Designing Strategy

The stereotype of the ‘dumb jock’, gifted more with muscle than with intelligence, overlooks the importance of strategy in sports, of creativity that can give brains an edge over brawn.

Cover Photo: Two variations of the same passing play from Vince Tobin’s 1998 Arizona Cardinals playbook. Tobin would call this play through his headset, and the quarterback, Jake Plummer, would choose which version to run at the line of scrimmage. The ’98 Cardinals would squeak into the playoffs, but Tobin only lasted five seasons as a head coach in the NFL.

In the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, far from the dignified bronze busts of the inductees, far from the victors’ rings and game-worn jerseys, far, far away from the gleaming Vince Lombardi championship trophy, is a wristband once worn by halfback Tom Matte. Matte himself is not an inductee, nor will he ever be, and he only wore the band for three games in 1965 when he stepped in as emergency quarterback for the Baltimore Colts to cover for injured teammates. Since there was no time for Matte to memorise all the plays that he would have to call, legendary coach Don Shula devised an unprecedented shortcut: a wristband with a simplified version of the Colts’ offence written on it. The wristband itself is modest, an index card mounted on a strip of dull, brown vinyl, but it helped Matte lead the Colts to victory against the Los Angeles Rams, and it is a seminal artefact in NFL playbook design and implementation. Today, 50 years later, nearly every NFL quarterback wears one.

Philadelphia Eagles head coach Doug Pederson (second from left) coordinates with the other coaches during an NFL game against the Detroit Lions. Nowadays, NFL coaches often select plays by committee. Most teams employ several sideline coaches as well as analysts and coordinators who monitor real-time video data and relay suggestions to the coaching staff. (Photo: Jorge Lemus, Picture-Alliance/NurPhoto)

Matte’s wristband illustrates one fundamental fact of sports, that muscle and brute force can be trumped by strategy and creativity. If the thrill of sports is in the beauty of human beings pushing themselves to their physical limits, then the purpose of intelligent play design is to minimise the role of the physical contest or, if possible, to remove it altogether. It creates a moment of optimal solitude, an O breaking free from the crowd of Xs on the whiteboard: the football player who goes untackled or the basketball player who is open. Strength allows athletes to overpower a defence; design allows them to ignore it. They must not only play faster, stronger, or harder, but also smarter.

Boston Celtics coach Doc Rivers instructs forward Mikki Moore during the NBA game against the Los Angeles Clippers. (Photo courtesy of Picture-Alliance/Newscom.)

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.This is true even at the ground level, where young players are drilled in the fundamentals of their game. Liam Flaherty and Nat Rubin, high school basketball coaches at Saint Ann’s School in New York City, know this well. Saint Ann’s is primarily an arts school, famous for turning out poets, actors, filmmakers and architects rather than high-quality athletes. Does any of the artistic training these kids get bleed over into the play design? Flaherty and Rubin are cheerfully blunt. ‘At this level, one kid is still better than all the rest. So on defence, we want to keep it simple because our players are sometimes scared to go man-to-man. We don’t use the “triangle”, the “West Coast offence”, the “spread”, or anything like that. At this level it’s about being big and teaching confidence.’ Their basic, utilitarian strategy (three Xs in front, two in back) lets their players avoid the physical mismatches they are so wary of, perhaps preserving the good looks of a future film star, but it is also flexible enough to allow for some adaptation (two Xs in back, three in front) during a game.

