Innovation Behind Bars

Behind bars, where resources are scare but time is plentiful, inmates have to make what they need from the materials on hand; toilet paper, toothbrushes and headphone wires can be put to new and sometimes dangerous purposes.

Cover photo: Stateville Correctional Center is a maximum-security state prison for men in Greater Chicago. This part of the prison was opened in 1925 based on Jeremy Bentham’s 1787 design for the panopticon prison house. It is used for segregating inmates from the general prison population and for holding inmates who are awaiting trial or trans fer. Stateville’s 1,300 employees guard 1,506 inmates.(Photo: Doug Dubois & Jim Goldberg/Magnum Photos)

Roscoe Jones spent 11 years in solitary confinement in Angola, Louisiana, the biggest maximum-security prison in the United States. When he finally emerged, he took with him the ideas for two inventions. One was a board game that he created, produced and even sold to visitors at prison fairs. The brightly coloured, hand-drawn Serving Time on the River: The Harsh Realities of Prison Life casts players as inmates in Angola, forced to run an unending gauntlet of ‘Unavoidable Circumstances’ brought on by rolls of the dice. The harsh realities, as players quickly discover, include sexual assault, scalding, hurled faeces and a bludgeoning with a sock full of batteries. Gamers must serve their sentences, but even as they plough through fighting, theft, punishments, gangs and self-mutilation, the game may end, apropos of nothing, with ‘Killed in Prison’ or ‘Suicide’. Attending self-help programmes, informing on other inmates or contracting a severe chronic disease can earn early release, but the odds are stacked well against it. What’s more, some characters, like Jones himself, are in for life. They have to play the game, but can almost never win.

Jones created the game to give others a taste of what it was like to live behind bars. His other invention was born from pure boredom. After years alone with nothing to do but smoke, Jones became obsessed with the idea of a self-extinguishing cigarette. Using a small disk of metal from a coke can, a nail from his prison locker and a piece of thread, he invented a device that would put out a cigarette as it burned down. He had the idea patented and spent four years trying to sell it to tobacco companies from behind bars. His product was rejected.

Rolled magazine pages, hardened with soap and salt, can be sharpened into a makeshift knife or ‘shiv’. In the event of an inspection the weapon can be disposed of by unrolling it and flushing it down the toilet.

Inmate ingenuity has been a phenomenon since at least 1780, when William Addis, an inmate in Newgate, London, stuck bundles of horse hair into a bone to create a prototype for the first mass-produced toothbrush. Had Jones found himself in a Chinese prison, things might have worked out differently. An investigation by the Beijing Youth Daily newspaper revealed in January 2015 that Chinese prisoners can have their sentences reduced in exchange for patents that ‘provide great contributions to the state and society’. Nan Yong, for example, the former head of China’s national football league, now jailed for corruption, has filed patents for four innovations in one year. A former health bureau secretary has been awarded 11 during his incarceration.

Chess set by Temporary Services following Angelo’s instructions. “I owe my knowledge of the inventions and tricks presented here to my many cellies,” writes Angelo. “Victor, one of my first cellies, introduced me to the concept of making chess pieces from toilet paper mache. Ron, who I taught to make paper mache chess pieces, turned out exquisite sets just as fast as the cops could confiscate them, with each succeeding set becoming more elaborate and beautiful – his reasoning being, it's the cops' job to keep us down, and ours to show them that they can't.” (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

This spurt of creativity may not be all it seems: investigators also uncovered a whole industry of unscrupulous patent agencies offering to rewrite existing patents under prisoners’ names for fees from US$1,000 to 10,000 (€880 to 8,800). But even if its policies are flawed, surely China is onto something. Even without the incentive of freedom, inmates are driven to create out of necessity, boredom, self-preservation, defiance of the system or the need to assert their identities. If Jones’ cigarette invention was a way to make his life fractionally more comfortable, his board game told his story.

