In the end, there was no business plan, and he didn't make a profit. ‘I just picked up an old tractor, and some wood from the woods, and got to work.’