Little Ambassadors of the Country

How a land where so much is governed by tradition became known (at least to stamp collectors) as a country of wildly groundbreaking innovation.

Cover Photo: Perhaps no other Bhutanese stamp has received as much attention as the so-called talking stamps. Issued in 1972 as a set of seven, talking stamps were miniature, one-sided vinyl records that had adhesive backs so that they could be affixed to letters, but also played on a standard turntable. The stamps featured audio recordings of folk songs, the national anthem, the history of Bhutan in its national language, and the history of Bhutan as narrated in English by Burt Kerr Todd himself. (Image courtesy of the Peter Biľak collection.)

Practically speaking, a postage stamp is a small piece of printed paper with a layer of glue on the back. There is nothing intrinsically valuable about it. Its price represents partly the cost of production, and partly the markup imposed by the government that funds the postal delivery. Theoretically, the stamp’s production should be as cheap as possible so that the bulk of its price goes towards the service rendered, but since collecting these tiny bits of paper is one of the world’s most popular hobbies, with collectors willing to spend small fortunes on the never-ending stream of new stamps, there is a market for innovative (and more expensive to produce) postage stamps.

Bhutan launched its postal system in 1962, opening its first post office in Phuentsholing, a small town on the Indian border, and producing its first postage stamps. Bhutan also opened its first paved road in the same year, clearly demonstrating its desire to open the hermit country to the world beyond. Although ambitious infrastructure and modernisation programmes, formulated by the country’s first five-year plan, were set up, funds to realise them were lacking.

