Our Country is The World

In the wake of the Second World War, former bomber pilot Garry Davis decided that the only way to ensure lasting peace was the establishment of a unified world government. He launched his effort to bring that about by renouncing his American citizenship and travelling with a self-issued World Passport.

Cover photo: Garry Davis, right, the holder of World Passport number 1, in trouble in Basel, Switzerland in 1975. Davis was sentenced to seven days’ imprisonment by a Swiss court for illegal border crossing and was deported to France. In 1948 this former American citizen gave up his US passport, became a self-proclaimed world citizen, and began to travel the world with his self-issued document. (Photo courtesy of Keystone Press Agency/Keystone USA.)

‘Passport please?’ For citizens of prosperous, democratic states it’s a casual question, almost a sort of welcome. For the rest of the world, however, it means suspicion, scrutiny, a screening out of undesirables. Imagine then, a world passport, one that would be not just a travel document, but a symbol to unite all mankind instead of an instrument to divide people into national entities. Imagine ‘no countries […] nothing to kill or die for,’ as John Lennon put it. Imagine whistleblowers and political activists travelling and working freely, and artists like Ai Wei Wei staging their provocative art all over a world where anyone can go anywhere anytime.

That’s exactly what 34-year-old American veteran and former Broadway actor Garry Davis (1921–2013) did when he walked into the US embassy in Paris on May 25, 1948 to surrender his passport, renounce his nationality and declare himself to be a ‘citizen of the world’. Politely but firmly he was escorted out, officially still an American citizen though no longer in possession of an official passport. A few months later, he pitched a tent on the pavement of the Palais de Chaillot in Paris where the delegates of the United Nations were to assemble. Davis was ordered to leave, but refused, declaring before the gathering crowd that he was no longer in France but in ‘international territory’. After forcing his way into the UN session to protest against what he saw as the inadequacy of that organisation he was arrested and forcibly removed, and the French wanted to deport him but couldn’t, as he had no passport.

After the horrors of the Second World War, the concept of a world passport appealed to many as an apolitical document of identity based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and notable statesmen and intellectuals expressed support for the idea of world citizenship.

It may have seemed like a prank at the time, with Davis as the cheeky youngster loudly drawing attention to the nakedness of the emperors of his day, but it was an event leading up to one of the most utopian visions of the 20th century, and in 1953 Davis founded the World Government of World Citizens (WGWC), an organisation that would seek to fulfil Article 13-2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: ‘Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.’ Davis believed that a world passport would be an important step towards bringing this to pass, a document that would overcome nationalism and repression, a symbol of ‘the fundamental oneness and unity of the human community’.

