Gaming the Game

Throughout the history of sport, athletes have strived to find methods of gaining a competitive edge over opponents. In the endless quest for victory, ethics sometimes fall by the wayside.

Cover Photo: In the early years of the Tour de France, much of the race took place beyond the view of spectators and cameras, and cheating was widespread: riders getting lifts in cars or jumping on trains, fans dumping nails on the road or attacking riders, and substances of all kinds being abused. Above, Noël Amenc pushing his bike up to Col de Tourmalet in 1920. (Photo courtesy of Presse Sports)

It happened on a Sunday in the spring of 1994, during La Flèche Wallonne, one of Belgium’s many venerable cycling events. Despite the nasty weather, tens of thousands of spectators lined the streets, thousands of them standing alongside the last climb, only 1,300 m (4,300 ft) long, but with a punishingly steep grade. That year there were clear leaders: Moreno Argentin, Giorgio Furlan and Evgeni Berzin, all riders for the renowned team Gewiss-Ballan. Leaving all the other competitors lagging far behind, they looked like supermen, storming the climb as if they hadn’t already put hundreds of kilometres behind them, riding like machines. If they were machines, then they were machines fuelled by erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that boosts red blood cell production, increasing athletes’ oxygen intake and endurance. Team doctor Michele Ferrari had administered it in what are enormous doses by today’s standards, and it propelled them to an astounding victory. Of course, that 1994 Flèche Wallonne was neither the first nor the only incident in the history of sports doping, but it serves as a good illustration of how it works, of the ever more complex and creative game of cat and mouse between those who work to maintain fair play in the athletic world and those who seek to win at any cost.

For one thing, Gewiss-Ballan’s riders were using what was then a relatively new doping method. EPO had already been banned by the International Olympic Committee in 1985, but no test was developed and implemented until 15 years later. Part of the difficulty is that artificial EPO is difficult to distinguish from EPO produced naturally by the body, but another aspect is that EPO represents only one step in the endless search for a competitive edge, ethical or not, and the resulting effort to detect and eliminate unethical practices.

Athletes have a huge variety of doping substances at their disposal. There are steroids (to boost muscle growth), narcotics (to suppress pain), beta blockers (to slow the heart rate), and stimulants (to increase energy).

For as long as humans have competed, they have sought out ways to get and maintain advantages over their opponents. Historians record that Olympic athletes in Ancient Greece used mushrooms and herbal beverages to increase their strength and endurance. The word ‘doping’ itself can be traced back to 18th-century Africa, where Dutch colonists observed indigenous tribes using ‘dop’, an alcoholic beverage, as a stimulant in religious ceremonies and sports competitions, and adopted the word as a term for stimulant beverages in general. In more recent years doping has become far more sophisticated as medical science has advanced. The days of using drugs such as alcohol, ether, cocaine, heroin and strychnine are long past, and today’s more subtle techniques use substances like EPO, steroid precursors, human growth hormone and even transfusions of the athlete’s own previously stored red blood cells. The cutting edge, however, is gene doping, tweaking the athlete’s very genes to build muscle, increase speed and reduce recovery times. Whether or not gene doping is actually being used now is anyone’s guess, but the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has been studying it since 2002 in the hope of being able to detect and punish it.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Dopers, of course, are just as determined to find ways to evade testing or, better still, to test negative to ‘prove’ that they are clean, and the Gewiss-Ballan team probably passed doping tests (which had been introduced at the Tour de France, not without controversy, decades earlier in 1966). EPO was new enough that it went undetected. Riders using less sophisticated doping, either for lack of information or lack of finances, had to find other ways to pass the test, and were certainly aware of Michel Pollentier’s infamous attempt at the 1978 Tour de France. He had attempted to pass a drug test by taping a condom filled with foreign urine under his arm and running a tube under his shirt and through his shorts, but was caught by a doctor. Today a more modern athlete might be tempted to try the Whizzinator, an easily obtainable prosthetic penis sold with synthetic urine and a heater pack to keep the urine at body temperature. Or to use a catheter to inject clean urine into his bladder before the test.

