Weapons of Mass Deception

What use is an inflatable dummy tank in a very real war? A lot, if the enemy believes that it’s real. The men of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops knew that their lives and the lives of thousands of others depended on tricks and tactics that often had to be improvised on the spot.

Cover photo: Inflatable dummy tanks and trucks set up near the Rhine River in Germany. Attention to detail was critical. Bulldozers were used to make tank tracks leading up to where the 93 lb (42 kg) inflatable dummies stood. Real artillery shells were tossed around fake guns. ‘We wanted to create the natural debris that goes with faking something’ said veteran Jack Masey. (Photo courtesy of the US National Archives.)

Imagine being assigned to create a massive trompe l’oeil, and not just a painting, but a complex, 3-D, multimedia installation spread out over many kilometres. Imagine that it must convince an attentive and discerning audience to believe in and interact with something that is not really there. Further imagine that your workspace is in the middle of a war zone, and that thousands of lives depend on your success. Also, imagine that next week you will be asked to do it again. That, in a nutshell, was the mission given to the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, also known as the Ghost Army, one of the most unusual units to serve in the United States Army during the Second World War. Included in its ranks were art students, sound engineers and Hollywood writers, and its ultimate goal was to use creativity, performance, and sleight of hand to save lives and help win the war.

By late 1943, the Second World War had been going on for four years, easily the biggest and most calamitous event in the history of humankind. Now the Allies were preparing an invasion of Europe that they hoped would be a devastating blow to Hitler’s Third Reich, but they understood that defeating the German Army would be a Herculean task and sought to give the attacking troops every possible advantage. Impressed by tactical British deception efforts in North Africa, they brainstormed how best to equip American armies with a deception capability.

A Ghost Army trooper paints an inflatable rubber tank modelled on an M-4 Sherman. The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, an elite force whose speciality was tactical deception, was a matter of military secrecy until its declassification in 1996. (Photo courtesy of The US National Archives.)

Military deception is as old as war itself, but the idea the Allied planners came up with represented something new: a mobile, self-contained deception unit capable of staging multimedia illusions on demand. The 1,100 men in the unit were capable of simulating two full divisions—up to 30,000 men—with all the tanks and artillery that the real units might be expected to have. The illusion might discourage the enemy from exploiting a weak spot by making the site seem as if it was heavily defended, or could draw enemy troops away from where real American units were planning an attack.

Formed in January of 1944, and sent into action after D-Day, the Ghost Army went to war armed with three types of deception to fool the enemy: visual, sonic and radio. Visual deception was handled by the 603rd Camouflage Engineering Battalion. Originally formed to carry out large-scale camouflage, it was loaded with young artists, architects and designers who now turned their visual talents to a different kind of art. Many of them went on to become famous, among them minimalist painter Ellsworth Kelly, fashion designer Bill Blass, wildlife artist Arthur Singer, and photographer Art Kane. They were young unknowns at the time, working with their comrades to create convincing tableaus that could fool enemy reconnaissance planes.

The Second World War has been the subject of countless books and movies, but only recently has information about this audacious and highly imaginative top-secret army unit been made public. Using dummy equipment, theatrical special effects and acting skills, they impersonated other US Army units to deceive the enemy.

To this purpose, they were equipped with hundreds of inflatable tanks, cannons, trucks, and even aeroplanes that could be used to create dummy tank formations, motor pools, and artillery batteries that looked like the real thing from the air. These decoys were not simply giant balloons, but consisted of a skeleton of inflatable tubes covered with rubberised canvas, an ingenious design which ensured that a single piece of shrapnel could not instantly deflate the entire dummy.

Working with inflatable tanks certainly had its quirky moments. Corporal Arthur Shilstone recalled being on guard duty one day when he halted two Frenchmen on bicycles who accidentally wandered past the perimeter. ‘They weren’t looking at me, they were looking over my shoulder. And what they thought they saw was four GIs picking up a 40-ton Sherman tank and turning it around.’ Searching for an explanation, Shilstone finally told them, ‘The Americans are very strong.’

To complete the experience, the Ghost Army also used sonic deception, helped by engineers from Bell Labs. The team recorded sounds of various units onto a series of sound-effects records, each up to 30 minutes long. The sounds were recorded on state-of-the-art equipment, and then played back with powerful amplifiers and speakers that could be heard 15 miles (24 km) away. Wind speed and direction had to be factored in, so the army created a mobile weather station to accompany the sonic unit. (Photo courtesy of the US National Archives.)

