The Art and Science of Military Camouflage

In combat the element of surprise can be a tactical advantage that makes the difference between life and death. Drawing on nature, science and practical experience, designers create camouflage that can buy soldiers precious seconds in the field.

Cover Photo: A coloured etching of the Battle of Waterloo showing Prussian troops in brightly coloured uniforms. In an age of close combat, ready identification of friends and foes was of paramount importance. The advent of longer-range infantry weapons changed battle tactics, and effective concealment on the field became a priority. (Anonymous artist, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.)

‘In 2010, in trash-canistan, I got shot at, while walking next to guys in [MultiCam camouflage gear] (who were never targeted)!’ reads an anonymous comment at a military news site. ‘This happened three times, on two different patrols.’ This soldier was not alone. For nearly a decade, the American occupation of Afghanistan suffered from a grave case of the emperor’s new clothes. From the initial invasion in 2001 until about 2009, many US Army soldiers were sent into the country wearing a ‘protective’ camouflage pattern so ineffective that it actually seems to have attracted enemy fire.

The US Army had originally wanted to use the US Marine Corps’ camouflage pattern, but was denied permission. MARPAT (for Marine Pattern) is the intellectual property of the US Navy, the first camo pattern ever to be patented by a branch of the US military.

The documentation for that patent includes the statement, ‘Camouflage is an art in the process of becoming a science’, but the story of camouflage actually starts not with art, but with nature. For Charles Darwin, camouflage in the animal kingdom was further evidence for evolutionary adaptation. ‘When we see leaf-eating insects green, and bark-feeders mottled-grey; the alpine ptarmigan white in winter, the red-grouse the colour of heather, and the black-grouse that of peaty earth, we must believe that these tints are of service to these birds and insects in preserving them from danger,’ he wrote in his 1859 blockbuster, On the Origin of Species.

When the US entered the First World War in 1917, Abbott Handerson Thayer, one of the authors of Concealing Coloration, wrote to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, insisting that ‘what the government lacks is a board composed of painters—experts in matters of visibility.’

Inspired by Darwin’s observations, the eccentric American naturalist and painter Abbott Handerson Thayer published his own book, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, with his son Gerald in 1909. In it, they systematically classified naturally occurring camouflage patterns according to principles such as ‘mimicry’ and ‘disruption’ that could be replicated on paper and canvas.

One of the Thayers’ greatest breakthroughs, says University of Iowa camouflage scholar and professor of design history Roy Behrens, was their understanding of countershading. They observed that the undersides of many animals were lighter-coloured than their backs and heads, the reverse of the shadowing used by painters to make figures appear three-dimensional. Such countershading, they concluded, made animals look flat, helping them to blend into a busy landscape.

Humans, of course, have also made creative use of concealing coloration. In the time of Julius Caesar, ships were camouflaged with sea-blue wax, and during the US Civil War they were painted fog grey. Native American hunters wore buffalo hides to approach their prey, while Irish hunters covered themselves in bits of brush and branch to blend into trees. But the great innovation of the 20th century would be to distil all that elaborate costuming into principles that could be combined, customised and printed as a simple two-dimensional pattern.

The word ‘camouflage’ is taken from camoufler, which means ‘to disguise’ in the French thieves’ cant of the early 20th century, and it was during the First World War that the French army began assembling top-secret squads of artists to disguise its troops. Dubbed camoufleurs, they created drab hooded smocks and painted screens in natural colours, to blend soldiers and equipment into their surroundings (what the Thayers would have called ‘mimicry’). They even constructed false dead trees that concealed sentry posts, and phoney horse carcasses that hid snipers.