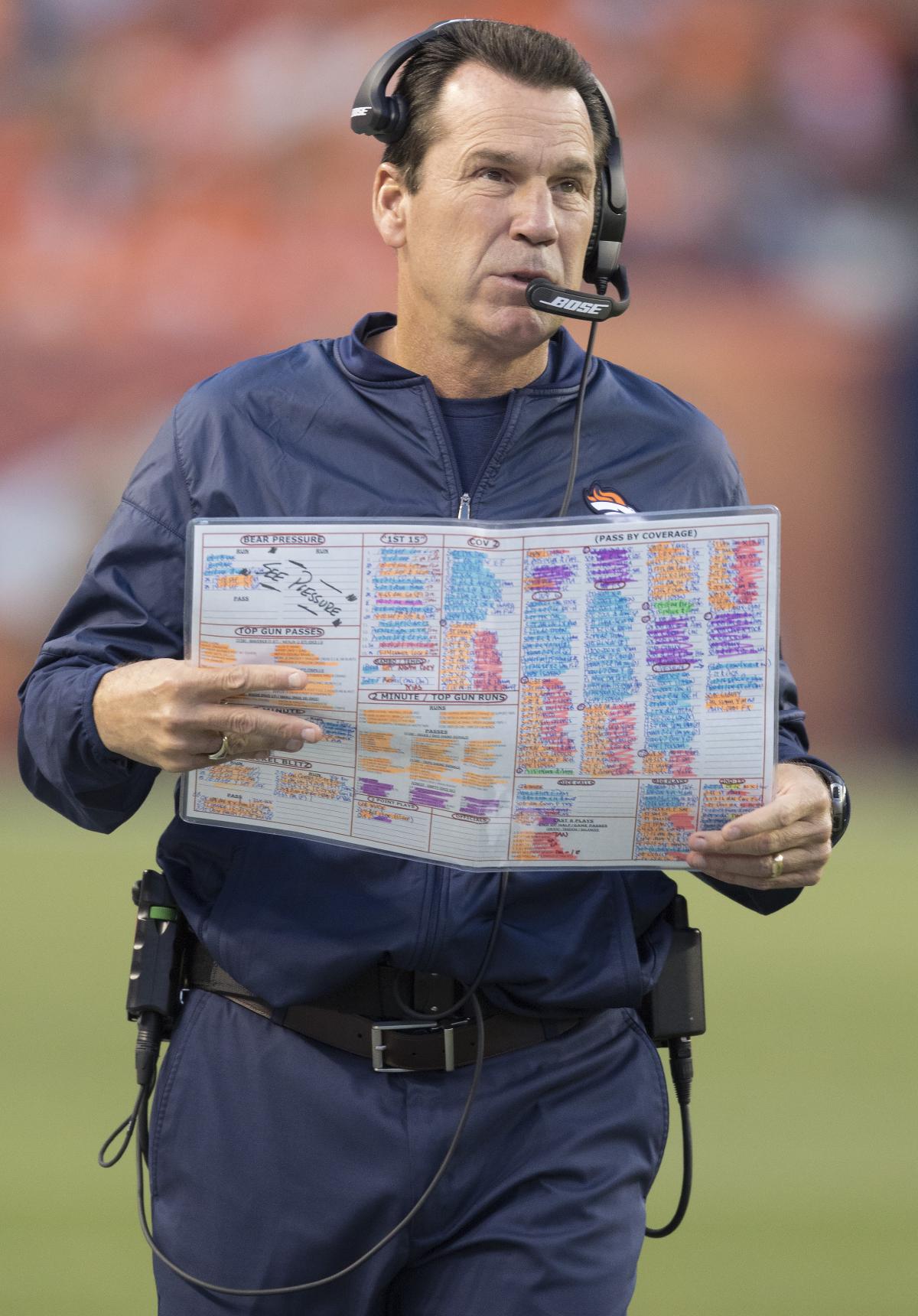

Denver Broncos head coach Gary Kubiak practising a play-calling system during a pre-season game. In any football play, each of the team’s 11 players on offence has a specific, scripted task. (Photo: Gary C. Caskey, Picture-Alliance/Newscom)

College athletics are massive in the United States (across all sports, it is a roughly US$12.4 billion/€11.7 billion industry), and it is hardly surprising that the triangle offence sprang from one of these programmes, where coaches are allowed the freedom to experiment, rather than in the do-or-die environment of the professional leagues.