Sonic deception was carried out by the 3132 Signal Service Company. With the help of engineers from Bell Labs, they painstakingly recorded the sounds of armoured and infantry units onto a series of sound effects records that they brought to Europe. For each deception, the appropriate sounds were selected to create the needed sonic scenario, perhaps the sounds of a tank brigade moving up a hill, or soldiers digging in at night. These sounds were mixed onto state-of-the-art wire recorders (the predecessor to the tape recorder), and played back over powerful speakers that could be heard 15 miles (24 km) away. ‘We could crank the speakers up on the back of the half-track [a vehicle with wheels in front and caterpillar tracks in back] and play a program to the enemy all night, of us bringing equipment into the scene,’ recalled veteran John Walker. ‘We could make them believe that we were coming in with an armoured division.’

Radio deception was the job of the Signal Company, Special. A handpicked crew of highly skilled radio operators created phoney traffic nets, impersonating radio operators from real units. They learned the art of mimicking a telegraph operator’s style so that the enemy would never catch on that the real unit and its radio operator were long gone.

The three types of deception were used in concert so that each reinforced the others. All the men were told that they had to consider themselves part of a travelling roadshow ready to perform at a moment’s notice. One week they might pretend to be the 75th Infantry Division, the next the 9th Armored Division. ‘We must remember that we are playing to a very critical and attentive radio, ground, and aerial audience,’ Ghost Army commander Colonel Harry Reeder explained to his officers. ‘They must all be convinced.’

The 23rd crossed over from England to France a few weeks after D-Day and conducted initial small-scale operations amid the hedgerows of Normandy. Moving through the French villages so recently occupied by the Germans, they saw an opportunity to improvise yet another way to sell their deceptions, targeting enemy spies that might have stayed behind. The idea bubbled up from the ranks and was eventually approved by the brass. They called it ‘special effects’ or ‘atmospherics’.