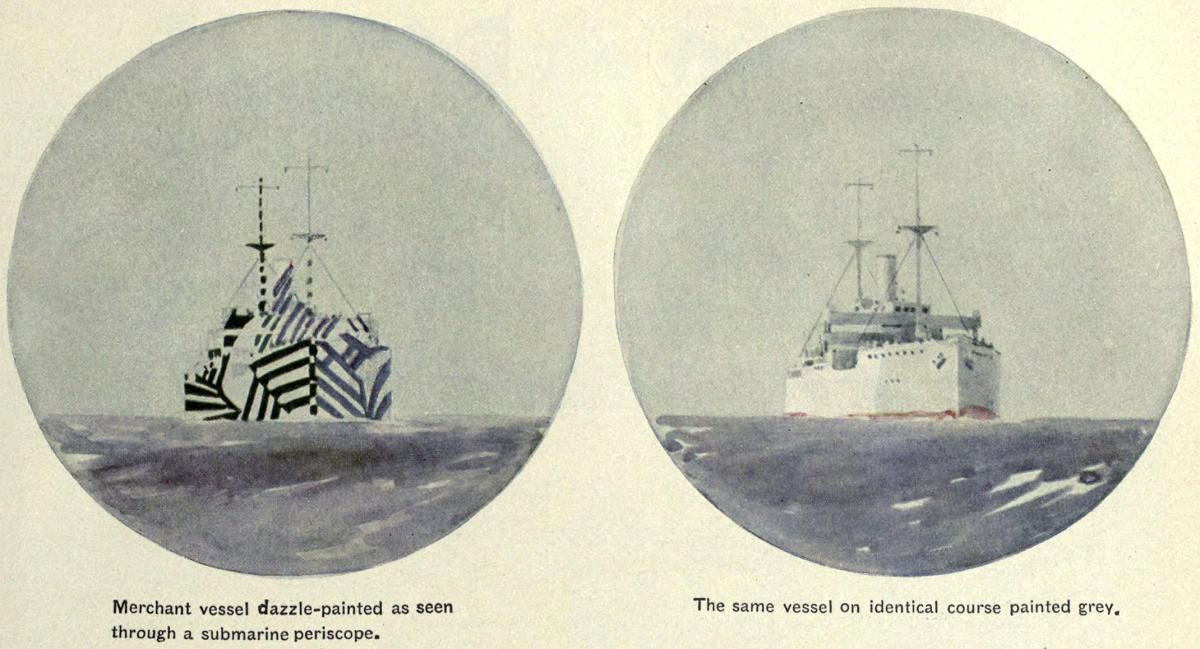

When the UK joined the war, it followed suit. Notably, the UK marine artist and naval conscript Norman Wilkinson pioneered an effort to paint navy ships in bold, abstract patterns called ‘dazzle’. These bands, stripes and dots broke up the ships’ lines, making them difficult to interpret. (The Thayers called this ‘disruption’.)

Ships during the First World War were hard to conceal because of constantly changing weather conditions and because of the smoke they produced, so instead of hiding them (‘mimicry’), the British used complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting colours to make it difficult for the enemy to estimate their type, size, speed and direction of travel (‘disruption’). Each ship’s dazzle pattern was unique to avoid making classes of ships instantly recognisable to the enemy. On the image above, two otherwise identical ships as seen through a submarine periscope, one with dazzle painting and one painted grey.

Designed largely by women at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, dazzle patterns began appearing in stunning planes of colour and stark lines on naval ships during the First World War. And despite some resistance from ship captains, by the Second World War these multiplied into hundreds of patterns and paint combinations for both UK and US ships. Although little could be done to shield a ship against sonar or to hide the tell-tale plume from its smokestack, it was hoped that the visual flash and pomp of dazzle paint would make it harder for enemy submarines to figure out the direction in which it was heading. ‘It wasn’t a matter of making it invisible,’ says Behrens. ‘It was a matter of throwing off [U-boat] targeting, which was quite complex.’ (Some ships had fake bow waves painted on the wrong end, for the same purposes.)

Did dazzle painting work? The results of some trials were positive, but Wilkinson himself was not so sure. ‘From a careful examination of the whole of the evidence, no definitive case on material grounds can be made out for any benefit in this respect from this form of camouflage,’ he wrote of his own dazzle painting technique, back in 1920. ‘At the same time the statistics do not prove that it is disadvantageous, and in view of the undoubted increase in the confidence and morale of officers and crews of the mercantile marine resulting from the painting which is a highly important consideration, together with the small extra cost per ship, it may be found advisable to continue the system, though probably not under the present wholesale condition.’

