Drones And Phones

In a country where medical budgets and healthcare staff are stretched dangerously thin, telemedicine could help make the most of limited resources. As they wait for funding for more ambitious projects, Bhutan’s doctors are improvising their own home-grown solutions.

Cover Photo: The main road between Bhutan’s two major cities, the former capital Punakha and present capital Thimphu. Although the distance is only 72 km (45 mi) and traffic is light, the average speed is just 24 kph (15 mph) due to poor road conditions. In the summer, the monsoon brings heavy rains, landslips and falling rocks, while in the winter, snow and gale-force winds render high altitude mountain passes inaccessible. (Photo: Peter Biľak)

Bhutan is held together by a single, vital thread. Spooled out between Himalayan peaks, the winding East–West Highway ties Trashigang in the far east to Thimphu in the west, then runs south to Phuentsholing on the Indian border. Almost all imports—diesel fuel, toilet paper, steel nails, cooking oil—arrive along this route, borne by eight-tonne lorries sputtering black exhaust fumes. The lorries move slowly: carved into the mountainside, cracked by cold winters and soaked by the summer rains, the highway’s crumbling surface is a thin, broken strip of potholes, mud and rubble less than three metres wide. Every year, the road claims lives, but though many of its victims are killed in collisions, landslides and precipitous falls, others are not involved in accidents at all. They die in the backs of ambulances, from infections, trauma, or acute appendicitis.

Paramedics know that delivering a severely injured patient to surgery in less than 60 minutes, the ‘golden hour’, can make the difference between life and death. But in Bhutan, the only staffed operating theatre is in Thimphu, and for patients who have to cross the central highlands to get there, the journey does not take one hour: it takes two full days.

‘The biggest challenge in Bhutan is the landscape,’ says Dr Kinzang P. Tshering, president of Thimphu’s Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Services of Bhutan. Founded in 2013, his university is tasked with training specialists so that they can be available throughout the country instead of only in the capital. ‘So many cases require referral to Thimphu,’ he says. ‘Advanced infections, cancer, small babies with complications… there are so many issues where we have to transfer patients from east to west, over seven mountain passes.’

