Ships That Dance in the Night

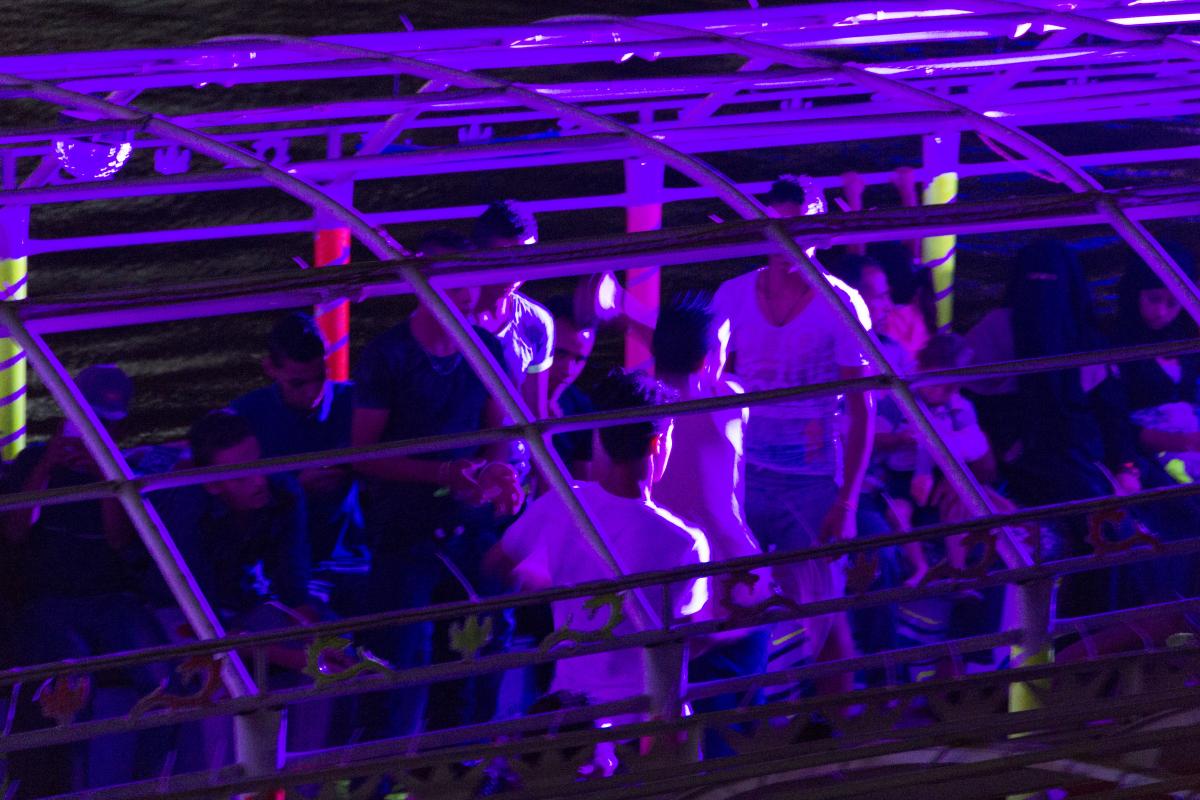

At night, the Nile is home to the extravagant floating nightclubs frequented by Cairo’s wealthy elite, but also to the mahraganat boats, downscaled versions accessible to the working class.

From earliest antiquity, the Nile has been the source of Egypt’s life and the shaper of its civilisation. Fundamental to the agriculture, transportation and economy of this otherwise arid land, the river inspired early historians to call Egypt ‘the gift of the Nile’. In more recent years, specifically since the days of Anwar Sadat’s neo-liberal open-door policy, the Nile has been the setting of an explosion of bourgeois entertainment facilities in Cairo, including luxurious ships where the Cairene elite enjoy clubbing, dancing, and drinking at prices up to 1,000 Egyptian pounds (€112 or US$128) per hour.

Since the Arab Spring revolution of January 25, 2011, however, this playground of the rich has been invaded by the mahraganat boats, working-class takes on the floating nightclub that are clearly rough-hewn, but that offer their services for a mere five pounds (€0.55 or US$0.65).

Ahmed Salim, a worker on a mahraganat boat, says that ‘the fact that we now operate these kind of boats at night with special lighting and music has meant that we also enjoy nightlife but without the necessity of paying your entire salary for one night out.’

Mahraganat means ‘festival’, something lavish, loud, vibrant, joyful, and perhaps at times even messy. It is a fitting term for a musical style characterised by energetic dance beats, hypnotic, repetitive melodies and bold, sometimes coarse lyrics. Owing as much to the working-class shaa’bi music of the 1970s as to hip-hop, and produced in makeshift studios, it is a streetwise blend of heavily autotuned vocals accompanied by both traditional and electronic instrumental timbres. Its youth-driven, socially conscious texts reflect life in the ghettos where its artists were born, grew up and still live today, despite the fact that their work has blossomed into a widespread subcultural movement.

The boats named after this musical genre are similarly products of the social movements and pressures of post-revolution Cairene life. Inspired by the breakdown in class barriers during the revolution, owners of small boats gave their ships a facelift, taking elements of the extravagant pleasure boats of the upper class—the flashing coloured lights, loud music and dancing girls—and combining them with the mahraganat’s working-class sensibilities.

The boats’ patrons are also largely working-class people eager to spend a night out without spending their entire salaries. They come, however, from diverse religious, ideological and political backgrounds. Less frequent, but not entirely uncommon, are men in long beards and women in burqas, equally at home in the mosque or on the mahraganat. ‘I come with my children here because I enjoy the music and the trip on the Nile. My children like to dance and make fun of others dancing. There is nothing wrong about this,’ said one customer from behind her veil.

Another patron, Salma, says she loves everything about the concept of mahraganat: the sweeping synths and chattering cymbals of the music, as well as the vibrant, energetic atmosphere. The lyrics celebrate and give expression to the realities of her everyday life, an invitation not only to enjoy the party, but also to escape those realities, if only for one night. But Ahmed, a worker on the boat, admits that although the tracks feature politics, their function is not primarily political: ‘The songs talk about social, political and economic issues, but the main thing for these guys, really, is to get the party started.’ As another partygoer says, ‘to listen to music about your everyday life is an incentive to move every part of your body to that rhythm.’

The affluent customers of the luxury establishments on the river criticise the mahraganat boats, complaining about ‘noise pollution’ and arguing that the Nile should be reserved for the higher segment of society and its refined culture. Nonetheless, it appears that the rocking boats are here to stay. ‘On the Nile banks, there are different realities and possibilities of living,’ Ahmed says, ‘but here the boats float on the same water, and the same darkness covers us all.