Rwanda’s War on Plastic

Plastic bags are such an ubiquitous part of the modern world that it is difficult to imagine life without them. Convenient though they may be, they pose a severe environmental threat, and Rwanda has made a commitment to eliminating them.

Cover Photo: Rwanda almost destroyed itself but has now become one of the top African countries for enterprise and development. KN 3 Road is the main boulevard leading to the Central Business District of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city. Kigali has been named by various surveys as the cleanest and greenest city on the continent. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

Kimironko Market, a bustling open-air plaza at the edge of the Rwandan capital, is in many ways a typical African bazaar. Seven days a week, throngs of Kigali’s 1.3 million residents file through its narrow paths flanked by mangoes, bananas and avocados. Finely milled flour is piled in mounds, and slabs of goat and cow carcasses hang from metal hooks. The smells, satisfyingly pungent, reflect the freshness of the produce. At the front entrance, the air is heavy with the aroma of fish sourced from the waters of Africa’s Great Lakes region, but farther into the market the scent gradually gives way to the smell of spices, sweat, and slowly ripening fruit, complementing the scent of rain-soaked earth that drifts in from surrounding hillsides.

At Kimironko, though—and all across this tightly packed country of 12 million people—one item is conspicuously absent. Most other markets in sub-Saharan Africa are overrun with plastic, the thin translucent bags used for packing meat and spices, the heavier black bags used for produce, and a whole lot of both drifting through the air, clogging up the drains, and matted with mud on the ground. In Rwanda, however, the manufacture, sale, and use of polyethylene bags have been illegal since 2008, with violators facing hefty fines or even jail time. And although a lucrative black market for plastic bags persists, a majority of Rwandans have transitioned to reusable or biodegradable alternatives. At Kimironko, this means business for locals like Theoneste Vuguziga, who sells an assortment of shopping bags from a stand inside the market. Hanging on hooks are his flashier, more expensive items: brightly coloured cloth bags and oversized waxed-paper bags imported from India, adorned with pictures of elephants, big cats, and somewhat out-of-place snow-capped mountains. The biggest seller, though, is Vuguziga’s most affordable product: a simple brown paper bag that sells for 100 Rwandan francs, the rough equivalent of US$0.13 or €0.12. Although Vuguziga’s profit is modest, the bags help to feed his family and contribute to what most vendors and customers agree is a more environmentally friendly, not to mention pleasant, market experience.

A cheerful display of biodegradable plastic bags hanging in a stall in Kimironko, the largest market in Kigali. They provide a convenient and legal (but more expensive) alternative to polyethylene bags whose sale and use were banned in 2008. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

‘Before the ban, plastic bags were everywhere,’ says Rebecca Niyongabo, a customer shopping for beans at an adjacent stall. ‘The wind would blow them into the air; babies would eat them; people would burn them in their rubbish and the entire neighbourhood would smell. It was a mess.’

Although Rwanda’s ban on plastic bags has long made international headlines, the law itself is hardly unique. Since the late 1990s, various municipal, provincial and national governments have enacted similar legislation, but generally with mixed success. In 2002, Bangladesh became the world’s first country to institute a full ban on plastic bags, which were found to have clogged the country’s drainage system and contributed to a bout of catastrophic flooding. Other nations, including many in Africa, eventually followed suit. As of 2013, according to the Earth Policy Institute in Washington, DC, 19 countries on the continent had enacted either full or partial bans, often targeting thinner bags that are more easily carried away by the wind. This crackdown on polyethylene has been motivated by several factors, including the bags’ contribution to flooding and soil degradation, and their often-fatal consumption by animals. In Mauritania, which banned plastic bags in 2013, 70% of sheep and cattle deaths in the country’s capital have historically been caused by plastic bag ingestion.

When passengers arrive in Rwanda their belongings are closely inspected. For plastic bags.

Rwanda’s ban, however, is exceptional in one important aspect: it’s stringently enforced. Unlike in many countries with similar laws on the books, Rwanda’s law enforcement agencies and environmental stakeholders have made the campaign against plastic bags a top priority. Following the law’s enactment, the Rwanda Environmental Management Authority (REMA), an agency within the Ministry of Natural Resources, launched a nationwide campaign to create awareness of the ban and educate children and adults on its importance. Today, signs at Kigali International Airport and many border crossings warn visitors that plastic bags will be confiscated. In markets across the country, it is still possible to find hawkers selling fruits or cakes that are wrapped in plastic, or underground polyethylene traders dealing in illicit bags from street corners or back alleyways. For the most part, though, Rwandans obey the law. In interviews, vendors at Kimironko Market spoke of visits by undercover inspectors. Those caught using non-biodegradable plastic, they said, are typically fined 50,000 francs (US$61, €67), enough to keep most traders in compliance. The ban’s success is also partly due to traditional Rwandan culture, which places an emphasis on obedience to authority and on cleanliness. Kigali, which is widely regarded as one of Africa’s cleanest cities, won a UN Habitat Scroll of Honour award in 2008 for its emergence as a ‘model modern city’, including its improved collection of rubbish and ‘zero tolerance for plastics’. Unlike Rwanda’s neighbours, where travellers regularly toss refuse from vehicle windows, littering in the country is almost non-existent.