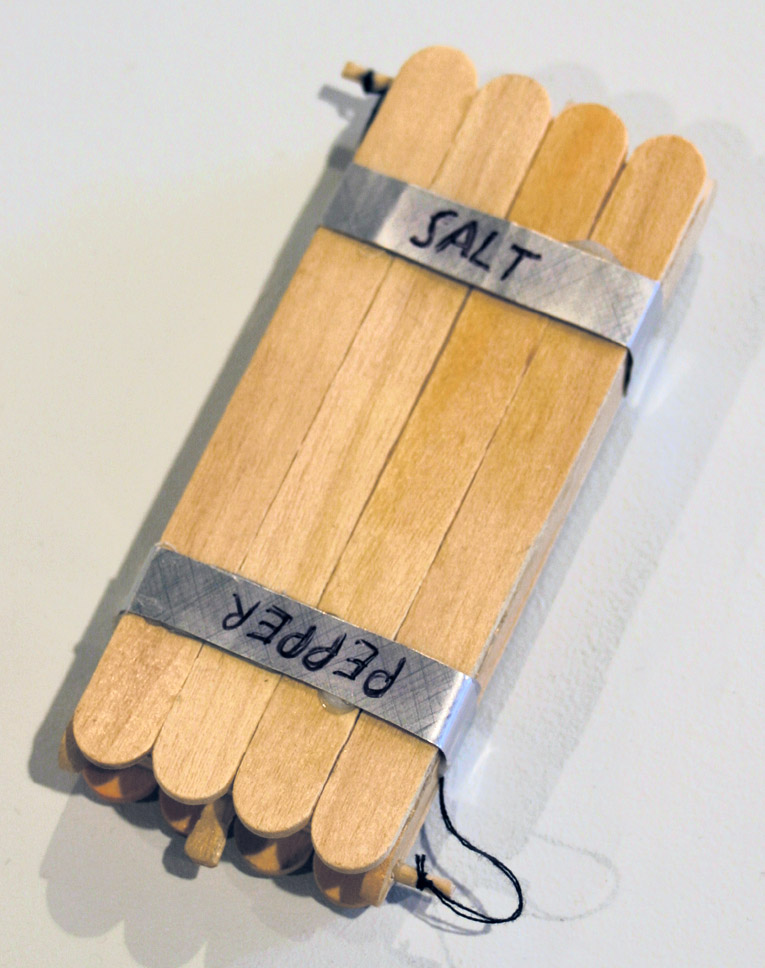

In 2003, a Californian inmate known only as Angelo published a book with the Chicago art collective Temporary Services. Without revealing his name, location, or the crime for which he was incarcerated, Prisoners’ Inventions paints an extraordinary picture of life inside, told through the improvisations Angelo and his cellmates used to improve their situation. With detailed pen sketches, Angelo shows how inmates cool drinks by putting the can in a wet sock and setting it in front of the ventilator, how they make coat hangers out of pieces of ripped sheet and rolled newspapers, how they wash in a toilet, drink from a toilet, brew in a toilet and cook in a toilet. Not all the inventions are born out of dire necessity. Angelo details the manufacture of carefully designed and proudly kept salt and pepper dispensers made from Bic lighters or ice cream sticks. One of his cellmates tiled their entire two-man, 6 × 9 ft (2 × 3 m) cell with playing cards held under a thick layer of high-gloss floor wax. Another built a working mini-lathe. On hot days they practise ‘pooling’, blocking all drainage points and turning the taps on to flood their cells. Angelo’s accompanying drawing shows a man floating on his back by a bunk bed, reading a newspaper.

Even an act as simple as trading candy can mask payment for protection services. In the New Mexico Department of Corrections, however, some candy is itself illegal: chewing gum is contraband, because it can be used to make a mould of a key.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Angelo first connected with Marc Fisher at Temporary Services in 1990, responding to a fanzine Marc had published called Primary Concern. Over time, explains Temporary Services, ‘Angelo casually mentioned inventions in his letters without really thinking much of them’, once sending Marc ‘a set of hard, sugar-infused toilet-paper mache dominoes’. They suggested the idea of making a booklet together, and months later received ‘a mind-blowing package of illustrations’, many of which are among the nearly 80 images in the final book. Thirty of the inventions were reproduced by Temporary Services for an exhibition which included an actual-size replica of Angelo’s cell, constructed according to his blueprints.