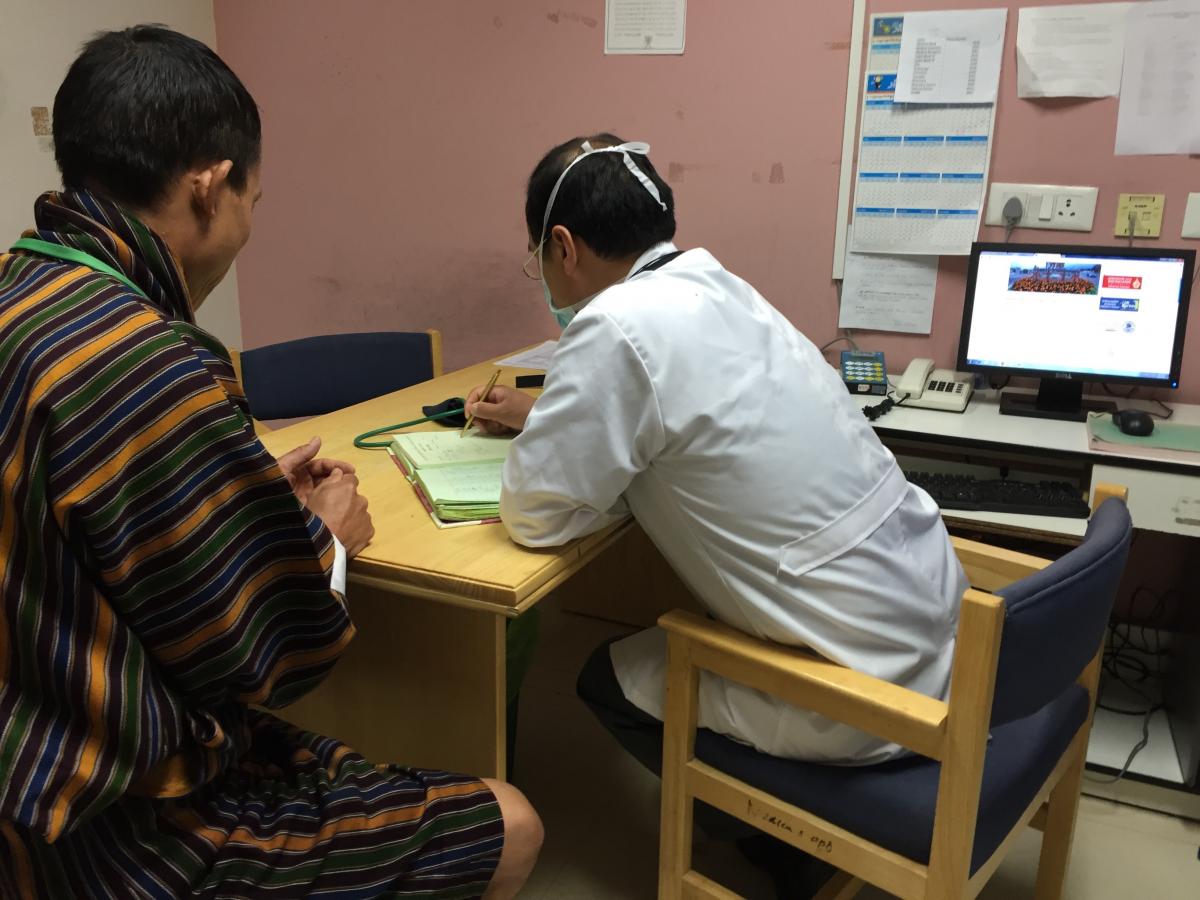

A tourist guide is receiving medical attention at the National Referral Hospital in Thimphu. Healthcare facilities in Thimphu are well equipped, easy to access, and free to all. Outside of the capital it is more challenging, as most people must walk several hours to reach one of the Basic Health Units, which can make the difference between life and death. (Photo: Peter Bilak)

When construction started on the East–West Highway in 1961, average life expectancy was 33, and almost a third of all children died before their fifth birthday. Bhutan was plagued by tuberculosis, sepsis, pneumonia and unsanitary living conditions. There were two hospitals, but only three doctors and two nurses in the entire country. Today, 90% of the population lives within three hours’ walk of one of over 200 Basic Health Units, or BHUs, each manned by two health assistants overseeing immunisation, sanitation, health education, outreach clinics and minor treatment. It’s worth the journey: free access to healthcare is guaranteed by the 2008 constitution, and largely thanks to the BHUs, life expectancy has risen to 70 and children are ten times more likely to survive to adulthood.

The BHUs stand at the base of a referral system that can send patients on to one of 22 district hospitals, and from there to three regional hospitals, including the national hospital in Thimphu, home to the country’s only MRI machine and sole CT scanner. It’s proved a successful way of using limited resources to make maximum impact, but although Bhutan’s workforce of 240 doctors and 950 nurses is still growing, it remains sorely overstretched. The World Health Organization calculates that a country requires at least 23 healthcare professionals for every 10,000 people. Bhutan has just 70% of that, and though its general practitioners are spread throughout the country, its specialists are clustered in the capital, on the wrong side of the East–West Highway for over 40% of its citizens.

First championed by the Fourth King in 1997, telemedicine—remote diagnosis and treatment—has been seen as a way to bring Bhutan’s scarce supply of medical expertise to its scattered population. A government duty to provide ‘100% nationwide access to a healthcare professional through technology-enabled solutions’ is even mandated by the country’s constitution, though progress has been patchy. A digital X-ray was set up in Mongur regional hospital in in 2000, Internet-linked electrocardiograms were installed at two hospitals three years later, and 14 telemedicine rooms, each with a desktop computer, webcam and Internet connection, have been set up. A 2008 attempt to link hospitals across South Asia fell through, however, and similar projects have suffered from a reliance on one-time donations for funding. This year, near the southern town of Gelephu, a BHU that was frequently cut off during the annual monsoon trialled a medical camera system with fibre-optic connections to the nearest hospital, yet rolling out such a system nationwide would be a huge undertaking. ‘We are trying to find out what is really required,’ says Gaki Tshering, the Department of Health’s telemedicine expert, ‘what kind of medical equipment will really benefit a basic health facility.’

Seeing and speaking to patients is one thing. Sending and testing samples is another. Most of Bhutan can only be accessed along mule trails, and several villages in the snowy north rely on mountain passes that open up only once a year. As the crow flies, however, even communities which take a week to reach on foot lie within 70 km (43 mi) of the East–West Highway, which is why the government has been eagerly exploring the use of drones since 2013. ‘The impact would be enormous in a mountainous country like ours,’ explains Tashi Duba, the Department of Health project manager who ran a drone testing programme. Samples could be collected within hours, and special drugs could be delivered where they are needed, making the most efficient use of a limited supply.

California-based startup Matternet joined with the World Health Organization and the government of Bhutan to conduct a trial project to send medical supplies to remote clinics in the Himalayan countryside. In this photo Matternet’s CEO Andreas Raptopoulos (in black) and Bhutan’s prime minister Tshering Tobgay (in red) watch a quad copter with a payload of about 1 kg (2.2 lb) in front of the National Referral Hospital in Thimphu. (Photo courtesy of Matternet.)