The central covered area of Kimironko market offering fruit, vegetables, herbs, spices, dried beans, dried fish and rock salt. Shoppers usually bring their own bags to carry the products they have purchased. The market boasts its own radio station which plays lively gospel music and also provides information about the market to traders who wish to know what the wholesalers are carrying, and at what price. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

‘Rwandans are a proud people,’ says Rose Mukankomeje, REMA’s director general and the plastic bag ban’s self-described ‘enforcer’. ‘We don’t like things dirty. Our countryside is not a dustbin.’

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.As Mukankomeje explains, the bag ban is only part of a wider national conservation strategy that aims to boost resilience to climate change, combat deforestation and prevent the continued erosion of the country’s famed mist-covered hillsides. Although there is yet to be a quantifiable study that assesses the law’s specific impact, Mukankomeje says the ban has contributed to reductions in animal deaths, soil erosion, flooding and even malaria, the last by reducing the prevalence of potential mosquito breeding grounds. In addition, she argues, Rwanda’s commitment to preserving its environment has helped spawn a growing market for ecotourism, which is buttressed by the presence of some of the world’s last remaining mountain gorillas. Slowly, Rwanda’s reputation for order, cleanliness, and natural beauty is beginning to overtake the country’s more infamous place in popular imagination as the country only 22 years removed from its 1994 genocide, in which as many as a million ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutu were slaughtered in just 100 days.

Other countries have taxed and/or regulated the use of plastic bags. Rwanda went a step further. Non-biodegradable plastic bags have been illegal since 2008, and unlike most countries, Rwanda has strictly enforced the ban.