If high school basketball is the classroom where pupils learn to colour inside the lines, college basketball is the design studio where innovation is unleashed, one step above the relentless drilling of fundamental patterns of the game, one step below the cutthroat win-now-or-be-fired atmosphere that discourages professional league coaches from experimenting too much. The triangle offence of which Flaherty and Rubin spoke is a perfect case in point, a strategy that turns conventional basketball wisdom on its head. Whereas Matte’s wristband contained a limited number of set strategies designed to penetrate a defence, the triangle offence employs a multiplex stack of ‘automatics’, meticulously rehearsed contingency plans that enable a team to react instantaneously to events as they play out on the court. Its flexibility relies on a virtual interchangeability of players, requiring intensive teamwork built on continuity over multiple seasons, and it has both its staunch adherents and vocal critics. Doug Eberhardt, a former player and coach currently working as a sports analyst for GlobalTV BC, is one of the former. He says, ‘I know it’s the oldest cliché that basketball is like free form jazz, but… they’re always moving and moving the ball. It’s beautiful, it’s like organised chaos.’ Eberhardt is a basketball obsessive and confesses to watching games with slips of paper in front of him—‘just in case a coach runs something that I find visually appealing’—so he can jot down the movements and formations and add them to the inventory of plays he keeps sealed in a Rubbermaid container. ‘If you’re a fan of design, simple design, the triangle can be spectacular to watch,’ he says. ‘Because A happens here, then B happens here, and it’s all done in a very geometric way.’

Even though coach Bill Belichick can communicate with quarterback Tom Brady through a helmet microphone, raucous opposition fan noise can sometimes make in-person clarification necessary. (Photo: John Angelillo, Picture-Alliance/Newscom)

The triangle is also so successful because it breaks the mould of what basketball players have been trained their whole lives to do. ‘Player and coaches have grown up running and designing plays that force the defence to react, not the other way around,’ Eberhardt writes. ‘In both its insistence on patience and the way it inverts the traditional relationship between offence and defence, the triangle is counterintuitive. This is a big part of why it works, when it works. It is also why making it work can be so difficult.’ In order to learn it, offences have to reprogramme themselves, not an easy task. Nor are basketball players alone in this. University of South Carolina quarterbacks coach Kurt Roper also knows the difficulties of getting professional athletes to acquire a new way of thinking: ‘Learning a new offence is like learning a new language. The players understand football… But it’s like they’re thinking in English, and we’re teaching them in a foreign language. Our job is to get them to think in our language.’