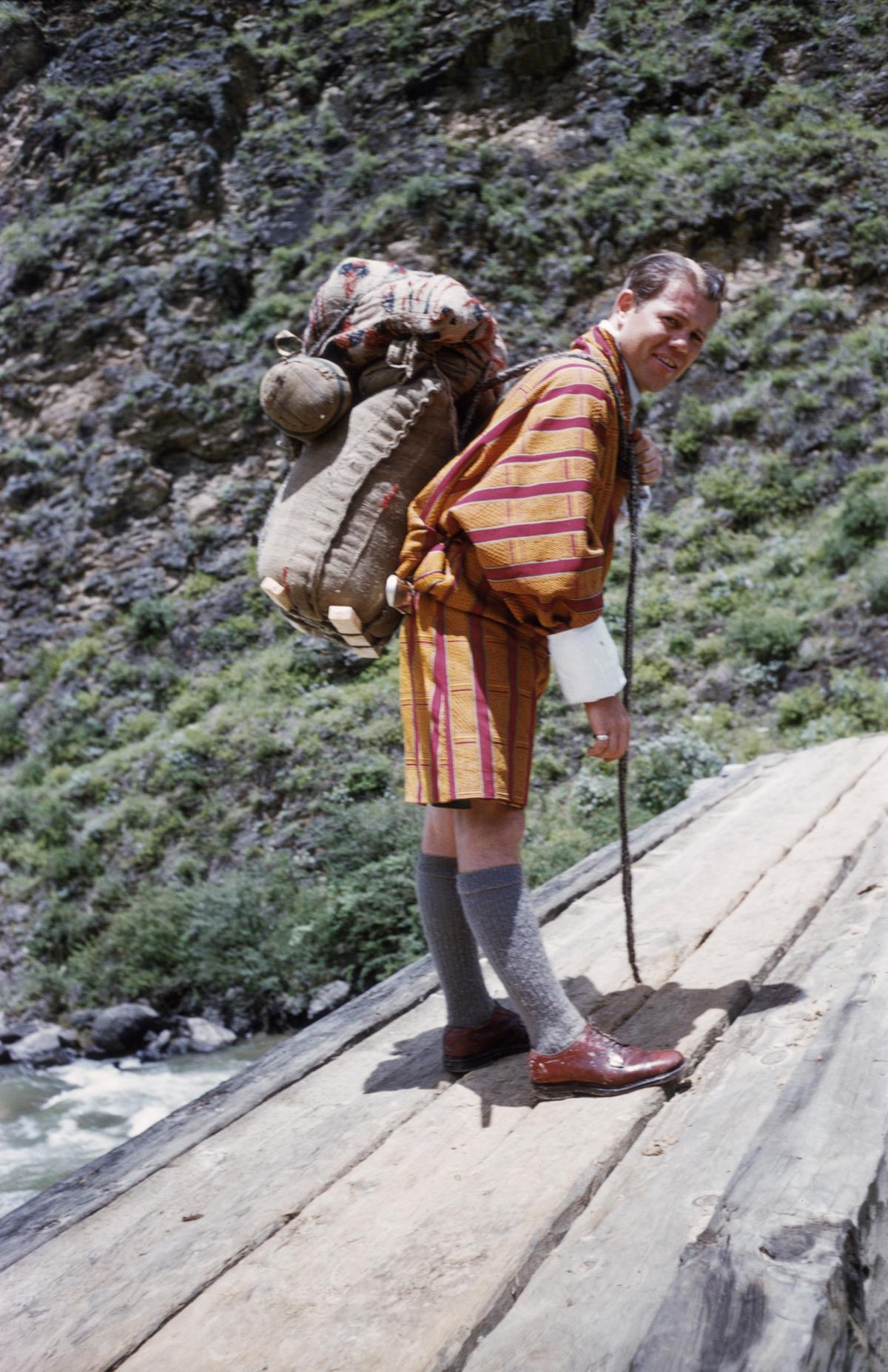

Burt Kerr Todd was probably the first American to visit Bhutan in 1951 and later introduced postage stamps to Bhutan. While in graduate school at Oxford he met the future queen of Bhutan, and he maintained contact with the royal family throughout his life. (Image courtesy of Burt Todd family archive)

The Bhutanese government applied to the World Bank for a US$10-million (US$81.32M/€73.84M in today’s money) loan to help finance its infrastructure, including hospitals, roads and an airfield, but was rejected. One of the advisors who had drafted the application was Burt Kerr Todd, a wealthy American entrepreneur and a personal friend of the Bhutanese royal family. In the aftermath of the rejection, Todd spoke to a high-ranking official who had attended the talks, suggesting an alternative fundraising method: issuing postage stamps. In comparison with a multimillion-dollar loan, this may seem like an odd move, but Todd recognised that stamp collectors could indeed be an important source of income for smaller countries who created limited runs of attractive stamps designed mainly to be bought by collectors.

Ever the maverick businessman, Todd suggested setting up the Bhutan Stamp Agency, a private company established in the Bahamas, which would produce the stamps and handle their sale on the international market. Up to this point, the Bhutan government hadn’t issued stamps and was sceptical of their ability to raise significant revenue, but it agreed to the project for different reasons. As a tiny nation sandwiched between the world’s two most populous countries, China and India, both of which had a history of annexing neighbouring Himalayan kingdoms, Bhutan saw an opportunity to assert itself as a sovereign state. Even if the stamps failed to generate substantial funding, they could help to build awareness of the country, raising at least political capital.

Todd’s first stamps were a failure. Just as Bhutan was largely unknown in the global community, its stamps were largely ignored by the philatelic market. More importantly, however, stamp collectors rely on a closed system of philatelic trade channels and on specialised journals. As a newcomer, Todd had no access to these channels, but over time he sought and received the advice of insiders who told him that to get the attention of the philatelists, the stamps would have to be highly attractive, playing to philately’s existing conventions.

After five years Bhutan Stamp Agency finally had its first major success. After exhaustive tests and years of development, a Japanese company hired by Todd was able to produce the world’s first three-dimensional lenticular stamps. This 1967 series, which featured images of astronauts and lunar modules, created a philatelic sensation. (Ironically, most Bhutanese had never watched a space launch, since Bhutan didn’t introduce television broadcasting until 1999, the last country in the world to do so.)

The 3-D stamps were denounced as gimmicks by philatelists, but captured the imagination of casual collectors. Market-savvy Todd set up giveaway programmes in US supermarkets, where consumers earned Bhutanese stamps with the purchase of groceries.

