Moving Pictures

Far from the glamour and big budgets of Hollywood or even Bollywood, Bhutanese film directors must also be their own promoters, distributors, ticket sellers, projectionists and road crew.

‘There’s a lot of light at play up in the mountains,’ says Ugyen Wangdi, with bright, dark eyes. A stocky man close to his 60th birthday, he leans across the café table, charged and brimming with impetuous energy. ‘Especially in the monsoons, when the clouds descend, sometimes you look up and all of a sudden a very strong light like a floodlight passes through some pocket and hits at a certain point. Then,’ he says, leaning back, ‘you see the mountain open up, and then, just like a curtain in a cinema, it closes again.’

More than four decades since he first picked up a camera, Ugyen Wangdi is still in love with the landscape of his native Bhutan. In the mid-1980s, he studied filmmaking at the Film and Television Institute in Pune, India, before returning home with ambitious plans. At the time, only a wealthy minority of Bhutanese had been to the cinema or ever watched television, but he was determined to make the country’s first feature film. To help ease his audience into the new medium, he based it on a popular folk song about divided lovers. To bridge the divides between Bhutan’s 22 languages, his Dzongkha script included ‘a lot of silence, to the extent that people thought something was wrong with the sound systems,’ relying on images to carry the narrative. ‘In our culture we have so much visual information,’ he explains. ‘It’s in our murals and our song and dance theatre. Like paint in the Sistine Chapel, they tell you stories. Our traditional masked stag and hound dance, for example, tells you the whole life story of a saint.’