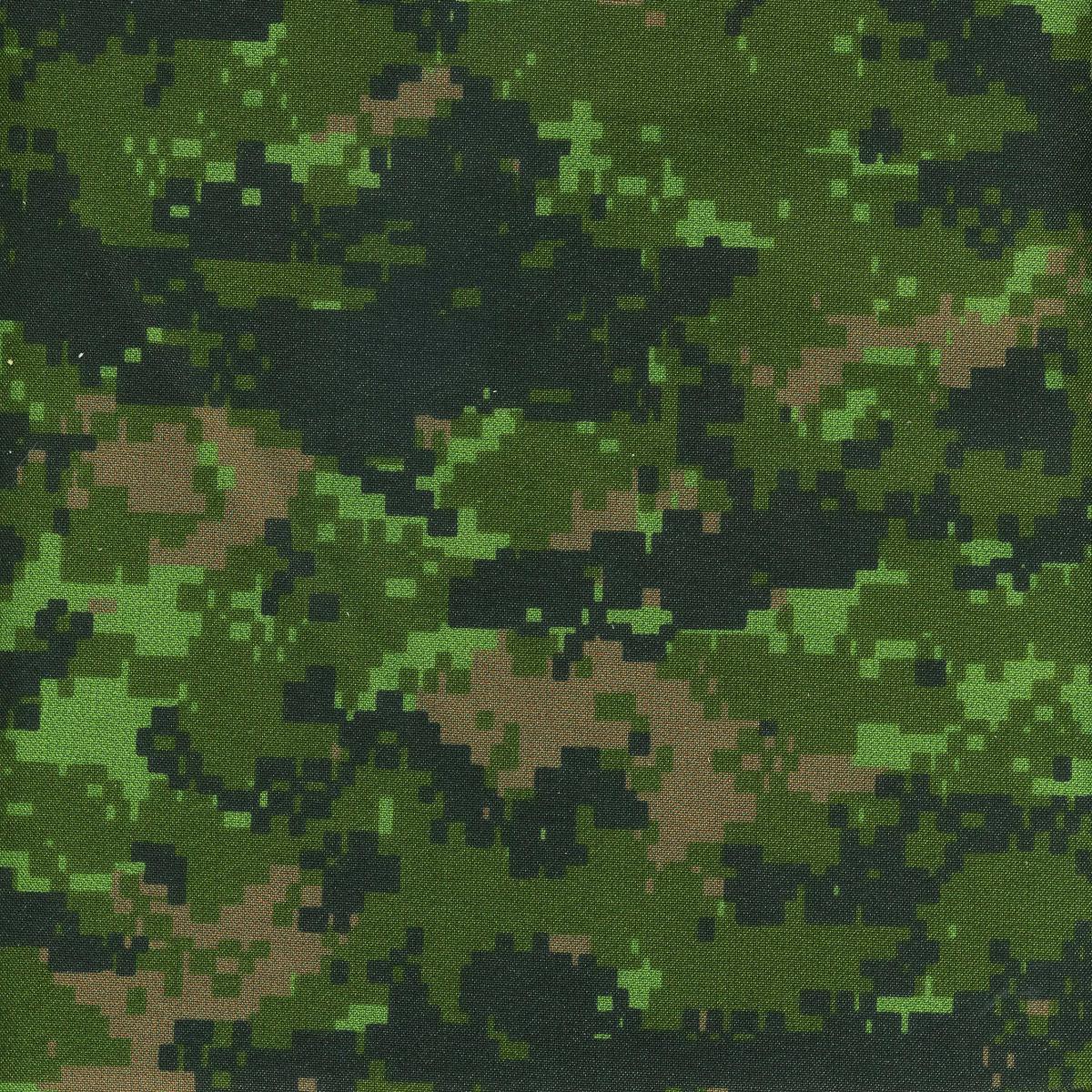

Despite never having worked on camouflage, some of the era’s most avant-garde artists, including Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, eagerly embraced association with the visually engaging dazzle. ‘It was us who created that,’ famously boasted Pablo Picasso at the sight of a camouflaged cannon in Paris, towards the end of the First World War. Today, Braque and Picasso might be forgiven for thinking that they were still the inspiration for contemporary camouflage. Cutting-edge ‘digital’ prints now feature cascades of small and large right angles reminiscent of vintage Cubist and Futurist works.

According to digital camouflage designer Guy Cramer, the best of these blocky patterns are the result of a unique fractal approach to camouflage that appropriates repeating mathematical patterns found in nature. ‘The simplest example is that the smallest leaf of a fern is almost identical to the largest leaf of a fern in appearance and it’s only scale that’s the difference between the two,’ says the founder and CEO of Canadian company HyperStealth.

A Slovakian MiG-29 in Digital Thunder camouflage developed in 2006 by HyperStealth, a private Canadian military contractor. The three colours (Blue, Medium Gray, Light Blue Gray) are chosen to blend in with overcast and blue skies as well as with land and sea. (Photo courtesy of HyperStealth.)

‘We’ll take these shapes that are found in nature and we’ll embed them into the camouflage. So your subconscious takes that one and logs it with everything it’s seen prior and says, “Okay, these are all the right shapes—ignore them all.”’

He notes that the brain will come back to that pattern and analyse it again, eventually discovering the anomaly. But the time that it takes to do that can make a difference to an exposed soldier; in one test by the US Army, it took an average of 30 seconds for a human subject to find a figure camouflaged by a HyperStealth pattern, says Cramer. Four to six seconds before recognition is considered excellent performance.

Ever since Afghanistan, however, ‘pixelated’ patterns have inspired more scepticism than confidence among US soldiers. ‘There are no right angles in nature,’ says Ernesto Rodriguez, spokesman for Crye Precision. Crye developed MultiCam, the blotchy brand of camouflage that was distributed to soldiers in Afghanistan after it became clear that the Army’s own pixelated pattern wasn’t working.