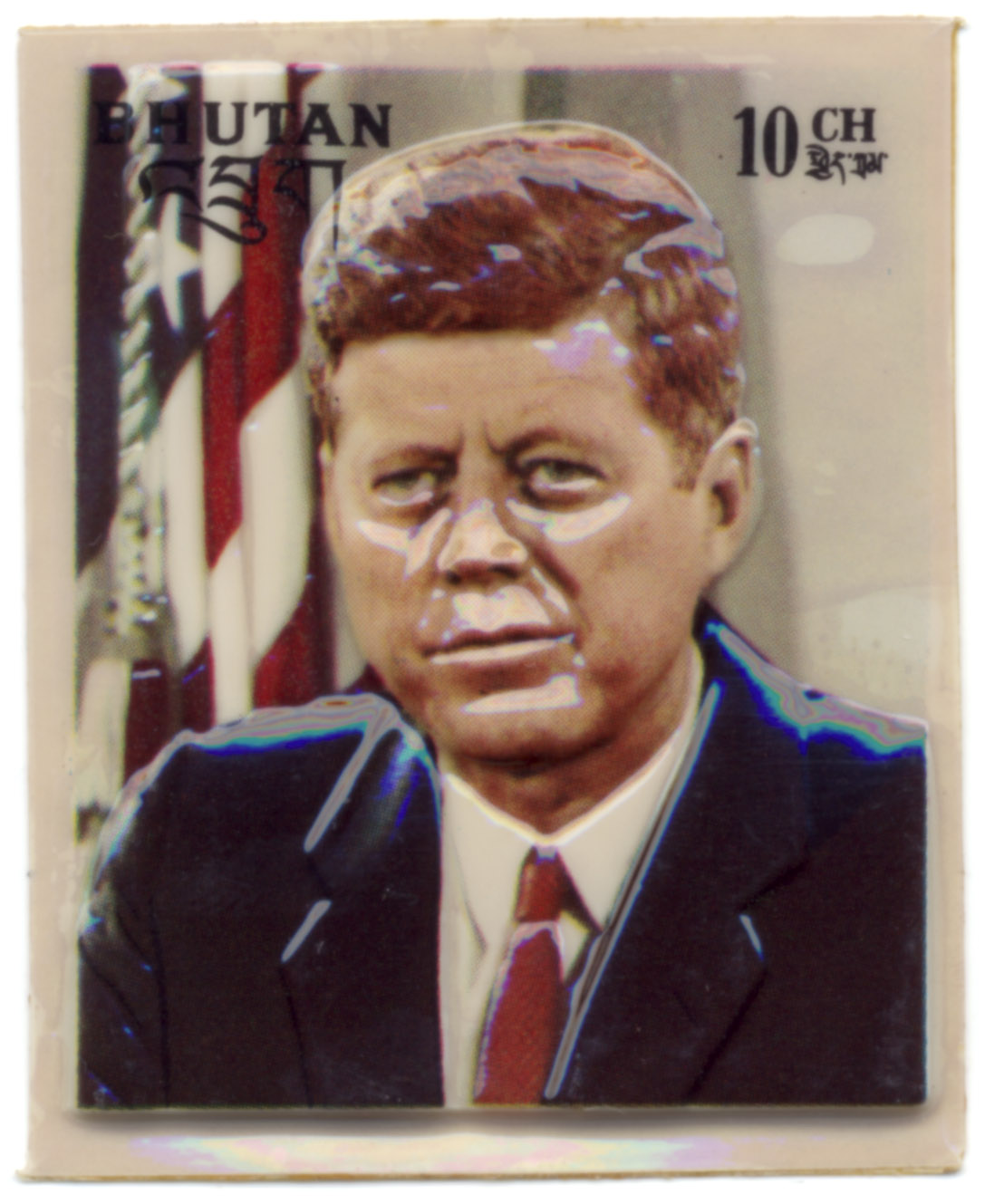

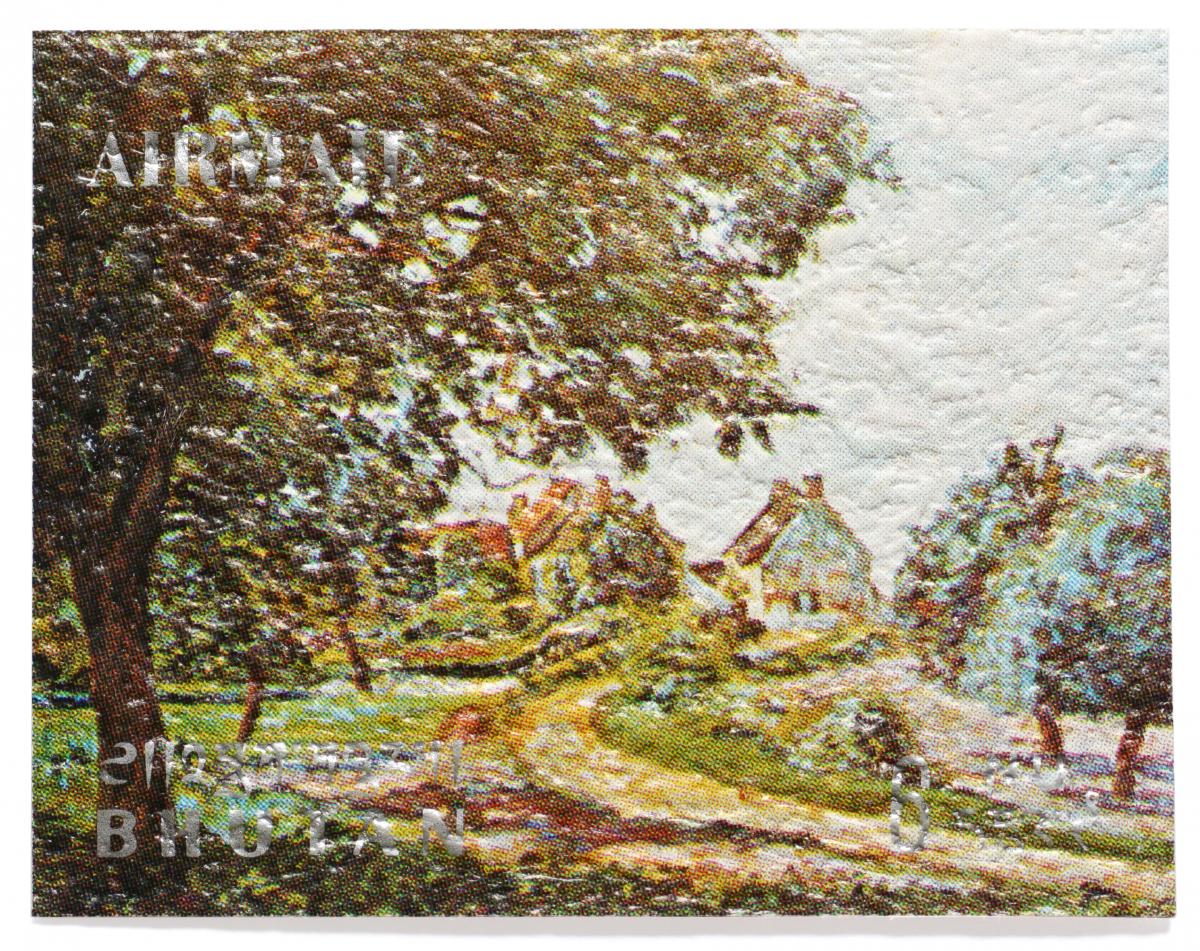

Nor was this the last of Bhutan’s unusual and innovative stamps. After the world’s first 3-D stamp came the first scented stamp. The first textured brushstroke stamp. The first bas-relief stamp. The first stamp printed on metal. The first on silk. The first on extruded plastic. By 1973, Bhutan’s greatest source of revenue was its stamps. The stamps functioned as Bhutan’s little ambassadors or at least cultural attachés, as Bhutan has a very limited number of diplomatic missions abroad, at present just five permanent embassies.