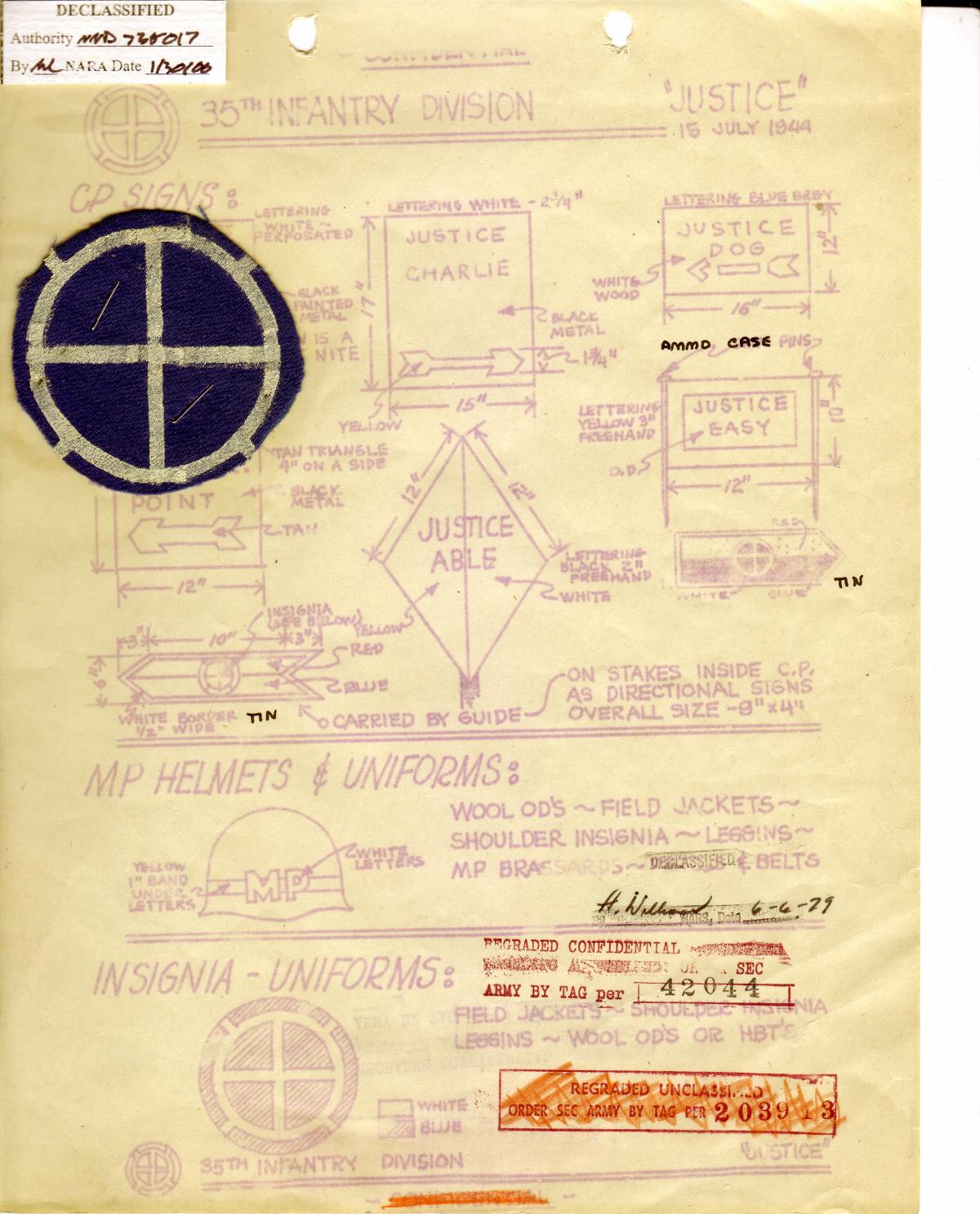

It was, in essence, a form of performance art designed to lend an extra degree of realism to their productions. They altered their uniforms and vehicle markings to those of whatever unit they were imitating that week. They drove their vehicles back and forth through local towns to create the illusion of heavy traffic. They visited cafés and spun fictitious stories for whatever spies lurked in the shadows. ‘We were turned loose in town,’ said John Jarvie, a corporal in the camouflage unit who went on to a career as an art director, ‘and told to go to the pub, order some omelettes, and talk loose.’ They even went so far as to create fake command posts, and against all Army regulations staffed them with counterfeit commanders. A colourful mission critique written by a young lieutenant named Frederick Fox (who went on to become a Protestant minister and a White House aide) explained why such rule breaking was necessary. ‘Impersonation is our racket. If we can’t do a complete job, we might as well give up. You can’t portray a woman if bosoms are forbidden.’

The Ghost Army unit simulated actual units deployed elsewhere by painting appropriate unit insignia on vehicles and creating patches for the different units they were impersonating. Soldiers wearing the patches of the unit being impersonated would appear, spilling phoney stories at cafés and other places where enemy agents were likely to see them. Corporal Jack Masey recalled that his shirts were wrecked because he had sewn so many patches onto them. (Photo courtesy of the US National Archives.)

Each Army division had a distinctive shoulder patch. To accurately impersonate the men of the 5th Armored, for instance, the deceivers had to wear 5th Armored patches. But deceptions had to be organised quickly in response to developments on the battlefield, and there wasn’t always time to obtain the necessary patches. A dozen men were assigned to the ‘factory section’ where they cranked out counterfeit patches made of tent canvas. One of the soldiers, Seymour Nussenbaum, recently estimated that they manufactured 40,000 of them during the war.

The United States Army entered the war without much in the way of deception tactics. ‘There were no manuals, no instructions, no guidance,’ wrote operations officer Colonel Clifford Simenson years later. In essence, the men of the unit had to learn their craft themselves, and do it under battlefield conditions. The unit’s first full-scale operation came in August 1944 when the French port city of Brest was under siege by the Allies, but still tenaciously held by German paratroopers. Three American divisions were assigned to take the city. The mission of the 23rd was to inflate the apparent size of the American forces by impersonating the 6th Armored Division in the hopes that it would help convince German General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke to surrender. They were also trying to attract German anti-tank attention to the flanks to help clear the way for a possible American attack in the centre.

The unit divided into three fake, or, in military parlance, ’notional’, task forces. Two of them simulated tank battalions. Radio trucks were set up along the road from Normandy to Brest to set the stage for the deception by mimicking a large convoy traversing Brittany. At just the right moment, sound trucks pulled up to within 500 yards (460 m) of German lines to make it seem as if armoured units were arriving and making camp. More than fifty dummy tanks were set up, along with dummy jeeps and trucks. Camouflage nets were strung up, and the dummy tanks were supplemented with a handful of actual light tanks placed in the most visible positions. The men lit fires, pitched tents, and even hung laundry in the area where the fake tanks were set up to make the illusion complete.

Many of the soldiers of the Ghost Army were artists, architects, or set designers recruited from New York and Philadelphia art schools and encouraged to use their talents and imagination in a theatre of quite a different kind. It is estimated that their multimedia show saved many thousands of lives. Several of these soldier-artists went on to have a major impact on art, the most prominent probably being Ellsworth Kelly.