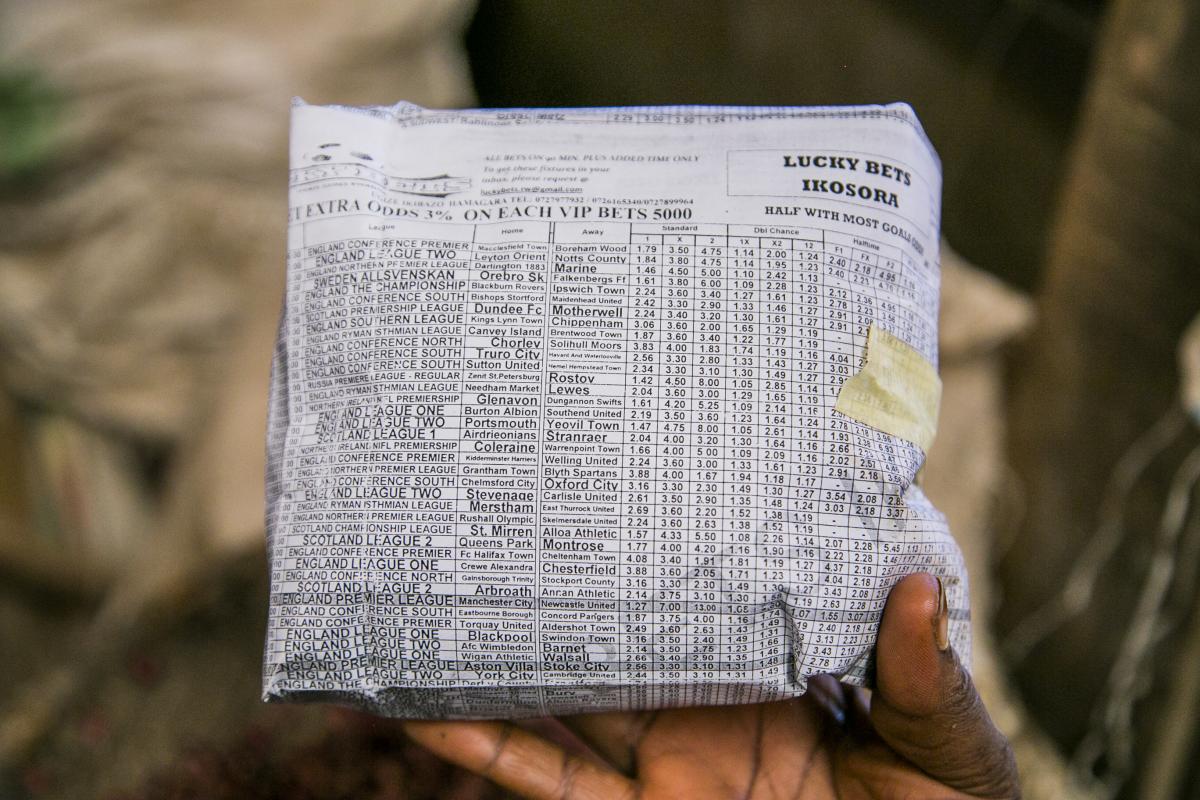

Whatever role the bag ban has played in boosting Rwanda’s image, however, it has also come with some unwanted consequences. For traders and customers alike, the most pertinent issue is cost. Michael Rozanski, a German baker in Kigali, says the waxed-paper bags he uses to package bread cost four to five times more than similar bags made of plastic. In Kimironko, most meat and fish, due to a lack of locally made alternatives, are packaged in biodegradable plastic bags imported from Britain, the associated costs being passed on to customers. In an effort to gain a competitive edge, some vendors devise creative alternatives. Rather than hike her prices, Marionne Muteteri, a Kimironko bean seller, serves her product in one-kilogram sacks made from betting sheets she buys on the cheap from local gambling houses. Customers, therefore, arrive home with an added bonus: odds on already-played football matches from the Belarus Premiere League, South Korean K-League, and German Bundesliga.

Marionne Muteteri, a Kimironko beans’ seller, serving her product in one kilogram paper sachet made from betting sheets that she buys on the cheap from local gambling houses. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

A paper bag containing one kilogram of beens sold from the Kimironko market. Some bean vendors manage to buy on a cheap price these betting sheets from gambling houses as a solution to the ban of plastic bags in the country. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

The increased costs associated with the ban, however, have been hardest on local manufacturers. Because the law also applies to most forms of plastic packaging, companies producing packaged foods, beverages, and household goods have been forced to change the way they ship their products. Due to obligations under various international trade agreements, however, the Rwandan government is unable to ban the use of plastic packaging for competing imports. This puts domestic firms at a distinct disadvantage. According to Alex Ruzibukira, an official in the Rwandan Ministry of Trade and Industry, authorities are working to address this problem. Already, he says, one investor is in the process of establishing a local facility to produce biodegradable plastic. In addition, a government study will soon be underway to assess the feasibility of an integrated packaging plant; both initiatives could potentially reduce producers’ costs. Nonetheless, many Rwandan companies affected say it would have caused far fewer headaches to simply offer them exceptions to the law.

While most developing countries have other priorities, Rwanda has pioneered effective environmental protection and sustainable use of resources. Today, just two decades after its civil war, Rwanda is one of the cleanest countries in Africa.

‘We’ve been lobbying the government on this for many years,’ said one local manufacturing executive who asked to remain anonymous. ‘Nothing has changed, and we don’t believe it will. So we’ve just been forced to adapt.’

There are some local entrepreneurs, however, who’ve managed to exploit the country’s war on plastic to their advantage. Wenceslas Habamungu, the general director of Eco Plastic Ltd, is one of them. Back in 1999, when many of Kigali’s now-pristine boulevards were still overwhelmed with rubbish, he and his brother Paulin Buregea established COPET, Rwanda’s first private waste collection company. Nine years later, after the ban came into effect, they ran into a conundrum. Although authorities had granted their company an exception to the law, which allowed them to continue to use plastic bags for waste collection, all domestic plastic producers had relocated to neighbouring countries or gone out of business entirely. After meeting with the authorities, they were given the choice of importing bags under strict conditions, or establishing a recycling plant to make their own.

Ongoing production activities inside the Eco Plastic. Located at 15km out of the city centre, the plant is the biggest plastic recycler in the country. (Photo: Cyril Ndegeya)

Ultimately, the brothers chose the latter. After all, while the law was tough with requirements for plastic packaging, it did allow for the use of plastic bags by hospitals, as well as certain forms of plastic sheeting for agriculture and construction. Meanwhile, the plastic used to package imported goods, which was typically confiscated at customs, meant there’d be a ready supply of material to recycle. Today, six years after its establishment, Eco Plastic Ltd collects more than 80 tonnes of polyethylene every year, churning out bright yellow bags for hospital waste, tubing for use in tree nurseries, sacks for post-harvest storage, and the rubbish bags used by Buregeya’s COPET. The factory, like the items it produces, is largely hidden from the public eye, set inconspicuously on a hillside next to a dirt road outside the capital. Here, just inside the gate, rows of discarded mattress sheets, mosquito net coverings and reams of bubble wrap hang drying in the afternoon sun after being washed by some of Habamungu’s 50-plus employees. Soon, the plastics will be taken inside the factory, mixed with additives and colours, and pumped through a series of machines that heat them to 180°C (356°F) and reshape them into various recycled products.

This is plastic Rwandan style: orderly, law-abiding, and mostly out of sight.