Colour Photography Before Colour Photography

Colour photographs taken over a hundred years ago using a primitive, long-abandoned process which produces spectacular images.

Cover photo: At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky (1863–1944) used a special colour photography process to create a visual record of the Russian Empire. Some of his photographs date from about 1905, but the bulk of his work is from between 1909 and 1915, when with the support of Tsar Nicholas II and the Ministry of Transportation, he undertook extended trips through many different parts of the empire. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)

Colour photography came into its own in the 1970s when adequately sensitive films finally became affordable for amateur photographers, the result of more than a hundred years of effort by a long series of scientists and hobbyists trying to push imaging technology past black and white. Probably the earliest experiments with three-colour separations were made in the 1860s by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who established the theoretical foundations for colour perception but was unable to develop a process for accurate colour reproduction.

In 1908, the Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky took the first colour photo in Russia, a photo of novelist Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. The fame of this photo led to an audience with Tsar Nicholas II, who commissioned Prokudin-Gorskii to document the Russian Empire and granted him special access to its restricted areas. He travelled with a small team in a specially equipped railway carriage photographing churches, monasteries and emerging industries, as well as the daily life and work of Russia’s diverse population. Over the course of ten years, his collection grew to number over 10,000 photos.

The photographs are remarkably engaging, not only for their extraordinary documentation of pre-revolution Russia, but also for their vivid colours and stunning quality. To this day, nobody knows exactly what camera Prokudin-Gorsky used, as no documentation of his equipment is known to exist, but it was likely a large wooden camera with a special holder for a sliding glass negative plate, taking three sequential monochrome photographs, each through a different coloured filter. Although such cameras were commercially available, it is also possible that Prokudin-Gorsky, the holder of a patent for a simultaneous-exposure camera, built his own, as well as the three-colour projection system used to display his work.

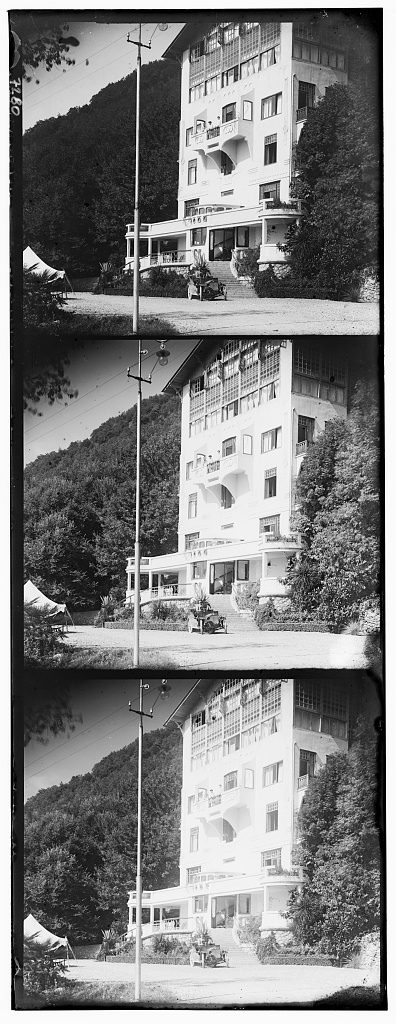

In the spring of 1912, Prokudin-Gorsky went to photograph the Caucasus region, including the resort of Gagra in Abkhazia, located in the northern part of Georgia and on the coast of the Black Sea. In 1864, Abkhazia had been formally annexed by the Russian Empire. At the turn of the 20th century, Prince Aleksandr Petrovich Oldenburgsky invested heavily in the northeast coast of the Black Sea to turn the area—which had spectacular scenery—into a Russian Riviera. Its subtropical climate made Gagra a popular health resort in both Tsarist and Soviet times. Seen here is the main entrance to the Gagra hotel; construction on this building began around 1902. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)

The image shows three monochrome diapositive images taken with Prokudin-Gorsky’s camera. They were taken one after another through a red, green and blue filter respectively. Prokudin-Gorsky also designed an ingenious light-projection system which combined the three images on a screen resulting in a full-colour picture.

Sequential-exposure cameras were used mainly for landscape photography (or very patient still subjects), as they required lengthy exposures and two repositionings of the camera’s plate holder. The quality and resolution of these photos made over 100 years ago is exceptional even by today’s standards.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The Library of Congress, which acquired the collection, digitised the glass plates in 2000 and subsequently commissioned composite colour images, bringing Prokudin-Gorsky’s images to viewers in the digital age.