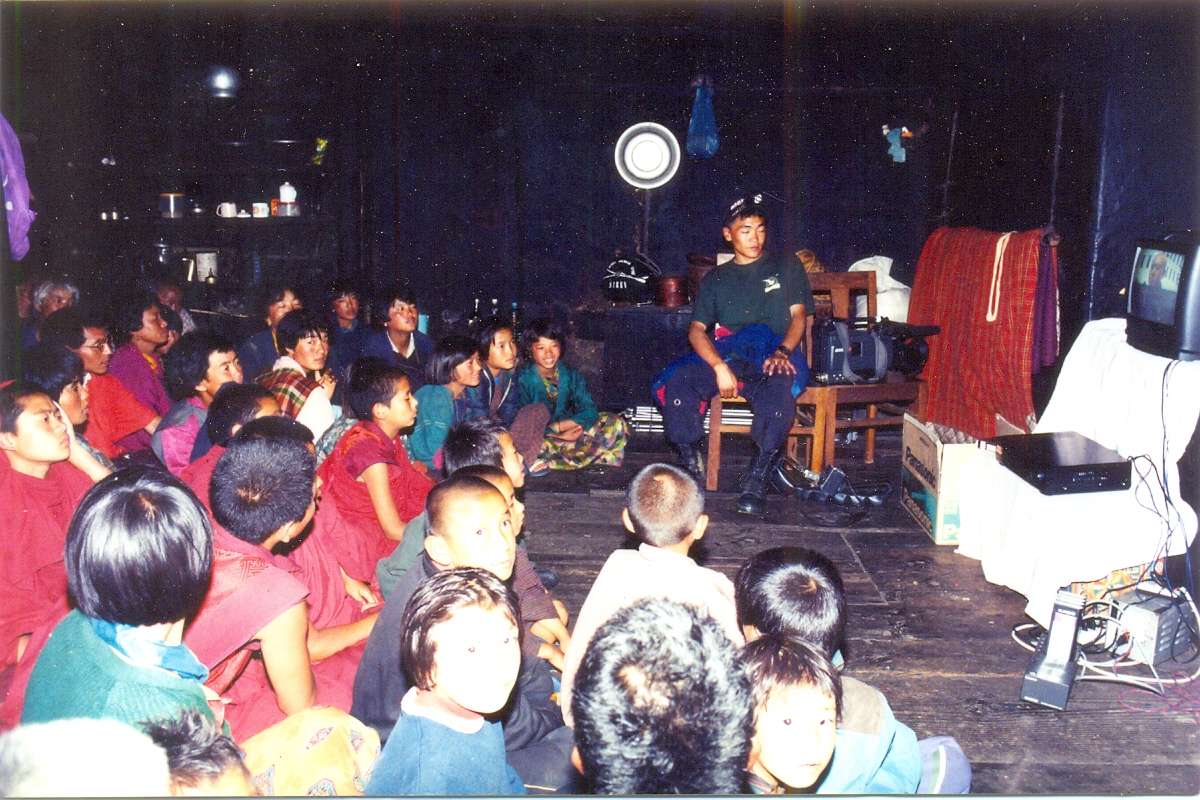

Villagers carrying a VCR, television, gen erator and fuel in exchange for the price of admission to watch Bhutan’s first film during its tour in 1988. All Bhutanese films are still distributed in this way. (Photo courtesy of Ugyen Wangdi.)

In 1988 he finished Gasa Lamye Singye. Among its first viewers was the Fourth King of Bhutan, who expressed concerns that the king in the film looked lonely and unhappy, but was satisfied with the explanation that costumes, props and extras for courtiers were beyond the production budget. With his blessing, the crew set out across the country, stopping in villages to sell tickets and mount screenings. ‘I would put up a screen out in a paddy field and charge a little bit for entrance,’ says Ugyen Wangdi, ‘but most of the villagers didn’t have a penny, so we let them watch for free.’

It was a sensation. ‘Because the story was a folk tale, people came to watch,’ Ugyen Wangdi remembers. ‘They were glued to it from the beginning to the very end, and would then go back to their homes and retell the whole story to those who hadn’t seen it.’ In the remote area of Laya, in which part of the film is based, the same people came to see the film on every night of its ten-night run. ‘They would shout out in the audience during the film: “This is the road to our home!” They really felt that the film was their thing. They sent me away with yak meat and other gifts, saying that such a thing had never happened in their village before.’

The crew would drive from location to location with a VHS tape containing the film and all of the equipment they needed, even a generator and the fuel it needed to run. Their small projector would become misaligned on the bumpy roads, so sometimes the film was shown on a large television set borrowed from a member of Bhutan’s royal family. When the road ran out, the tour would continue on foot over steep, mountainous terrain, with local enthusiasts carrying the equipment on their backs in exchange for viewing privileges. Ugyen Wangdi recalls the great lengths people would go to to watch his work: ‘These guys came on a four-hour trek down from their village to see the movie. On their way over, they had stopped every 30 minutes to hide brushwood torches in the bushes, so that after the film they could make the four-hour trek back to the village in the dark, finding each new torch as the one in their hand began to burn out.’

(Photo courtesy of Ugyen Wangdi.)

Cinema had arrived in Bhutan. Dechen Roder, a younger Bhutanese filmmaker whose work has featured at international festivals including the Berlinale and Locarno Film Festival, describes the next ten years as a time when the few films that were available were foreign and television was banned. Those with access to a TV set ‘were watching movies on VHS tapes,’ she explains, ‘and those were mostly pirated “cinema prints”, where you can see people walking around and hear comments from the audience.’ Nonetheless, the Bhutanese films that did make it to market were lapped up by an audience keen to watch films that they could relate to and understand, and up until 2000, the local film industry continued to grow and mature, until between ten and twenty feature films were being produced every year.