You seem to enjoy a good story

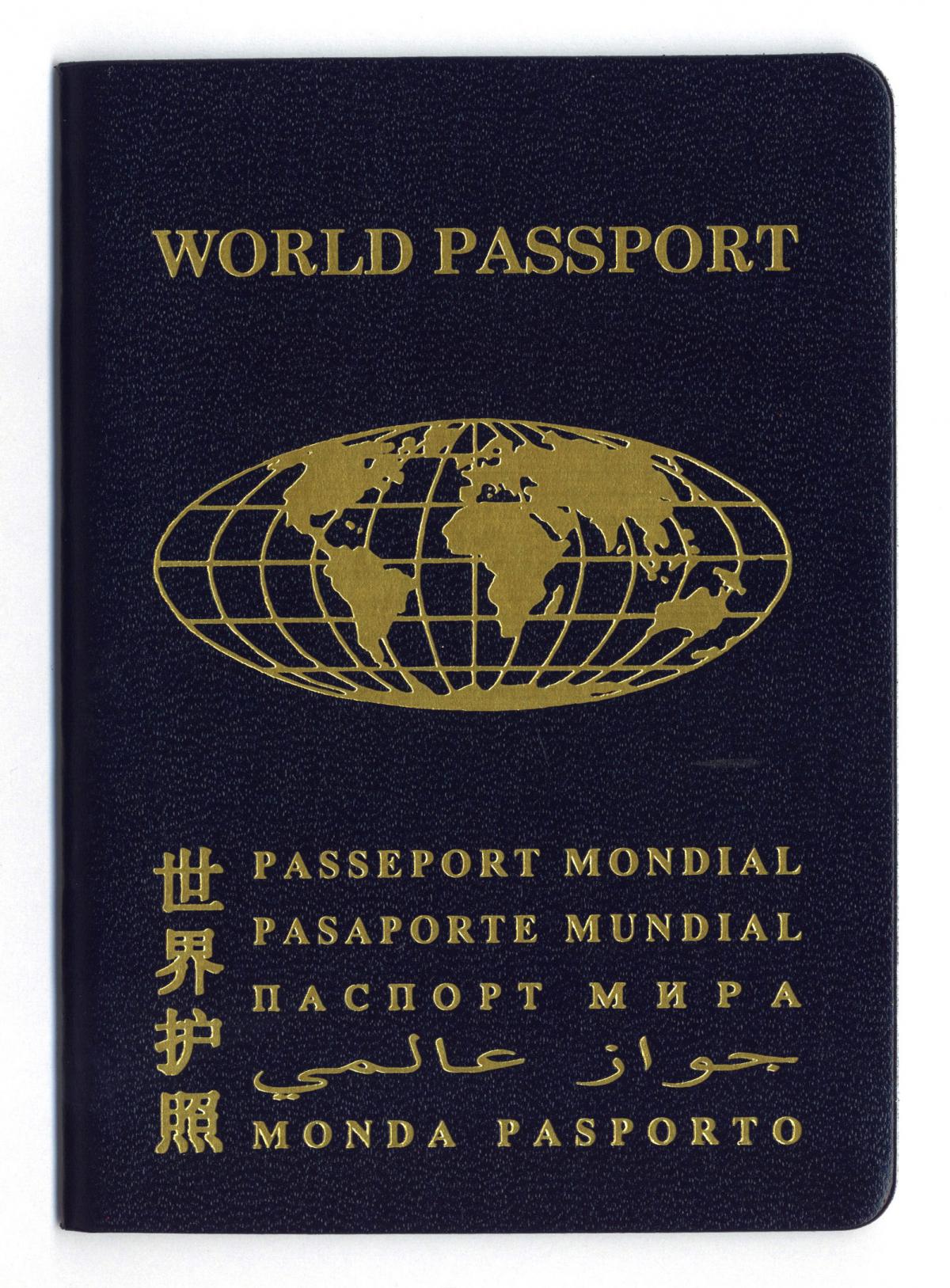

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.More than half a century later, the WGWC has issued its World Passports to hundreds of thousands of people, among them such notable personalities as Albert Camus, Albert Einstein and Richard Buckminster Fuller. A three-year passport costs US$55 (€49) and can be applied for by mail, the whole procedure taking roughly a fortnight. The passport itself looks, for lack of a better word, stately, and true to its title, contains text in English, French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic, Chinese and Esperanto.

Scan of the World Passport granted to the author. The passport was requested online, paid for by credit card and delivered by courier within a few days. According to the accompanying documents, appearances make a difference and individuals are recommended to be courteous, respectful, presentable and well groomed. The World Service Authority has issued more than four million documents, and claims that the passport is accepted in Burkina Faso, Ecuador, Mauritania, Tanzania, Togo and Zambia. (Photo: Peter Biľak)

Issuing a passport, however, is hardly the same thing as gaining the formal recognition of the nations of the world. During his lifetime Davis was arrested at least 32 times while trying to use a World Passport to enter various countries including Japan, France, Canada and Russia. He made his first attempt at the Indian border in 1956, dressed in a homemade uniform and carrying a passport he had printed himself. Since he eventually managed to get in, India is the first of the more than 100 nations claimed by the WGWC to have acknowledged its passport although Burkina Faso, Ecuador, Mauritania, Tanzania, Togo and Zambia are the only countries listed as having officially done so. The rest of the list consists of countries where confused or incompetent border officials thought letting a traveller enter was the fastest solution to a problem they could not handle, and to this day it is difficult to say where and when the passport will work.

Garry Davis’ idealism was backed by a great sense of theatrical expressiveness. Davis worked as a Broadway stage actor, and although he often argued his way out of precarious situations, he was also arrested dozens of times for attempting to enter countries without official papers, carrying only a passport of his own design.

The WGWC considers this merely a minor delay in a grander plan. ‘The passport is one of our means to a bigger end, world peace,’ explains David Gallup, president of the WGWC, speaking from its headquarters in Washington, DC. ‘This will be achieved by establishing a fully functioning world government with institutions such as a World Parliament and a World Court of Human Rights, and with a World Currency based on energy spent and CO₂ emissions, an idea first proposed by Buckminster Fuller.’ As for existing institutions like the United Nations and the International Court of Justice, ‘these institutions are restricted by the veto right of the powerful states or limited funding. A world government is truly democratic and represents all the people.’

None of these institutions of the WGWC have yet been realised, but Gallup remains hopeful. ‘According to the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer all revolutionary ideas must pass three stages: ridicule, opposition and finally acceptance.’ So far the World Government seems stuck in the phase of ridicule, ‘but opposition is growing,’ says Gallup.