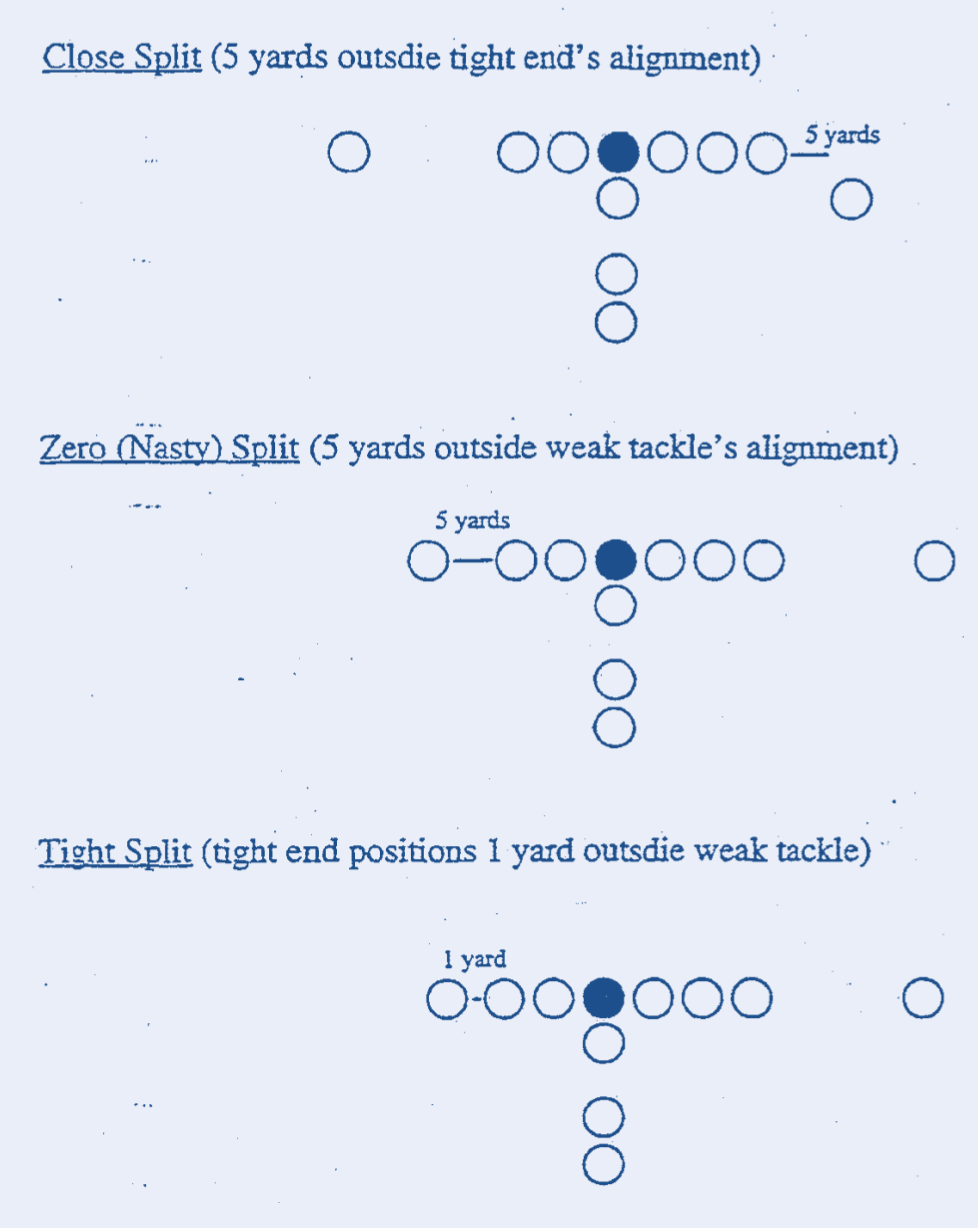

Three possible locations of the tight end in the ‘I Formation’ in the 2000 St. Louis Rams playbook. After winning the 1999 Super Bowl with the Rams, head coach Dick Vermeil announced his retirement. Martz, his successor, tried to run his 3-digit offence for a second year, but he was never quite as successful; the ’00 Rams crashed out in the playoffs.