Sergeant Bob Tompkins could see German observers keeping watch from a distant church tower, so he and the other men of the 603rd couldn’t just set up their dummies and walk away; they had to be ever watchful, especially in the hours before dawn. ‘During the night, the gun turrets would sag, and that’s a bad visual effect the next morning.’ Nor was the mission without danger, as the Germans could hardly be expected to let the arrival of the ‘6th Armored’ go unchallenged, and the men keeping vigil dug in to protect themselves against the frequent German shelling.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Special effects were ramped up as well; 6th Armored patches and vehicle markings were hastily created and applied. GIs from other units who heard the sounds of tanks moving in during the night were delighted the next morning to see soldiers who were apparently from the 6th. ‘We pulled into that area,’ said Jarvie, ‘and the guys said, “they’re bringing heavy tanks in here, just what we need.” And they came running and said, “Boy are we happy to see you guys.”’ Security considerations prevented Ghost Army soldiers from telling them the truth.

The third notional task force set up a phantom artillery unit. Dummy artillery pieces were set up about 600 yards (550 m) in front of the 37th Field Artillery Battalion. Flash canisters consisting of artillery shell casings filled with half a pint (0.25 ℓ) of black powder were used to simulate firing at night. Telephone lines were run between the real artillery and the Ghost Army’s fake batteries to synchronise the canister flashes with the real firing. The impostors operated for three nights and received 20 to 25 rounds of enemy fire, while the real artillery received none.

In many ways the deception was a success. Intelligence officers reported that the Germans shifted from 20 to 50 artillery pieces to meet what they evidently believed to be a major armoured threat. After the fall of Brest, captured German officers told interrogators they believed that the 6th Armored had really been there, when in fact it had been just the illusionists of the Ghost Army. But the deception did not achieve the goal of bluffing Ramcke into an early surrender. He and his men fought on for four more weeks. Furthermore, in the minds of most Ghost Army veterans any success they could claim was overshadowed by the deadly consequences of an American attack mistakenly launched right from where the Ghost Army was attracting German attention.

The 1,100-strong Ghost Army would usually impersonate a specific, much larger division, such as the 6th Armored Division, which had 15,000–20,000 soldiers. This photo shows a mock-up of an artillery piece typically used to support large divisions. (Photo courtesy of the US National Archives.)

General Troy Middleton, the American commander at Brest, had ordered a general attack on the Germans to take place on August 25. Due to a lack of communication, or perhaps a failure to appreciate the impact of the deception, one company of light tanks moved in on the Germans from precisely the area where the Ghost Army had been simulating a tank battalion. German anti-tank weapons, drawn by the deception, opened fire on the real American tanks. ‘Those guys never reached the line of departure,’ recalled Jarvie. ‘They just got decimated.’

The incident weighed heavily on the men. Decades later, Jarvie remained haunted by the fact that the GIs manning those tanks undoubtedly thought the heavier tanks of the 6th Armored would be there to support them. ‘We had no way of knowing they were going to kick off an attack,’ said Jarvie, ‘and they had no way of knowing that we weren’t going to help them. And it makes you feel lousy.’

Brest was a learning experience for the Ghost Army, a chance to rehearse before a live audience, to see what worked and, more importantly, what didn’t. A few weeks later, in their next deception, they would need to use what they had learned to carry off what may have been their riskiest mission of the war, holding a vulnerable spot in the line for General George Patton.

After sweeping out of Brittany, Patton’s Third Army raced across France, all the way to the Moselle River and the border with Germany, stopping only when fuel ran low and German resistance stiffened. Patton massed his troops for an attack on the fortified city of Metz, leaving a dangerous gap to the north, with as few as 800 men covering one stretch of 20 miles (32 km). ‘If the Germans realised that there were effectively no troops in the 70 mile (113 km)-wide stretch, they could have broken through easily,’ said military historian Jonathan Gawne. ‘They could have surrounded Patton at Metz to the south. This was a very severe risk.’ The mission of the 23rd was to plug the hole in the line by once again pretending to be the 6th Armored Division, which was still working its way east.

They drove 250 miles (400 km) from Paris across France and Luxembourg. On the night of September 15 they pulled in near the town of Bettembourg, just south of Luxembourg City. They were apprehensive about being just a few kilometres from the front, with very few fighting troops around. After a few hours of fitful sleep, they leaped into their newest role the next morning.

An inflated rubber L-5 reconnaissance plane used by the Ghost Army at one of the last operations on the western border of Germany. Their last performance, Operation Viersen, successfully fooled German forces into converging to defend a point on the Rhine miles away from the actual attack. (Photo courtesy of the US National Archives.)