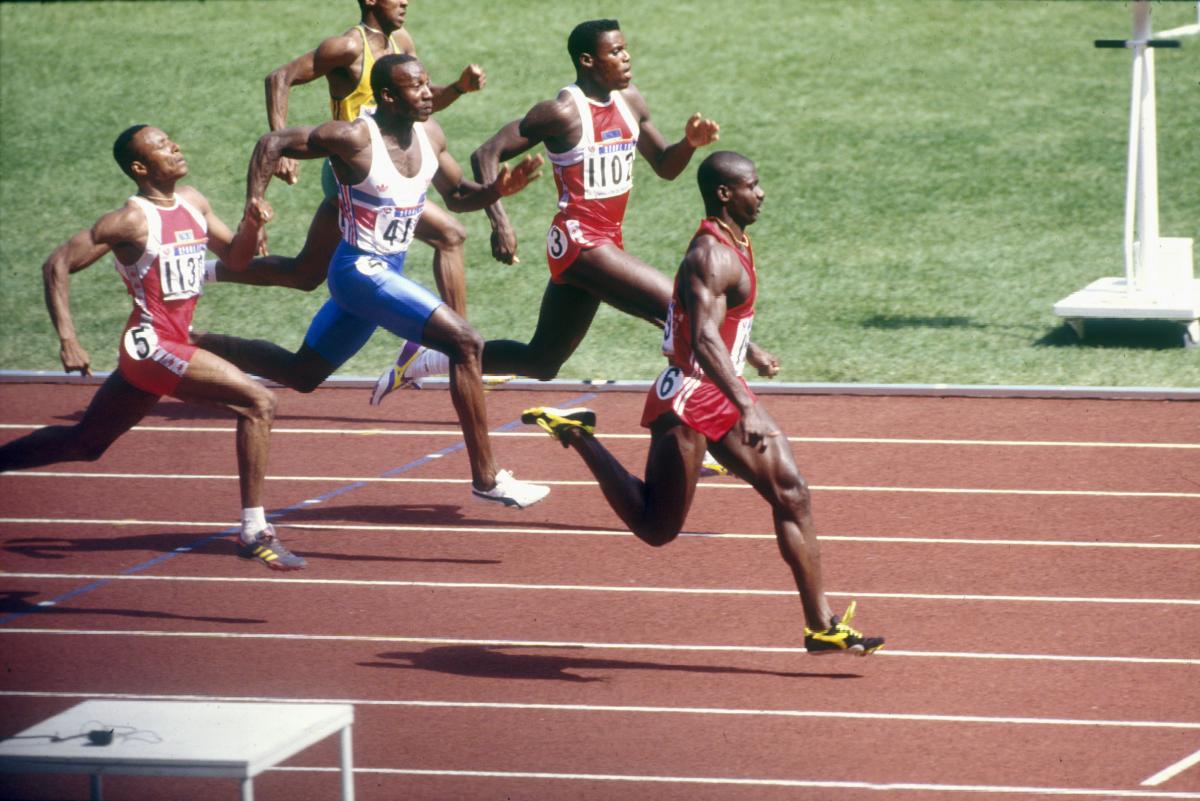

Ben Johnson winning the Men’s 100 Metres at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, sometimes called ‘the dirtiest race in history’. Two days later, Johnson was stripped of his gold medal after testing positive for the use of steroids. Six of the eight finalists were found guilty of using performance-enhancing or other illegal drugs at some point in their careers. (Photo: Legros Lecoq, Presse Sports)

Or if the test cannot be avoided, then perhaps it can be fooled. In the case of blood tests for EPO, for example, saline injected into the bloodstream can dilute haemoglobin and haematocrit concentrations to below official thresholds if administered as little as 20 minutes before a test. Urine tests have also been spoofed: common household soaps contain protease, an enzyme that breaks down EPO, and athletes have been known to rub it on their hands and urinate over their fingers, or if they suspect that they will be asked to wash their hands before providing the sample, to hide it under their foreskins.

For those who prefer not to tinker with their body chemistry, either because of the side effects of doping or the risk of being caught, there are other ways to cheat. Accusations of ‘mechanical doping’ go back to Fabian Cancellara’s victory in the 2010 Tour of Flanders, but Belgian cyclist Femke van den Driessche became the first rider in history to face sanctions because of a bicycle fitted with the Vivax Assist system, an electric motor concealed in the seat tube. Italian newspaper Gazetto dello Sport reported on a far more sophisticated electromagnetic boost system using wires embedded in a carbon-fibre wheel, allegedly in use at the highest levels of the sport. Those who choose the medical route, however, have to master not only their training and competing, but the art of evading tests. Cheating, as they say, is easy, but winning and not getting caught is hard.