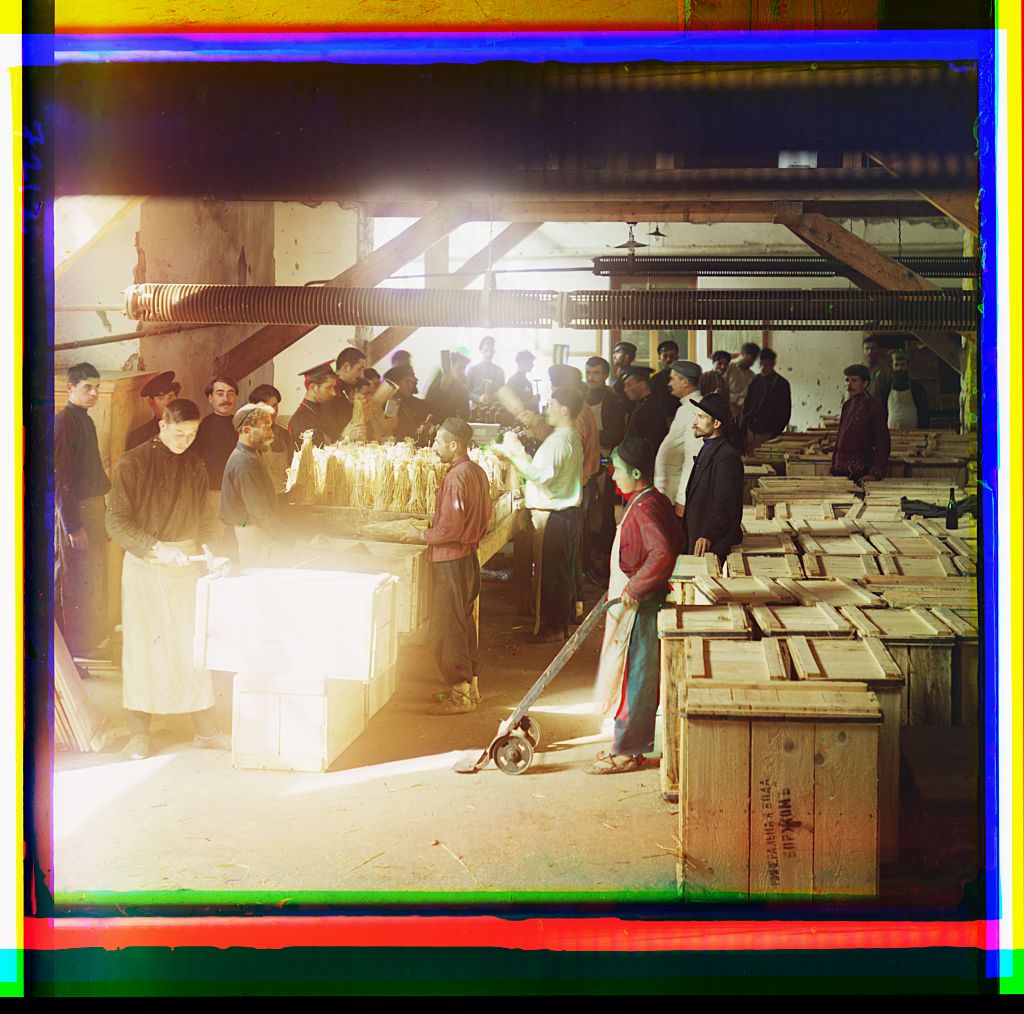

Workers taking a break in the packaging department of a mineral water warehouse in Borzhom, a resort town in south-central Georgia. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)

Said Mir Mohammed Alim Khan (1880–1944), the last emir of Bukhara, in a portrait taken in 1911. The Emirate of Bukhara became a Russian protectorate in 1868, and was overthrown by the Red Army in 1920. Alim Khan went into exile and eventually settled in Kabul, Afghanistan. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)

Prokudin-Gorsky’s photo process involved taking three successive monochrome photographs, each through a different coloured filter. This photo is flooded with yellow because the blue glass negative was broken, revealing the inner workings of the technique. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)

A peasant family at the end of a harvest day by their sheaves of rye. The exact location of this image is not specified, although the position of this photograph in Prokudin-Gorsky’s album of contact prints suggests that the photo was taken along the Sheksna or Vytegra Rivers within the Mariinsk Waterway System linking St Petersburg with the Volga River basin and now known as the Volga–Baltic Waterway. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorsky Collection.)