Beyond the Baseline

While all eyes are on players’ speed, strength, strategy and showmanship, nearly invisible changes to their rackets can help them achieve a competitive edge over their opponents.

Cover Photo: On Sunday, November 20, 2016, Andy Murray beat Novak Djokovic at London’s ATP World Tour Finals to finish the year at the top of the rankings and cement his place at the very pinnacle of his sport. While nutrition, training, and his choice of coaches have all contributed to his successes, he really boosted his game by switching his main strings from Luxilon Alu Power Rough to Luxilon Alu Power in the summer of 2012. (Photo: Volkan Furuncu, Picture-Alliance)

On November 5, 2016, Andy Murray confirmed himself as the world’s number one tennis player. It is a remarkable achievement by almost any standard: not only did he become the first British player to reach the position since computerised rankings began back in 1973, but he also did it in an era considered to be one of the strongest in the sport’s history, fighting from the peripheries of the elite echelons, past the likes of Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic, to name just a few. In 2011 he was still the talented if volatile outsider who entered but never conquered the major tournaments, but in August 2012 he became the first British man to win the Olympic singles gold medal, beating Federer in an emotional final on home turf. The following September, he secured the biggest victory of his career, overcoming Djokovic in New York to become the first British man to win a Grand Slam final since Fred Perry in 1936.

Of the changes that account for this impressive transformation, one was visible and widely publicised: on December 31, 2011, Murray invited Ivan Lendl onto his coaching team—a valuable addition that had a substantial and visible impact on the player’s mindset and playing style. Another change was so subtle as to slip by unnoticed, even by those who know the game well. Like many players, Murray has long preferred a hybrid set-up where two different types of string are combined in one string bed: one for the mains (verticals) and another for the crosses (horizontals). While he continues to use natural gut in the crosses, in the summer of 2012 he switched the main strings from Luxilon Alu Power Rough to Luxilon Alu Power. A small change, perhaps, but its importance should not be underestimated. Alu Power is reported to offer more power on ball striking than Alu Rough, and although it must be noted that Luxilon does not mention any power difference in its advertising literature, the results are there for all to see.

The modification that Murray made is merely one piece of a far larger puzzle, just one of a plethora of options available to players looking to tweak their rackets in order to improve their games. ‘Touring professionals have their rackets customised to their specific needs,’ says Colin Triplow, a UK-based professional racket stringer. ‘It’s a highly important part of performance maximisation.’ Consequently, the specific rackets used by the world’s elite are not actually readily available to the public; rather, each racket is individually tailored to suit the player who uses it.