Allied air superiority was limiting German aerial reconnaissance, so they adjusted their technique, setting up only 23 dummy tanks, relying more on radio, sonic, and special effects to carry out the deception. With the Germans just across the Moselle, sonic deception was particularly crucial. Sonic trucks operated for four straight nights. Sergeant Victor Dowd heard ‘enormous sounds of tracks racing through the forest, sounded like a whole division was amassing. Loudspeakers blaring, sergeants’ voices yelling, “Put out that goddamned cigarette now.” It was all fakery—it was all a big act.’

Numerous special effects were staged. The men received a cursory briefing on the 6th Armored before being sent into nearby towns, supposedly on recreation leave, where they could be overheard talking about their division in cafés and bars. Ghost Army soldiers guarded intersections dressed as Military Police from the 6th Armored. In one especially brazen special effects ploy, a three-jeep convoy with 6th Armored markings pulled up to a tavern run by a suspected Nazi collaborator. Out stepped the division’s commanding general and his aide (actually two officers from the 23rd in disguise), accompanied by menacing bodyguards with machine guns. The group ‘liberated’ six cases of fine wine, loading them onto the general’s jeep. The little convoy then took off, giving the seething proprietor plenty of incentive to get word to the Germans about what he thought he had just witnessed: the American 6th Armored Division moving into what was in reality a thinly held area.

Operation Bettembourg was originally only supposed to last for two days, until the 83rd Infantry Division could arrive to fill the hole. But the 83rd was delayed, so the deception stretched out day after perilous day. Every passing hour increased the odds that the Germans might see through the ruse. The enemy, which had retreated across France in disarray, was regrouping and becoming more aggressive. German patrols of 20 men or more were crossing the river, probing American lines. Civilians reported seeing Germans in nearby woods. Telephone wires laid by the Signal Company were found cut. The mood grew tense. As Lieutenant Bob Conrad put it, there was nothing between the Ghost Army and the Germans ‘but our hopes and prayers’.

To pull off this deception, the Ghost Army used tanks, jeeps, and artillery all made from inflatable rubber. For the charade to be believable, soldiers in the Ghost Army had to pay extreme attention to detail. An inflatable tank might look real enough on the ground from a distance, but aerial reconnaissance could reveal a conspicuous lack of tank tracks, so a bulldozer was used to make fake tracks around the fake tanks. There was one cardinal rule about working with inflatables: never carry one across a road or in any other place where you could be seen. Obviously, two men carrying a 40-ton tank would be a dead giveaway.

Even General Patton was feeling the pressure. He commented on the situation (without mentioning the Ghost Army) in a letter to his wife. ‘There is one rather bad spot in my line, but I don’t think the Huns know it. By tomorrow night I will have it plugged. [The 3rd Cavalry] is holding it now by the grace of God and a lot of guts.’ The very next day the 83rd Division arrived on the scene, and the men of the Ghost Army gladly relinquished that part of the line.

Operation Bettembourg was the Ghost Army’s longest deception of the war. The 23rd’s Operations Officer, Colonel Clifford Simenson, considered it a turning point for the unit. ‘It was our first operation that was executed fully professionally and correctly.’ Now they felt they had proved their value beyond a doubt.

The 23rd went on to carry out 18 more deception operations over the course of the war, drawing on the techniques they had perfected in Operations Brest and Bettembourg. During the Battle of the Ardennes they helped draw German attention away from the effort to relieve Bastogne. And as the war neared its end, they put on a dazzling deception along the Rhine River, their biggest ever, that drew the enemy away from a real crossing by the Ninth Army.

Deception is carried out by all armies. During the Second World War, the Germans made particularly good use of it in disguising their build-up during the Battle of the Ardennes. But there is nothing to suggest that the German Army, or any army in any war, had a unit like this one: mobile, multimedia, dedicated to battlefield deception and capable of pulling it off time after time without being found out. The Ghost Army was unique.

How effective was it? ‘There are German records that show that some of the deceptions were taken hook, line and sinker,’ said Jonathan Gawne, author of Ghosts of the ETO. A United States Army analysis 30 years after the war also sings the praises of the unit. ‘Rarely, if ever, has there been a group of such a few men which had so great an influence on the outcome of a major military campaign.’

Of the 1,100 men who served in the unit, only a couple of dozen remain alive today. The Ghost Army will soon be an army of ghosts. But what they did is worth remembering. It is estimated that their deceptions saved many thousands of lives. Using only imagination and illusion, they pulled off one of war’s most difficult manoeuvres: making the enemy dance to their tune. ‘You have to see into the mind of your adversary,’ said General Wesley Clark, former Commander of NATO, remarking on the unit. ‘You have to create for him a misleading picture of the operation to come. And you have to sell it to him with confidence. It’s the highest kind of creativity in the art of war.’