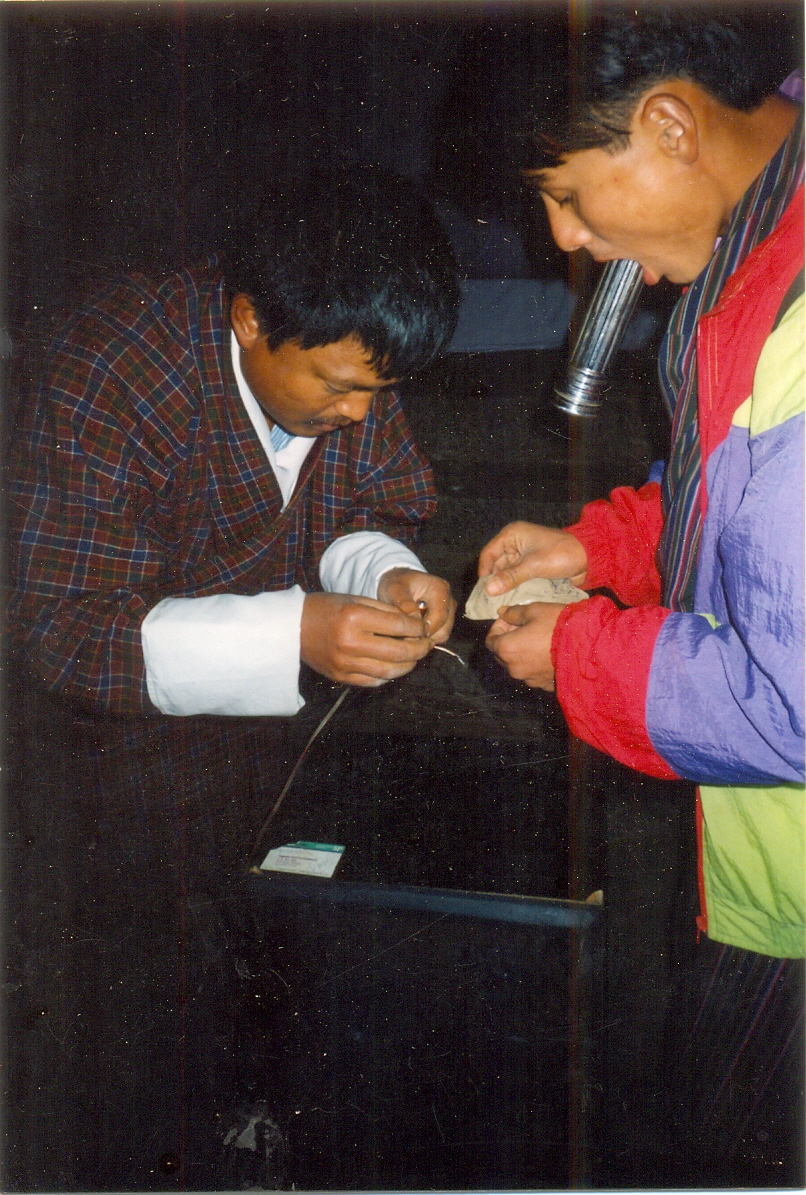

However, Bhutan’s tiny, captive market was and remains a double-edged sword. ‘Our industry is so small’, says Dechen Roder, ‘that if even one copy of a film is leaked, the filmmakers will lose their whole market.’ As a consequence, Bhutanese films are rarely released on DVD, for fear of pirate copies being made in India’s border towns. Instead, producers rely almost exclusively on ticket sales for screenings in order to recoup the money they spend on a film. What’s more, because distributing copies of a film to cinemas and screening halls would raise the risk of piracy, only one copy of a film is made, and it is carried around the country in person by the producer. ‘Usually, the producer sits with his film during the screenings,’ she says, ‘to make sure it can never be stolen or pirated.’ The tour that took Ugyen Wangdi’s film around Bhutan in 1988 has been effectively repeated with every new release for the past 28 years.

Most Bhutanese films exist as one single copy closely guarded by their directors or producers to prevent unauthorised copying. Filmmakers carry the film from village to village themselves, arranging showings and selling tickets. Pirate copies in a market as small as Bhutan could kill the prospect of recouping the production costs. (Photo courtesy of Ugyen Wangdi.)

Touring a single film around Bhutan’s 20 districts takes one year and covers roughly 200 locations. One reason that it takes so long is because cinemas only exist in the country’s main towns, so most screenings take place in alternative venues such as school halls, and tour itineraries have to take religious festivals and academic timetables into account. Tickets sell for 50 ngultrum (€0.67/US$0.75) to adults, 30 ngultrum (€0.40/US$0.45) to students, and the time on the road can be worth it: a typical Bhutanese feature film costs about 2,000,000 ngultrum (€27,000/US$30,000) to produce, and a big hit might make 2.5 million ngultrum (€33,000/US$37,500) from showings in the capital Thimphu, and then as much again from those in the rest of the country. Outlay for the tour is minimal. In most cases, the screening team turns up with a projector and uses a wall or a bed sheet to show the film.