With funding from the WHO, Bhutan’s government contacted Matternet, a Californian company specialising in autonomous drone delivery systems. ‘Our vehicle is fully automated,’ says Andreas Raptopoulos, the company’s CEO and co-founder, ‘able to fly by itself beyond the visual line of sight of any observer. You have an iPhone app that you use to initiate the flight, and once the flight is initiated, the vehicle just follows the mission plan according to coordinates downloaded from our cloud system.’

In a nine-day trial in Bhutan’s highlands in 2014, Matternet outlined how BHUs could be connected to district hospitals. ‘Let’s say you have two or three drones at the hospital,’ explains Raptopoulos. ‘On demand, a flight is initiated to a clinic. The nurse there has a blood sample that she or he puts into a box on the vehicle, then they recharge the battery and send it back. From the hospital, they can report the result with a text message, and send medicine back to the patient, placed in the same box and sent to the clinic. Each leg of the trip would take a maximum of 30 minutes.’ Communications are encrypted, the drone has a parachute in case of malfunctions, and local conditions can be accommodated: ‘In Bhutan they asked us to be very careful not to fly over yellow roofs,’ says Raptopoulos, ‘because those are the monasteries.’

In Raptopoulos’ words, the system requires just three things: ‘Good GPS reception, cellular telephony, and electrical power for the places we fly in and out from.’ Unfortunately, none of these can be guaranteed in Bhutan’s remote areas. Where the drones are most needed, writes Tashi Duba, ‘there is no (reliable) GPRS/3G service,’ and despite Matternet’s confidence in Bhutan’s GPS signal, the drone did not land as instructed. ‘The medicines or samples might be misplaced, or the drone itself could get lost in Bhutan’s thick forests.’ Power is also a constant problem. Although almost all of the population has now been connected to a national grid, there are frequent brownouts and power fluctuations. Charging a Matternet drone’s battery, equivalent to charging four iPhones, is easier said than done.

A Matternet drone can fly for 10 km (6.2 mi) with a 1 kg (2.2 lb) payload, but most of the remote areas are further than 30 km (18.6 mi) from the nearest health centre, which means more landing pads, more refuelling areas, more people, and more training. Many telemedicine plans suffer from the same problems, says Gaki Tshering. Fixed facilities require ‘constant training, almost twice a year, because health workers aren’t stationed for long in one place. They move around a lot.’ Training costs money, and ultimately, stretched finances have put a stop to every major telemedicine project so far. The close to US$250,000 (€223,200) that Matternet requested to carry out a second feasibility study was, recalls Tashi Duba, ‘an astonishing figure for a country like ours’.

In the absence of major government projects, Bhutan’s medics have developed a home-grown solution. The Bhutan Telemedicine Group is a closed Facebook group comprising 320 doctors and nurses from around the country. Administered by a paediatrician, it has become a forum for consultation between doctors on smartphones. ‘Social media is picking up fast,’ says Gaki Tshering, ‘and doctors have adapted it to do consultations. I’ve seen 228 cases discussed in two months from 12 facilities. They discuss cases from alcoholic liver disease to meningitis, miscarriage, pneumonia, anaemia, and seizures. They describe a patient, say one with a skin rash, post a picture, then tag the dermatologists and say “please advise”. Other peers can view and comment. In an emergency, they can follow up with another message.’ Medics have even turned to instant messaging on WeChat: ‘They have a closed group of orthopaedics, a closed group of district medical officers, and that’s where they consult cases to get a quick response.’

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The new methods have had the greatest impact on newly qualified doctors, whose first posting is traditionally one to two years of work in a series of remote BHUs. ‘By consulting a specialist, they get the confidence they need,’ Gaki Tshering says. ‘They have to be the boss in those places, even if they’re new, and now they can say, “I’ve also spoken to specialists in the Thimphu national hospital and this is the reply. Even if you go yourself, you’ll get the same answer, so don’t travel for three days to get there.” It stops unnecessary referrals.’

The informal system is far from perfect. ‘We don’t have control or oversight over use,’ admits Gaki Tshering. ‘We’re concerned about confidentiality, and we don’t yet have a proper system to compensate doctors for their efforts.’ For her and her team, however, the doctors’ initiative is an outstanding example of teamwork and innovation that points the way forward, away from expensive projects and towards an official patient information system, synced from an app on a doctor’s smartphone to a national database. It’s not an idea from the WHO, or any external company, but one born in Bhutan, from medics striving to do the best with the little that they have.