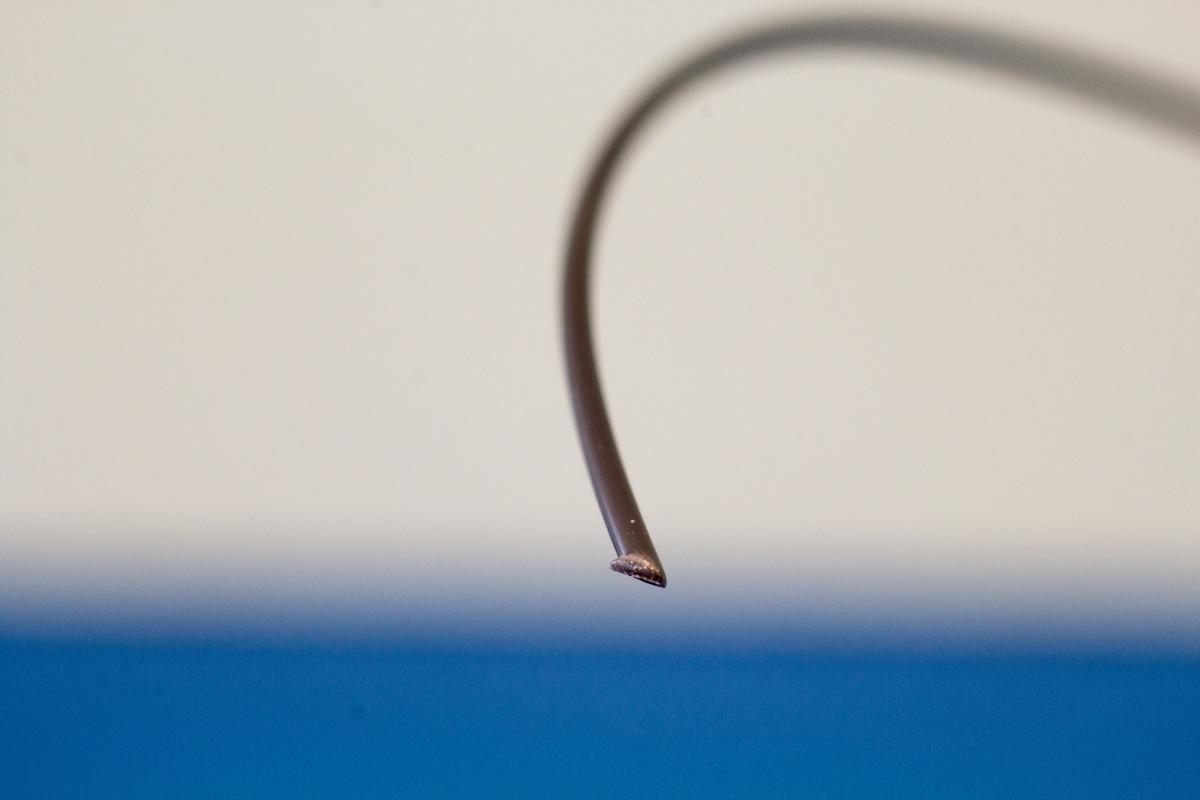

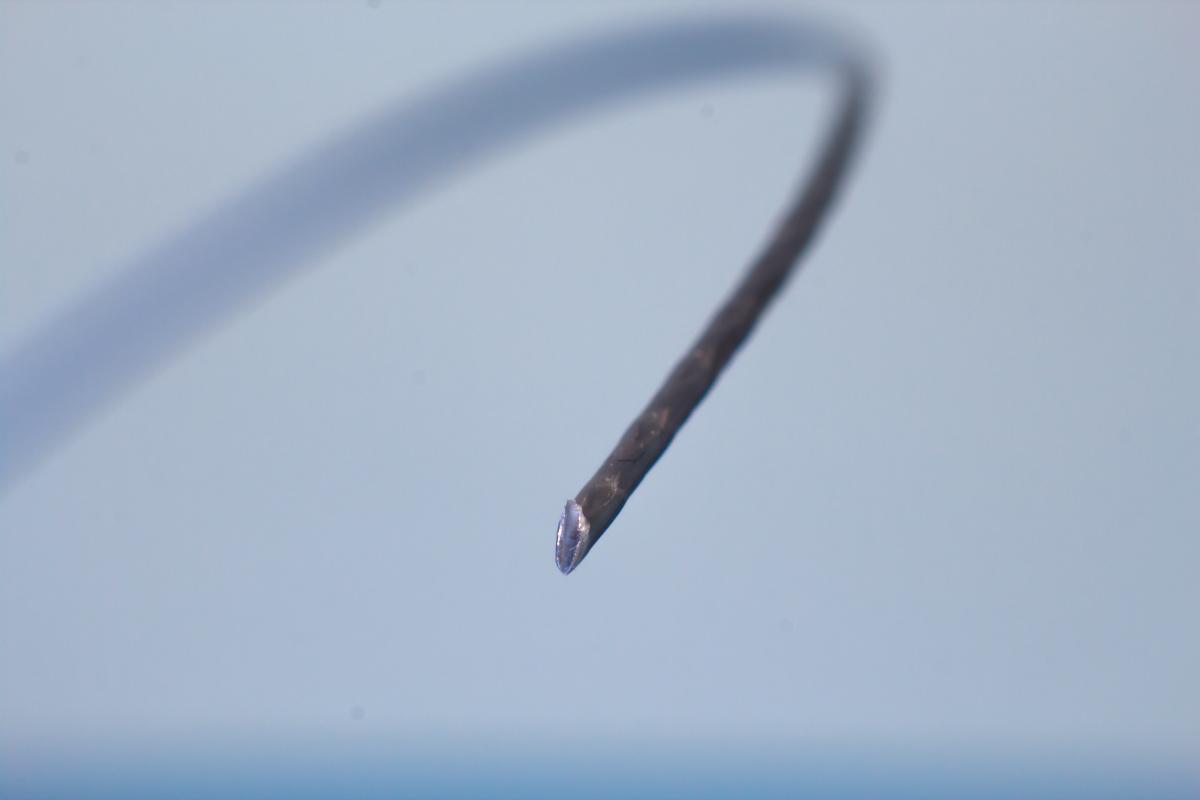

String type and string tension have huge implications on how the ball responds when it contacts the racket face. Traditional tennis strings (left) are smooth and circular, but recent years have seen a great rise in the number of shaped or textured strings (right) on the market. These strings are designed to maximise the amount of rotation on the outgoing ball by increasing the friction when the player swings across its trajectory. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

(Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

Take Mike and Bob Bryan, for example, arguably the finest doubles pair in the game’s history: ‘We’re very particular with our racket specifications,’ they say. ‘All our rackets are sent from our manufacturer to Tampa, Florida, where our frames go through a lengthy and thorough customisation process with the experts at Priority One, a customisation specialist,’ they add. ‘We have tinkered with everything from our grip size, racket length, swing weight and string density to even different kinds of cosmetic paint.’ The rackets they use now are heavier than the average model and also have a denser string pattern (i.e. more crosses and mains). ‘We feel we get more power and stability from the added weight and that we have more control with the added strings.’

For Andy Murray the road to the top of the men’s tennis world was marked by relentless dedication to honing his strength, speed, endurance, technique and tactics, but also to developing a racket set-up that enabled him to maximise his physical and mental performance. Nearly invisible modifications to his stringing were a critical part of his transformation into the number one men’s player in 2012.

The primary reason for these modifications is simple: as the line between winning and losing becomes thinner and thinner, even these slight changes become more and more important. As a result, players and their teams are becoming increasingly creative with the modifications to their racket set-ups as they look to maximise any competitive advantage over their rivals.