The winners’ podium of the Tour de France 2005 with Lance Armstrong (centre), Ivan Basso (left) and Jan Ullrich (right). Armstrong was disqualified in 2012 by USADA (the United States Anti-Doping Agency), Ullrich was officially stripped of his finish by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, and Basso was found guilty of doping several times, just like all but one of the top ten finishers of that year’s Tour. (Photo courtesy of Presse Sports.)

One such master was Lance Armstrong, who used EPO up until 2001, knowing that it was undetectable. He used blood doping and HGH up until 2005, knowing that they were undetectable. He was very precise when it came to the timing of injections the night before the race, and he used a wide range of masking agents to cover his tracks. This level of information, however, goes far beyond what an athlete or trainer can obtain without consulting a medical professional, and just as Gewiss-Ballan had Michele Ferrari, nicknamed ‘Dottore EPO’, athletes and teams turn today to clinics like Victor Conte’s Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (most infamously associated with Barry Bonds, Tim Montgomery and Marion Jones) or Biogenesis (linked to Alex Rodriguez and 12 other Major League Baseball players). Like Conte, who returned to the sports-supplements industry after serving a total of four months’ prison time, Ferrari continued to have close relationships with cyclists after being fired by Gewiss-Ballan, among them Lance Armstrong, who based his doping system on Ferrari’s.

The Festina cycling team at the start of the Tour de France in 1998. All members of the Tour team were arrested and ejected from the race after its director admitted a systematic programme of administering performance-enhancing drugs to riders. (Photo: Clement, Presse Sports)

The doctors are among the most colourful characters in the doping world. Conte was a bass guitarist before he began to manufacture supplements, even playing with the legendary Tower of Power from 1976 to 1979. Ferrari once boasted in an interview with a local newspaper that his name appeared 450 times in the USADA’s report, while Armstrong’s name only appeared 200 times. Nor was Ferrari content merely to advise the cyclist on drugs, recovery times and test evasion; he also discussed raising the bike saddle by 2 mm (0.08 in) or adding another training session. He owned an apartment in the Swiss mountain village of St Moritz, where he received athletes from all over the world—cyclists, football players, tennis players, boxers, cross-country skiers—who came not only to train at high altitudes, as they told everyone, but also to receive doping substances. And when important cycling races were taking place, he sat at home in front of his television, pleased as any child in front of a Christmas tree when one of his riders won.

Even after his lifetime ban by USADA in 2012 and Armstrong’s fall from grace in 2013, Ferrari continues to move in elite sports circles, offering his services as a coach to anyone who wants to hire him. And this is perhaps the most troubling and complicated way in which the scene from the 1994 Flèche Wallonne serves as a microcosm of sports doping: athletes and coaches hungry for victories and trophies, doctors hungry for fame and influence, sponsors eager for a return on their investment, and fans willing to wait in the rain for the thrill of watching a superhuman performance may all be willing to turn a blind eye to doping’s existence. In fact, some of the earliest cheating at the Tour de France was committed not by cyclists, but by spectators throwing rocks, nails or broken glass in front of riders they didn’t like. The cases of East Germany’s State Plan 14.25 and the Russian scandal at Sochi demonstrate that a willingness to not only ignore but also to facilitate programmatic doping extends to the level of the state.

Michele Ferrari, the team doctor for the Gewiss–Ballan road bicycle racing team, and the mastermind behind the doping methods of dozens of cycling professionals, supervising their use of blood transfusions, EPO, testosterone and other banned substances. (Photo: Biville, Presse Sports)

The end result of all of this is that everything we know about doping may be only the tip of the iceberg. A study by researchers at the University of Adelaide suggests that on average, the chance of successfully detecting doping is around 2.9% per test. French gene-therapy researcher Dr Philippe Moullier, who was able to boost EPO production in lab animals, has had to explain to countless athletes that his technique can have unpredictable, potentially fatal side effects. ‘They didn't seem to care, it didn't seem to be a problem for them,’ he says. ‘The competition is so high, those guys are ready to do anything to make the difference.’ Even the widely touted ‘biological passport’, which seeks to demonstrate doping use indirectly by monitoring athletes’ biochemical profiles, has been successfully challenged in court as insufficiently sophisticated. The dopers are amongst us, and they always will be. From time to time we may catch a glimpse of one of them, but most of the time their ruthless and somehow subversive activity stays undetected. How many more like Ferrari and Conte are out there?