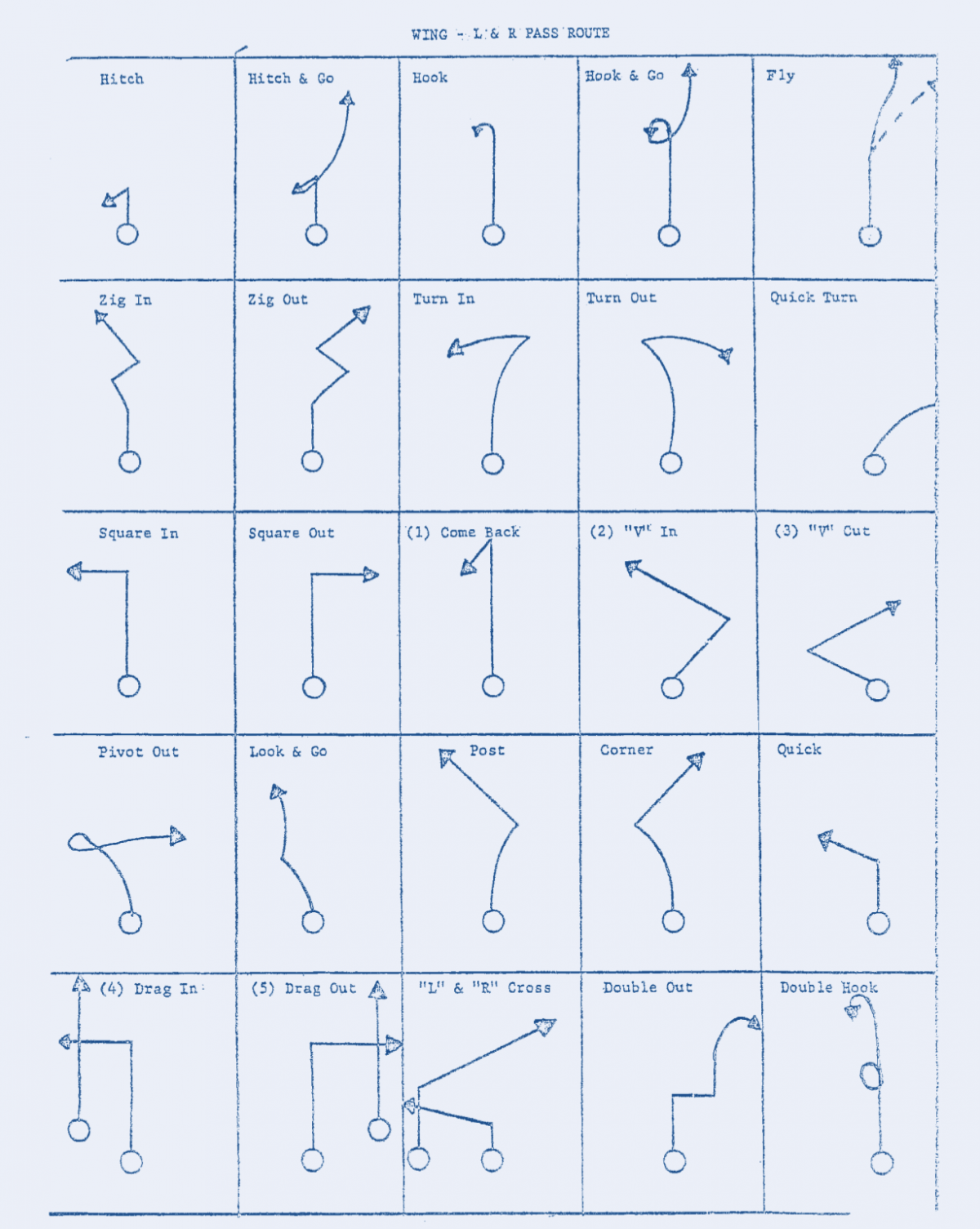

Wide receiver routes from head coach Vince Lombardi’s 1966 Green Bay Packers playbook. The 1966 Packers were the first team to win the Super Bowl, and Lombardi would have made all of his quarterbacks and receivers memorise these routes. Then, in the huddle, quarterback Bart Starr would call the specific play from the pages and pages of information the team had memorised.

In either or perhaps any sport, however, the end goal of such change is the same: to conceive, develop and execute a strategy that will maximise the athletes’ physical assets by deploying them in innovative ways. Truly groundbreaking play design may even transcend individual athletes and personalities, just as the triangle offence emphasises team play over individual superstars. This is why an unheralded and unknown St. Louis Rams team was able to win the 1999 Super Bowl by running the high-octane ‘3-digit system’ in an ascent so sudden and unexpected that when Sports Illustrated ran a cover story on their quarterback, Kurt Warner, they used the title ‘Who IS this guy?’. Whether it’s maximising a spread system to allow a team of nobodies to win the Super Bowl or drawing up a zone so outmatched art students can defend properly against their larger and taller peers, the fundamental idea remains the same: use the playbook to transcend the physical. In the end, this is precisely why Tom Matte is not in the hall of fame, but his wristband is. Millions of aspiring players can throw a football, but not every object can change the game’s design.