It hasn’t always been this way. Only in the late 1960s and early 1970s did string customisation begin ‘taking off’, Triplow says. ‘Before then, a racket was a racket and a string was a string.’ The only known earlier examples of racket modifications came in the thirties when players began using piano wire instead of natural gut in search of more durability, but this was an exception.

Almost all competitive players take several rackets onto the court for a match. While the rackets are likely to be identical in terms of almost all specifications (weight, balance point etc.), they are often strung at different tensions, which allows the player to adapt to the continually changing circumstances in a match, including temperature, tactics, and ball conditions. For example, when new, more lively balls are introduced, players will often switch to a racket with a higher tension in order to maintain control. (Photo: Volkan Furuncu, Picture-Alliance)

Then in 1976 Werner Fischer started playing with the spaghetti-strung racket following four years of development. It was, Triplow explains, an ‘extreme’ way to string, executed by reducing the number of cross strings from the standard 18 or ten to five or six thicker strings, and doubling the number of main strings by passing two thinner strings through each hole. He then inserted short sections of plastic tubing onto the main strings where they intersect the cross strings, creating a string bed that generated so much topspin that it was quickly banned by the International Tennis Federation (ITF). It wasn’t long before some of the leading names of the generation picked up on this breakthrough technique, including Ilie Năstase, who subsequently forced Guillermo Vilas to walk off court during an Aix-en-Provence tournament because the Argentinian could not deal with the spin on the ball. Fast forward a decade or two, and racket modification has now become a regularity, in many ways an aspect of the game that is equally important as nutrition or physical, technical and tactical training.

Modifications can be divided into two categories: those to the string bed and those to the racket frame. The former is far more common than the latter: the choice of the strings and the tension with which they are installed is customisation on the most basic of levels—and one upon which almost all players, like Murray, must decide. Many rackets today actually come without any strings on the assumption that the purchaser will wish to format the string bed according to personal preference.