Tshering Gyeltshen is an actor, writer and director responsible for three of the best-known films inside Bhutan. Strikingly handsome and animated by a boyish confidence, he is one of the country’s bona-fide stars. He remembers touring his breakout debut film in 2005, Perfect Girl. ‘You wouldn’t have to book a hotel, people would welcome you into their homes. There wasn’t much in terms of entertainment, so every time somebody came with a film, it was like a celebration. People in the next district would hear we were coming and be ready before we arrived.’ The film’s soundtrack was particularly popular: ‘We sold around 25,000 magnetic tapes with the soundtrack and 12,000 CDs.’

Internationally, Bhutan’s most famous film is Travellers and Magicians, a dense, mystical rumination set against ethereal Himalayan scenery. It has little in common with films popular inside the country. There, audiences flock to melodramatic love stories studded with songs and dancing, with narratives that spring from an earthy kind of social commentary, neither sophisticated nor purely sentimental. Because Bhutan has no graded ratings system, all of the films approved for public viewing by the regulatory body Bhutan InfoComm and Media Authority (BICMA), are equally family friendly, but they make their points even in the absence of adult content. Kuenden Lhatso, a recently released feature, begins with sweet scenes of a young man and a beautiful girl dancing by a mountain lake, singing about their love. But when her lover leaves town, the girl descends into severe alcoholism, destitution and madness. The man returns, finds her homeless and takes her in. She makes a fragile recovery. They are together again, and almost happy, and then she dies. The movie may be splashed with Bollywood magic, but it delivers a real punch.

Ugyen Wangdi, Bhutan’s first filmmaker, and the founder of its documentary production, setting up a showing of his film Gasa Lamye Singye. Ugyen Wangdi also introduced the present model of film distribution, visiting villages to mount film screenings. (Photo courtesy of Ugyen Wangdi.)

‘Anywhere in the world, visual mediums are the most powerful,’ says Tshering Gyeltshen. ‘They grab people and help us delve into social issues, and now with Bhutan becoming a democracy, there’s really no dearth of subject material for us to take up. Perfect Girl (a sympathetic portrayal of a call girl) was a commercial blockbuster because I took up a relevant social subject that everybody felt inside and nobody was talking about, and it struck a chord with our viewers.’ Prostitution, AIDS and alcoholism have all been tackled by Bhutanese cinema in films credited with opening up national debate. Taking a film on tour gives filmmakers the unusual experience of witnessing the impact of their films first-hand.

In his feature film Gawa, director Chand Rai addressed ‘night hunting’, the term applied to the Bhutanese tradition of boys whispering love messages to girls through their bedroom windows in the dark, or even quietly creeping into bed with them for furtive romantic encounters. In reality, it is often a cover for rape. Today, over 700 children born as a result of night hunting are not even considered Bhutanese, as they have no Bhutanese father in their birth certificate. On his two-year tour with Gawa, Chand Rai was approached several times by men and women after the screenings, keen to share their experiences with him. One was a nurse who said she was regularly asked by young girls for advice about abortions, which are strictly forbidden in Buddhist Bhutan. Having watched the film, she understood for the first time what may have been happening. Survivors of abuse revealed that they had felt stifled by the accepted culture around night hunting, and watching the film had given them the strength to speak out. ‘When people see and hear something together,’ says Chand Rai, ‘it gives them confidence somewhere in their heart.’

Chand Rai struggled to get Gawa past the censors. ‘I had issues with BICMA, who said this was going to paint the country in a very bad way, and it was against GNH (Gross National Happiness). To me GNH is that when you have a problem in your community, you stand up about it and you talk.’ Ultimately, the film was passed, and BICMA is often willing to discuss certification decisions. In two regards, however, BICMA tightly controls the characteristics of Bhutanese cinema for public screening. Firstly, films may be in Dzongkha or Sharchop, the language of eastern Bhutan, but they cannot be in English. Secondly, all characters must wear official national dress throughout the film, although over the years special dispensations have been given for nightclub scenes and other narrative situations where national dress might be inappropriate.