Stamps from Burt Kerr Todd’s first series of Bhutanese postage stamps, released on October 10, 1962. These are the only stamps ever to show Bhutan’s neighbour Sikkim as an independent state. (It was annexed by India in 1975.) When Bhutan produced its first airmail stamp, the country didn’t even have an airport. To this day, postal service in some areas of the country is provided by letter carriers who hike barefoot through the forest for days to reach remote villages. (Image courtesy of Peter Biľak)

A series of philatelic firsts: circular coin stamps made of foil (1966); 3D stamps (1967); silk stamps (1969); and CD-ROM stamp (2008). Todd hired artists and had stamps manufactured in China, Japan, Indonesia, Spain and Italy. (Courtesy of Peter Bilak.)

Perhaps no other Bhutanese postage stamp has received as much attention as the so-called talking stamps. Issued in 1972 as a set of seven in red, yellow, green, blue, purple, white and black, and in two sizes, the talking stamps were miniature one-sided vinyl records with adhesive backs so that they could be affixed to letters, but also played on a standard turntable. The stamps featured audio recordings of folk songs, the national anthem, the history of Bhutan in Bhutanese and the history of Bhutan as narrated in English by Burt Kerr Todd himself. The stamps came with a first-date cover envelope, and an explanation:

This envelope contains your Bhutan postage stamp. In order to develop a national economy, these unusual beautiful stamps are now the principal industry. Bhutan is a tiny 90 mi. kingdom high in the Himalayan mountains. This stamp, one of a series, is a collector’s item.

As intended, this oddity appealed to postage stamp collectors worldwide. Today a single talking stamp can sell for hundreds of euros.

First extruded plastic stamp, 1972

In 1974, two years after the death of the third King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, a friend of Todd, the contract with the Bhutan Stamp Agency was cancelled. The Bhutanese Department of Posts and Telegraphs appointed the Inter-Governmental Philatelic Corporation (IGPC), a New York-based company representing many small and developing countries in the designing, production and marketing of postage stamps. IGPC continued to develop high face-value stamps with no local postal usage with themes appealing to international markets unrelated to Bhutan. Some of the IGPC stamps for example featured themes such as the Olympic Games, or the popular Disney characters Goofy, Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck, who were virtually unknown in Bhutan at the time.

In 1996 the Bhutan Postal Corporation was established as an autonomous organisation whose chairperson is the Minister of Information and Communications. Apart from providing domestic and international postal services, it also produces and markets stamps. Although IGPC still lists Bhutan as one of its clients, Karma Wangdi, CEO of the Bhutan Postal Corporation, informed us that Bhutan produces its stamps exclusively on its own.

Today Bhutan Post designs all its own postage stamps in-house, but prints them abroad, usually in an edition of about 10,000 pieces. The themes are proposed by a Bhutanese advisory committee, balancing national interests with international appeal. Ninety per cent of the produced stamps are for philately purposes, the rest for domestic use to send letters and postcards.

Tashi Wangchuck is Bhutan’s sole stamp designer at present. He is a busy man, designing about 14 series of stamps a year. With no graphic design courses offered in the country, Wangchuck picked up basic art and design techniques on the Internet. Today he is responsible for researching the stamps, producing the artwork and overseeing production.

The global philately market is declining, not only because email and text messages are increasingly replacing traditional letter-writing, but also because the number of young collectors is declining too, raising concerns for the future of the once-popular pastime. Bhutan, however, seems not to be affected by those trends, and Bhutan Post plans to increase the print runs of its stamps to about 30,000 pieces, working with their agents abroad to market them. Most of the agents are in the neighbouring countries India and China, whose markets are expanding even as the European and North American markets decline.