In prison, any item found to be altered is contraband and can be confiscated. Angelo’s cellmate Earl “acquired a radio that had no case or speakers but worked very well using the earphone jack,” writes Angelo. Using the backings from writing tablets, white glue, and a lot of black magic marker, he constructed what looked like a complete case. “Most important, it survived cell searches.” (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

‘Everything in the book is considered contraband,’ says Temporary Services. ‘Everything was done through the mail.’ There were also ‘an enormous number of drawings that [Angelo] wanted to send, but that were taken away from him […] Property in prison is generally unstable and susceptible to theft by both guards and fellow prisoners.’ In Angelo’s introduction to his book, he writes, ‘If some of what’s presented here seems unimpressive, keep in mind that deprivation is a way of life in prison. Even the simplest of innovations presents unusual challenges, not just to make an object but in some instances to create the tools to make it and find the materials to make it from. The prison environment is designed and administered for the purpose of suppressing such inventiveness.’

This is a replica of Angelo’s cell, built by Temporary Services according to measurements that he posted to them. The two-man unit is six feet by nine, and is where prisoners spend almost all of their time. Everything a prisoner owns must be kept in one of the two open storage lockers on the wall. Modifications to the cell are forbidden, including putting up a curtain between toilet and bunk. (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

As dramatic as this sounds, his claims are borne out by the prison guards themselves. On correctionsone.com, a website for correctional officers, Joe Bouchard, a member of the Board of Experts for The Corrections Professional, lists some examples in an article titled ‘What is Contraband?’: ‘Homemade weapons, gambling paraphernalia, excessively metered envelopes, weapons, drugs, food and whatnot’ are contraband. ‘An altered item, such as a hollowed out law book’ is contraband. ‘Excessive amounts of allowable property’ (such as postage stamps) are contraband. Even information can be contraband. In short, ‘In a prison, almost anything can be contraband.’

‘Contraband is power for prisoners,’ Bouchard continues. ‘It allows them to gain power over others. For enterprising prisoners, trade in illicit goods and the performance of prohibited services are the building blocks of power. With planning and work, the smallest gambling enterprise has the potential to develop into a large trading empire inside the walls. With such an empire, inmates can procure weapons, narcotics, loyalty and outside help, all of which can destabilise the security of any institution.’ Accordingly, anything a prisoner owns or makes is subject to confiscation at any time, though prison guards may practise a judicious amount of tolerance.