Of all synthetic strings, co-polyester are the most prevalent. Co-polys, as they’re called, were born when Luxilon combined polyester strings with powerful element additives and created a string that supports performance by maximising the generation of spin. Nylon strings, in comparison, are reasonably receptive, but Kevlar strings are considered too stiff for competitive play. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

In 1874 tennis rackets were all strung with natural gut made from the outer layer of sheep intestines. Natural gut is actually well suited for tennis because ‘it is extremely powerful and offers great feel,’ says Roger Dalton, former Head Stringer at the Wimbledon Tennis Championships. Due to a shortage of sheep gut, cow gut has become the most prominent natural gut string on our shelves today, and ‘up until the early nineties, no professional would have been seen dead without natural gut strings,’ Triplow says. This all changed, however, with the development of synthetic strings that are cheaper, more durable high-performance alternatives to natural gut. They are made from three materials: nylon (relatively durable and affordable), Kevlar (too stiff to be used alone) or co-polyester (polyester combined with additives that enhance its performance). Still, many touring professionals continue to use natural gut, especially in a hybrid set-up with a combination of other strings.

Of the synthetics, co-polyester is by far the most prevalent, a perfect fit for an era where players battle it out from the back of the court rather than coming to the net: studies indicate that the average outgoing spin from a co-polyester string is 25% greater than from natural gut or other synthetics. In a sense, Luxilon ‘revolutionised the game,’ Triplow says. ‘As one or two players began to experiment, then the others began to follow suit. It wasn’t long until the majority of touring professionals were experimenting with these “co-polys”.’

The thickness—or gauge—of a string is an important consideration for competitive players. Selecting a gauge is always a case of compromise: a thicker string will offer increased durability but reduced ‘playability’, while a thinner string will snap more easily but is supposed to offer enhanced ball ‘feeling’ and control on ball striking, although some players prefer the feel of a thick string. Players can find a middle ground by adopting a hybrid set-up, i.e. using different tensions in the mains and the crosses. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

Recent years have also seen a rise in the number of players using shaped or textured strings instead of the smooth, circular strings that were used for many decades. Textured strings are constructed with the addition of an outer wrap which increases the grip of the string surface, while shaped strings have a hexagonal, square, octagonal, or triangular profile. Both are designed to maximise the amount of rotation on the outgoing ball by increasing the friction when the player swings across its trajectory. The effectiveness of textured strings is yet to be proven, but shaped strings are regarded by many as some of the best on the market and are highly popular with players like Nadal who are looking to maximise spin.

Another important consideration for string selection is gauge or string thickness since it has an impact on both ‘playability’ and durability, how the string feels when the player strikes the ball and how long it lasts before it breaks. The general rule is simple: a thicker string will give increased durability but reduced playability while a thinner string will snap more easily but is supposed to enhance the feeling of the ball on the strings. Nadal has been known to use a thick 1.35 mm (0.053 in) string on the basis that his heavy ball striking would cause any thinner gauges to break too quickly; in contrast, top-50 doubles player Dominic Inglot uses a thin 1.25 mm (0.049 in) gauge because he prioritises responsiveness over durability. Sampras even tested thinner squash strings in an attempt to increase the feel of his racket.

While there are hundreds of types of tennis rackets on the market, pro players rarely play with off-the-rack models. Weight and balance, string types and tension, grip size and shape— all must come together to create a racket that is an extension of the individual who wields it.

Finding a compromise is why many players use a hybrid set-up. Using one type of string or gauge in the mains and a different one in the crosses allows players to fine tune the playability, durability, responsiveness, and control of their string bed by combining the best qualities of a string while minimising its limitations. To give an example: in a uniformly strung racket, it is almost always the main strings that break because they move a lot more than the cross strings, so to counter this—to increase durability without compromising performance—many mid-tier players will combine a durable, thicker co-polyester main string with a softer natural gut or premium synthetic (i.e. nylon or polyester) cross string. This will increase the longevity of the string bed and reduce the stiffness of the mains. Top players will reverse this combination for a high-performance hybrid combination with reduced durability.

String tension is also important. Tight strings give control because they deform the ball more on impact, while loose strings give the effect of being more powerful because the ball dwells on the strings for longer and is released later in the swing motion. Tension, however, is rarely fixed; rather players will have a tension with which they feel most comfortable but will continually tweak it depending on various factors including the court surface, altitude, temperature, game styles, and the condition of the balls. ‘My string tension is never constant,’ says Filip Peliwo, the 2012 Wimbledon, French Open and US Open Junior Champion. ‘I normally change it by a few pounds depending on the surface, temperature, stringer and machine. I also change it depending on how I am feeling at the time.’