Villagers carrying a VCR, television, gen erator and fuel in exchange for the price of admission to watch Bhutan’s first film during its tour in 1988. All Bhutanese films are still distributed in this way. (Photo courtesy of Ugyen Wangdi.)

The demands of BICMA are relatively straightforward compared to those of the Bhutanese viewing public. Song and dance numbers are so much a part of Bhutanese cinema that, in the words of Tshering Gyeltshen, ‘no one has really tried not including song and dance in their film.’ Film length, according to Dechen Roder, is another concern. ‘If a film is under two hours, instead of two and a half or three hours then audiences feel cheated and ask to pay less for their ticket.’ None of these expectations are policed by critics. ‘A few years ago,’ she says, ‘people wrote reviews, but they didn’t go down very well with the directors. There were angry filmmakers every time a review was not favourable. Now it’s just better not to be a critic.’ Nominally, reviews are still written, but tend to be neutral synopses with details about the screening itinerary. ‘They point out the nice things about the film and leave it at that.’ In person, audiences are more open with their opinions. Ugyen Wangdi vividly recalls being approached by a large group of angry monks disappointed with his decision to cast their favourite comedian as a man about to lose his mind.

The golden age of Bhutan’s film tours may be coming to an end. ‘A kind of fatigue has set in,’ says Tshering Gyeltshen. ‘Now there’s cable TV, and everyone has a mobile and is busy on WeChat. Some people on the tours are actually starting to dictate how much they will pay to watch the film.’ Not only has digital technology made piracy more of a risk, filming equipment is also more widely available. ‘Now that anyone can be a film producer,’ says Tshering Gyeltshen, ‘there’s too many films on the market, some of which are poorly made. With too many films, sometimes you can have ten groups on tour converging in one place, such as a local festival, or tsechu. Fights can break out. Producers will be at each other throats, shouting “He came into my line first!”’ Tour teams have begun offering rescreenings of old films alongside new ones as an incentive: for a slightly increased price, people can watch two or three films instead of one.

Margins are so small in the Bhutanese film industry, that even apparently minor changes can have major effects. Soundtrack CD sales have dwindled to nothing, and film songs can only be traded with radio stations in exchange for advertising air time rather than cash. The knock-on effect of reduced receipts is less investment in film development, so the films themselves suffer. The latest plan from the Bhutan Film Association (BFA) is to set up something between a formalised tour system and a classic cinema distribution network. With 60 BFA screening kits placed across the country, the industry hopes to reduce the length of a national film tour from one year to between two weeks and a month. Each kit will contain one projector, two speakers, one screen and a Blu-ray player, and will be staffed by a trusted employee. The risk of piracy is increased, but the cost of renting equipment and personnel for a tour is greatly reduced at the same time.

After its one- or two-year lap of the country, the precious copy of the film ends up in the home of its creator. In theory, it could be printed on DVD, but so few people have DVD players, the risk of piracy is so high, and the cost of production is so significant that filmmakers usually feel there is more to be lost than gained by a DVD release. Rescreening is another option, but, as Yeshi Dorji, executive director at BFA explains, ‘rescreening is very rare, because people never come! Really, the last option is to sell the film to BBS [Bhutan Broadcasting Service] but they get very little money for that.’ The National Library of Bhutan requests that a copy be sent to its archives, but according to Ugyen Wangdi, ‘no filmmakers send their work to them in case it gets leaked.’ Instead, directors keep the sole copy of their films boxed up at home. Often, after their first tour, they are never shown again.

The only copy of Ugyen Wangdi’s Gasa Lamye Singye sits in his home on a Betamax cassette. Bhutan’s first feature film did not make money or earn a reputation abroad. An entire younger generation has never seen it and may never see it, but, he explains, its presence persists. ‘In my film of this folk story, there is a small, broken-down stupa at the point where the two lovers part. Recently I passed it by, and saw that the stupa had been rebuilt and was draped with flags. Villagers were dancing around it. I went over and quietly asked, “What are you all doing?” and they said “Don’t you know that this is the famous stupa where the two lovers parted? We can’t let it fall apart.” That wasn’t part of the folk tale before my film. I stayed with them as they retold the whole folk story. They didn’t know who I was. They told it, this time, and I kept quiet and listened.’