In 1949, Garry Davis was allowed to fly from France to Belgium without a passport or any other papers, the first per- son to do this legally. He was allowed to stay in Belgium for 24 hours to address a meeting of his fol- lowers. (Photo: Planet News Archive)

The fact that few people take the WGWC seriously may be partially attributed to Garry Davis himself, since the organisation was not only his brainchild, but also more or less a one-man show. As much a performer as an activist, he was known for border tactics that drew as much on his theatre experience as on his idealism: dress immaculately, speak articulately, have all the paperwork neatly in order, move up the chain of command as quickly as possible and most importantly, show determination. Well into his sixties, for example, he landed at Tokyo’s Narita Airport, where he argued with the border officials who refused him entry, appealed to the Minister of Justice, was detained overnight and placed on a return flight, got himself thrown off the plane, escaped from detention the next day, and immediately went downtown to do interviews at a Japanese daily newspaper. Recaptured, he was escorted back to Seattle by two armed private security guards, where immigration officials were confronted by a conundrum: the US had classified him as an ‘excludable alien’ in 1977, making it impossible for him to enter the country, as Davis made clear in a promptly issued press release. Border crossings, however, were far from his only activities. He also ran for mayor of Washington, DC in 1986 (receiving 585 votes), and also ran for President of the World in several self-organised elections. Quips such as ‘The World Passport is a joke—but so are all other passports’ did nothing to convince sceptics of the viability of his project.

For a short moment after the fall of the iron curtain it looked as if a wind of change was blowing. ‘The first passport of Vytautas Landbergis, the first president of the newly created state of Lithuania, in 1991 was a World Passport,’ says Gallup. ‘At that time we had a yearly revenue of over a million dollars.’ Today that sum is a meagre US$300,000 (€268,000). Still, Gallup considers the current migrant crisis to be a reflection of the need for the WGWC to carry on. ‘The real problem is not the number of refugees but the absence of a functional government and basic human rights in large parts of the world, a situation that could have been prevented with a functioning world government.’ He admits that valid World Passports would not entirely solve this problem, but says that they ‘would provide at least a proof of identity and a minimum of human rights to these stateless people.’

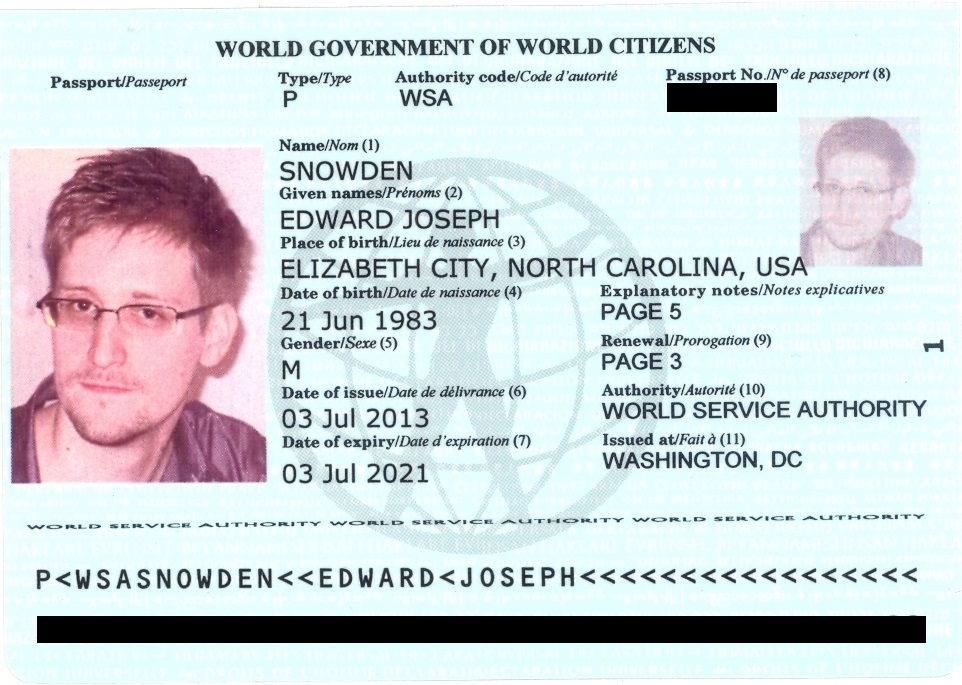

In 2013, WGWC issued a World Passport to Edward Snowden, a document that he has never received. (Image courtesy of World Government of World Citizens.)

The last time that the WGWC rose to such an occasion, however, was in July 2013 when whistleblower Edward J. Snowden was stranded at a Moscow airport because his US passport had been revoked. Davis immediately issued a World Passport to Snowden, his last official act. A week later the champion of a unified mankind died at the age of 91 years. Snowden, trapped between two powerful nations, never received the passport.