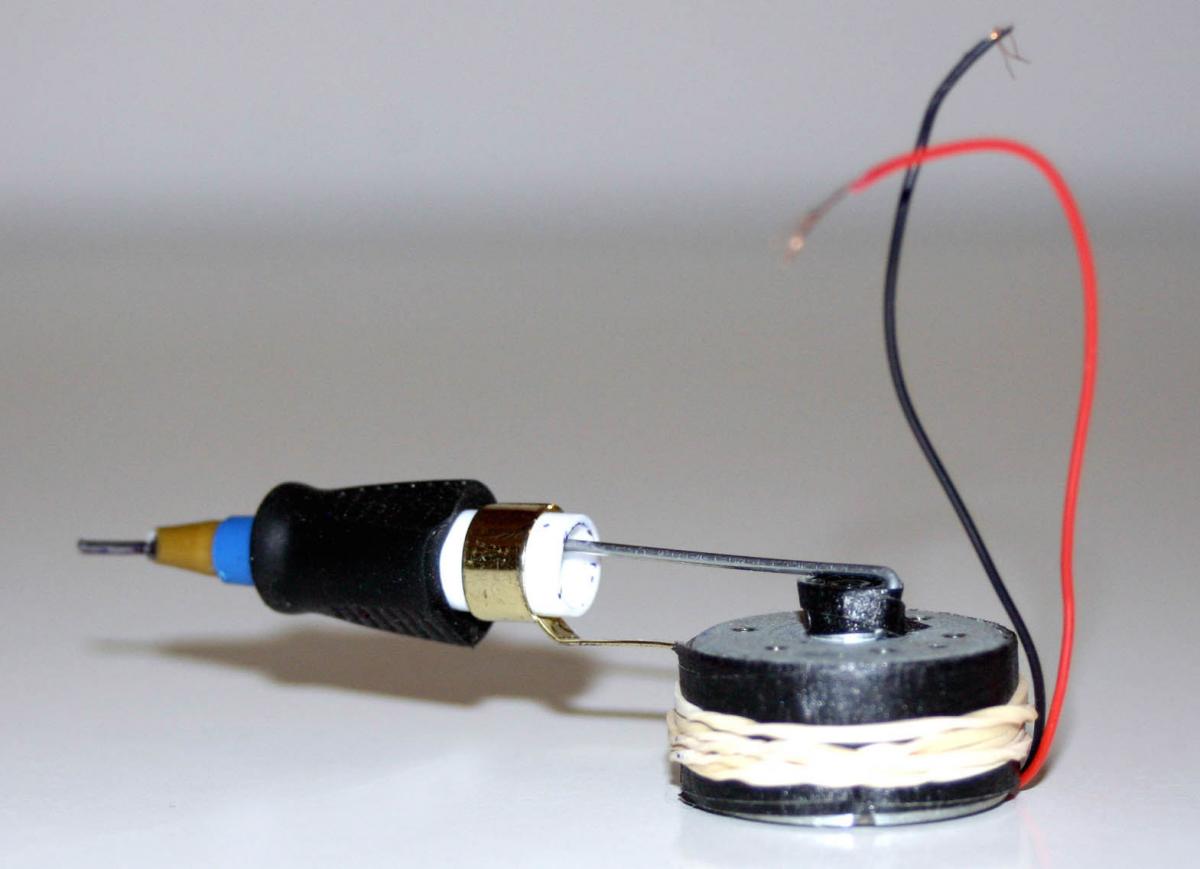

An electric cigarette lighter, reconstructed by Temporary Services according to plans by Angelo. When the circuit is completed, two D-cell batteries heat the exposed filament. Improvised lighters became common in the Californian prison system after 1995, when the government banned smoking in state buildings. (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

‘It’s an unspoken rule,’ Angelo agrees, ‘that as long as inmates don’t flaunt what they’re doing, many of the staff will turn a blind eye.’ As a basis for daily life, however, this offers scant protection or comfort. In a world where personal property is never secure, inventions become a way for prisoners to salvage their dignity and sense of individual agency. Angelo’s cellmate ‘Ron’, who Angelo taught to make paper mache chess pieces, ‘turned out exquisite sets just as fast as the cops could confiscate them,’ writes Angelo, ‘with each succeeding set becoming more elaborate and beautiful—his reasoning being, it’s the cops’ job to keep us down, and ours to show them that they can’t.’ Naturally, all of the devices in Prisoners’ Inventions are considered contraband ‘subject to confiscation in routine cell searches. But inmates are resilient if nothing else—what’s taken today will be remade by tomorrow, and the cycle goes on and on’.

It’s in everyone’s interest that guards confiscate improvised knives, which can be made from ventilator grills, toothbrushes, pieces of bunk bed, or even plastic bags, melted down and rolled to form a sharp point.

The complexities of life in the American correctional system can make that cycle particularly absurd. Every cell, for example, needs a washing line in order to dry towels after showering, and every prison explicitly forbids them because of their multiple potentially dangerous uses. In Angelo’s experience, string was always impossible to get hold of, so inmates ripped up their sheets to make clothes lines, which would, in turn, be ripped down by guards. Under US law, sheets, along with shelter, clothing, food, hygiene supplies and stationery, must be provided to every prisoner, so more sheets would be delivered, which would immediately be ripped up to make new lines.

Most prisoners pass the time working out, smoking, eating, drinking and masturbating, and Angelo describes improvised objects for all of these activities. He explains how plastic refuse bags filled with water, tied shut and wrapped with shirts are used as weights, and how rolled blankets, wastebasket liners, warm water and baby oil are used to build sex dolls. A wide range of cigarette lighters are described in depth as well, the two most extraordinary of which both use a wall socket. With an improvised plug made from paperclips or razor blades, one model runs electricity simultaneously through a coiled wire serving as a heating filament, and a glass of salt water serving as a resistor. The other model uses the graphite rod from a pencil to complete a circuit against a paperclip plug, creating a bright spark. Both methods come with Angelo’s recommendation, as they are less likely than others to blow the fuse on the whole cell block, cutting off power to neighbouring convicts’ TVs.