The computer-generated digital camouflage pattern CADPAT used by the Canadian Forces was the first pixellated digital camouflage pattern to be issued. CADPAT is also designed to reduce the likelihood of detection by night vision devices. Use of CADPAT by civilians is illegal.

MultiCam is a seven-colour, multi-environment camouflage pattern designed for use by the US Army. It was developed by Crye Precision and is also sold for civilian usage.

The Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP), is the military camouflage pattern used on the United States Army’s Army Combat Uniform. Its pixelated pattern is similar to the Canadian CADPAT scheme. The effectiveness of the pattern was questioned, leading to replacement of UCP in 2014 by Scorpion, a pattern similar to MultiCam. (wiki)

‘You go into the jungle, you go into the desert, you’re not going to find anything that’s a square,’ he explains. ‘If you look at the entire pattern of MultiCam and how it repeats, you see a horizon, you see vertical elements that look like a tree, or what a shrub or treetop will look like at a certain distance. We knew you needed varying sizes of these shapes because the human form is easily recognisable to the human eye and these shapes disguise all that. It’s about looking at nature.’

Crye Precision and HyperStealth Technologies are two of the world’s highest-tier camouflage makers, and in some ways, they represent the two poles of contemporary camouflage theory. Crye Precision favours organic-looking shapes and print sizes. It currently supplies the UK, German, and Australian militaries, among others. (Poland has used a ‘knock off’ version of MultiCam, Rodriguez adds.) Like the US Army’s failed pattern, MultiCam is designed to camouflage in a variety of environments, from desert to jungle. The difference is that it actually seems to work, something Ernesto attributes to the brand’s darker colour palette and softer shapes.

The secretive HyperStealth, on the other hand, creates distinctly digital patterns similar to MARPAT, on which the Army tried unsuccessfully to base its own pattern. Nearly five million military-issue uniforms across 50 countries in the world sport the Canadian company’s pattern. HyperStealth deals solely in fractal prints, and seems bent on pushing the frontiers of science as far as it can, recently announcing the creation of a real, working invisibility cloak. (It has, however, declined to show its invisibility cloak publicly, citing patent concerns.)

The US Army soldiers walking into the line of fire in Afghanistan were wearing a sandy, Army-designed camouflage called the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP). A digital print, it was not dissimilar to those created by HyperStealth, but it featured mostly light shades and lacked the dark, shape-disrupting streaks that have evolved throughout camouflage design since early 20th-century dazzle. This proved to be a serious flaw. Due to an optical phenomenon called isoluminance, lighter colours tend to blur together when viewed from a distance, appearing to lighten. In a natural world full of shades and shadows, this effectively causes anyone wearing those colours to stand out instead of blending in.

As Cramer points out, that would be true even if UCP were a more organically shaped pattern. ‘After UCP, everyone thought that digital camouflage was dead, that it was a trend or a fad,’ he notes with some bitterness. ‘That was never a digital camouflage issue, that was a coloration issue.’ His arguments for digital camouflage have so far failed to gain the trust of troops on the ground. As of January, 2016 all US Army soldiers will be transitioned out of their old uniforms and into a splotchy MultiCam-based pattern.

The question remains: how much protection can even the best camouflage offer in an era when technology can read faces in the dark, scan for heat signatures from continents away and identify strangers’ faces in milliseconds? And what colours and shapes can camouflage designers successfully mimic, now that danger is no longer limited to traditional and predictable battle fields, but spills out into a civilian milieu of soft targets? A new generation of artists is forging the way forward by entirely redefining what it means to blend in.

In 2013, New York-based artist Adam Harvey, who gears his experiments in camouflage towards civilians, created a metal-lined burka to protect against thermal sensing, one way in which drones target victims in danger zones like Waziristan or Pakistan.

‘I think the term “camouflage” is too wrapped up in military usage. It’s something we do every day, when we fit into social settings, when we consider the way we speak, etc.,’ says Harvey. He compares camouflage to fashion, something to buy and update with each new season and technological environment. According to him, camouflage is part of staying ahead of the trend.

University College London artist Yanchao Li may be doing just that by designing his camouflage specifically for the algorithmic eye. In 2015 he introduced robotic prosthetic limbs as a way to help users sidestep gait recognition software, which identifies people based on the way they walk. Similarly, Harvey’s current project, ‘CV Dazzler’, repurposes old-fashioned dazzle to foil facial recognition software, showing users how to use make-up or stickers to break up the lines of a face and to obscure the identifying ratios between nose, eyes and mouth.

‘You can invent drones. You can invent radar. But as soon as you invent a new means of detection, then there’ll be a new means of concealment or diversion,’ says Behrens of the challenges ahead for would-be camoufleurs. Then he notes matter-of-factly, ‘And if you invent a new diversion, there will be a new means of surveillance.’