Before the introduction of synthetic strings, almost all tennis rackets were strung with natural gut, made from the outer layer of sheep intestine. Natural gut continues to be used by many of the world’s leading players because it is extremely powerful and offers great feel on the ball, but it can be too powerful and also expensive in comparison to synthetic alternatives, so some players will opt for natural gut as part of a hybrid set-up. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

As the Bryan brothers mentioned, however, many players go beyond these basic adjustments and make changes to the racket frame itself. Much of Sampras’ serving power was attributed to the addition of four to five lead weights taped onto his racket, and today many professionals have the weight adjusted during the manufacturing process. James Allemby, a Barcelona-based touring professional, adds 18 g (0.6 oz) because it allows for ‘easier access to power,’ he explains. ‘It allows me to play looser knowing that the racket is helping me to generate pop on the ball.’ In comparison, with light rackets he finds that ‘a lot of the acceleration goes nowhere.’ Much of his reasoning comes down to his style of play: instead of coming to the net, James constructs the majority of his points from the baseline, and the added weight allows him to hit heavily from the back of the court without jeopardising his control and accuracy.

At the professional level where elite players go head-to-head, tournaments can be won and lost on minute details, so every player must have not only a racket that perfectly complements his or her playing style and strategy, but also an array of rackets fine-tuned to compensate for changes in temperature, temperament and ball condition.

Other changes to the frame involve the handle. The Bryans switched from Wilson to Prince but preferred the handle shape of the former. To get the best of both worlds they had Wilson-shaped handles moulded onto their Prince rackets. ‘This mould is applied to every frame we use so we always have a consistent feel,’ they say. Gonçalo Oliveira, now ranked number 426 in the world, replaces the original grips of his rackets with thinner over-grips because he finds them more comfortable. Players can also install vibration dampeners to reduce the vibration transferred up through the arm, and most players will also note a change in the ‘feel’ of the racket on contact. Even the butt cap, the thick part at the bottom of the handle, is more than mere decoration. Many players feel that a smaller butt cap increases a racket’s manoeuvrability; this is especially true amongst those who play with a single-handed backhand. By contrast, French player Richard Gasquet, who possesses one of the finest single-handed backhands in the game, builds up the size of his butt cap because he prefers the solidity it offers when changing from forehand to backhand and vice versa.

Many players install lead tape at various points on their racket frame in order to enhance their feel on the ball striking. The effect of the weight depends on where it is added. Looking at the racket face as a clock, players will add weights at three and nine o’clock to minimise frame-twisting on off-centre hits by pulling the sweet spot, the ideal place to strike the ball, out to the sides. On the other hand, weights at ten and two o’clock will raise the sweet spot and make shots hit high in the string bed feel more solid. Other players add weights at 12 o’clock to draw the sweet spot up the string bed without any substantial increase in the overall weight of the frame, while others add weights at six o’clock to increase the racket weight without reducing manoeuvrability. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

The final consideration for players when it comes to customisation is racket matching. It’s not uncommon for two theoretically identical rackets to feel different because manufacturers allow up to a 5% difference in various specifications. Though a fine margin, it is one that elite players cannot afford and so many of them will work with a specialist technician who will ensure that each and every racket is the same, and many of the game’s elite will even travel with a personal stringer in order to rule out any inevitable disparities that stem from minor differences in technique. Sampras, for example, employed professional stringer Nate Ferguson to travel with him to tournaments around the world.

It’s not uncommon for players to add weights to the handle of the racket with a view to increasing the manoeuvrability of the racket head. In addition to this, many players will change the size of the grip and the butt cap either by building it up with extra over-grip or filing it down. Some feel a smaller grip increases manoeuvrability and feeling on ball striking, while others enjoy the solidity of a large grip. (Photo: Tall Guy Pictures)

Racket customisation and modification is a fascinating and continually evolving world, and players keep their set-ups strictly confidential while always experimenting on the practice court in search of any small modification that will improve their play. Consequently, the technology and information available today have pushed the standards of the game to greater levels that few could have anticipated in the days of natural gut strings and heavy, wooden frames, and it’s exciting to see what further developments there will be in the future. Nonetheless, as profoundly creative and critical as this aspect of the game is, for those who watch from the outside it is easy to miss.