The stamps illustrating this article were purchased from one of Bhutan Post’s agents, Mukul Bhowmik in West Bengal. Mr Bhowmik became interested in Bhutan’s postage stamps when he encountered the stamps produced by Todd’s Bhutan Stamp Agency, some of which were produced at India Security Press in Nashik. As an authorised stamp dealer Mr Bhowmik receives his quota of each newly produced stamp series, and usually has no difficulty selling them.

First textured brushstroke stamps, 1968

While Bhutan Post generated a profit of 8 million ngultrum (€108,500 or US$74,210) in 2008, in 2015 that figure was already 13 million (€176,300 or US$196,600), thanks to its new philately website. ‘With the e-commerce site we should be able to make a huge jump in numbers; at least that’s what we are hoping for,’ says Wangdi. At the same time he is adamant that Bhutan Post chiefly represents national interests: ‘We cannot be completely market-driven. Our stamps are still our ambassadors, so from that perspective, we cannot just cover what the market wants. We are very conscious of what we produce and what we send out to the market. Everything that we do, even in philately, is governed by the Gross National Happiness philosophy and our culture.’

Many things have changed in Bhutan, but stamps continue to play an important role. The newly opened postal museum in Thimphu is now a major attraction. At the museum shop, tourists are not only able to purchase Bhutanese stamps, but can also produce personalised stamps featuring their portraits set against one of Bhutan’s historic fortresses or temples, or even using photos from their own USB drives. Museum exhibits include a sculpture of Ugyen Tenzin, one of the last postal runners who retired in 2010 at the age of 56. Postal runners, people trekking off-road routes to remote areas, are also the subject matter of several stamps, and were honoured in a 2004 documentary movie by Ugyen Wangdi Price of Letter capturing Tenzin’s life and work.

The headquarters of the Bhutan Postal Corporation in Thimphu is also a regular post office and the office of the Philately Division, where stamps are produced, as well as a postal museum. (Photo: Peter Biľak)

Even today, sending a letter to Bhutan’s Lingzhi region means that someone has to carry it on foot. The domestic postage rate for a letter is 20 ngultrum (€0.27 or US$0.30), and the journey includes crossing torrential rivers and camping in dense forests. Dorji Rhinzen, a son of Ugyen Tenzin, is also a postal runner. Speaking Dzongka through an interpreter, Dorji tells us about the five-day treks to Lingzhi that he makes once a month to serve 70 households that rely on him to bring official and personal letters. Lingzhi, a wild and mountainous region above the tree line, is outside of Bhutan’s electric grid system, but people use solar power and mobile Internet. In the summer he brings about 10 kg (22 lb) of post on every trip, while during the winter when there is no school, the load is smaller. Dorji doesn’t know of any other postal runners and may be the country’s last.

In 2008 Bhutan Post released CD-ROM postage stamps, another world first, as part of Bhutan’s commemoration of the 100th anniversary of its monarchy. The small-format disc contains video documentaries of events from Bhutan’s history: the anniversary of the monarchy, the coronation of the Fifth King, and the signing of the new Constitution. The CD-ROM postage stamps were issued in partnership with Creative Products International, a Pittsburgh-based company headed by Frances Todd Stewart, the daughter of Burt Todd. ‘The CD-ROM was actually my dad’s idea,’ Stewart explained. ‘He never used computers, but knew about CD-ROMs, and thought it would be a natural development to make a digital version of the talking stamp.’

According to Tashi Wangchuck, Bhutan’s sole stamp designer, this 2013 stamp series featuring traditional phallic symbols (considered effective in warding off evil spirits) is currently the top seller.

On the last day of our trip to Bhutan, I stopped by the headquarters of the Bhutan Post Office in Thimphu to buy the newest edition of the CD-ROM stamp, only to find designer Tashi Wangchuck behind the counter. I asked him what he was doing there, and he sheepishly replied that he likes to observe which stamps are popular amongst the tourists, taking cues for future series. (Phallus stamps were very popular, as well as stamps depicting monasteries.)

Hydropower export and tourism have become the country’s most profitable source of income, but stamps continue to play their dual role, generating much-needed revenue to fund Bhutan’s development, and also presenting the country to the outside world.