This tattoo gun uses a Walkman cassette motor to vibrate a paper clip attached to the barrel of a pen. The needle is a sharpened piece of wire, and ink is taken from ballpoint pens. “In terms of imagery,” writes Angelo, there was “a tremendous emphasis on skulls, sad clowns, naked women in bondage or sexually submissive poses, and demons and dragons. I can’t recall ever seeing any sort of humor employed.” (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

A universal problem for all prisoners, according to Angelo, is the airflow from the air conditioning duct, which is, ‘invariably […] too strong, too weak, too hot, too cold, or some combination of the four’. He lists a number of remedies, including packing wet toilet paper onto the vent, plugging up each of its holes with tiny paper plugs, or stitching a piece of cardboard or chipboard onto the front of it, with a window cut out so that a separate flap of material can be used to adjust the flow. Angelo also explains how to shade a cell’s light, and stresses that it must never be entirely covered, ‘as a small concession to the rules’, and, as his onetime cellmate ‘Randy’ expressed, ‘to provide the sense of control and authority that staff likes to feel’.

In her 2015 project Prison Gourmet, Californian artist and activist Karla Diaz confronts the subject of prison food in unsettling depth, collecting prisoners’ own recipes for dishes made using the limited ingredients available from the jail commissary and the vending machine. Denied pots, pans, or even the most basic kitchen implements, prisoners use plastic bags, clothes and towels to prepare meals. One recipe for ‘orange chicken’, Diaz notes, uses strawberry jam, sugar, water and powdered Kool-Aid to make a sauce to pour over pork rinds. The prisoner who invented it told Diaz that he didn’t eat it for the taste, but to invoke the memory of the real orange chicken that he used to eat with his daughter.

Made by Temporary Services according to Angelo’s extensive instructions, these dice are made from wetted toilet paper, with a shell of hardened sugar water or Kool-Aid. Tom, one of Angelo’s cellmates, became convinced that Angelo loaded the dice as they were made. To even things up, Tom built his own die-casting table for them from soup cartons and masking tape. (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

The ability to make a hot drink is also important. Immersion heaters known as ‘stingers’ are crucial prison equipment, and though they’re sold in some prison canteens, in other facilities they have to be made from scratch. One of Angelo’s cellmates, ‘Little John’, was new to prison when Angelo met him, and was thrilled by the improvised technology created behind bars. He became an expert in producing stingers that used a jury-rigged electrical plug (made of safety-razor blades bound to a piece of eraser by a melted strip of plastic) to power a heating element (also made of razor blades and plastic) via earphone wires. Little John would make a stinger for whoever wanted one, according to Angelo, and ‘could assemble one in about an hour’, given access to the right materials.

For a wide variety of projects, toilet paper is one of those ‘right materials’. Alongside its obvious uses, the paper mache that can be made from toilet paper is a prime resource for creating contraband. One of Angelo’s most extraordinary inventions was a cup made from an entire roll. After wetting the paper and moulding it around his fist, Angelo waterproofed the interior with cling film and allowed it to dry. This large, ungainly cup, still the shape and size of a roll of toilet paper, needed to be hidden from the guards, so he drew a large black circle on the bottom of it, explaining, ‘I took to keeping [it] in the recessed toilet paper holder in the sink, a deception that worked so well that for all I know the cup could still be in that cell, as I accidentally left it behind when I moved on.’

This replica of Angelo’s paper mache cup made by Temporary Services was made from an entire toilet roll, wetted, moulded, dried and then waterproofed with sandwich wrap. Angelo disguised it from guards by drawing a large black spot on the bottom and placing it in the toilet paper holder under the sink. (Photo courtesy of Temporary Services.)

Angelo finally left prison for good in late 2013 and settled in the Los Angeles area. By then, Temporary Services had already taken their exhibition of replicas of his work on tour to Massachusetts, Philadelphia, Berlin, New York, Leipzig and Athens, and wherever it went, current and former inmates recognised echoes of what have become universal designs, passed from facility to facility by word of mouth.

Brett Bloom from Temporary Services taught for two and a half years at a prison in Danville, Illinois. He would present Angelo’s book to students, who ‘would often critique our craft’ and ‘offer better solutions based on the things they had made’. Inmate invention is inevitable. ‘If a person likes to cook, make things, repair things, or otherwise solve problems by working with their hands and imagination,’ say Bloom and Fisher, ‘those impulses aren’t going to disappear if that person is sent to prison.’