The Cobbler Who Conquered the World

Tomáš Baťa built the world’s largest shoe manufacturing enterprise out of a tiny family workshop by using production methods and management techniques that were revolutionary in his era, and which still find application today.

Cover photo: A customer being assisted by the saleswoman in the Baťa store in Prague. By 1928, thanks to Tomáš Baťa’s drive and vision, Czechoslovakia was the biggest shoe exporter in the world. (Photo courtesy of Museum of Southeast Moravia in Zlín.)

When Tomáš Baťa boarded his personal plane on July 12, 1932, he was at the peak of his powers, a handsome, square-jawed man of 56 with a thick head of hair. From his headquarters in the Czech city of Zlín, he oversaw a worldwide manufacturing operation producing more than 35 million pairs of shoes annually. There were 1,825 Baťa outlets in Czechoslovakia alone, with another 660 across the globe. There were Baťa shops from Sweden to Syria, Baťa factories from Switzerland to Singapore, all bearing the same red cursive logo, and all run by the same methods and philosophy. Baťa sold affordable, fashionable, well-made footwear at a time when good shoes were luxury items.

The Baťa empire had also diversified extensively from its core business in the years since 1894, when Tomáš Baťa opened his first shoe workshop with his two siblings on Zlín’s town square. Now there were Baťa tanneries, Baťa engineering works, Baťa rubber plants, Baťa chemical refineries, Baťa power stations, Baťa coal mines, even a Baťa film studio. Baťa made bicycles and car tyres, gas masks and children’s toys. Everything was produced in highly automated, purpose-built, red-brick factories that employed 30,000 people in Czechoslovakia and thousands more abroad.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.These workers enjoyed a standard of living that was the envy of the nation. The company provided housing, healthcare, insurance, education, leisure activities and entertainment—often in breathtakingly modern facilities equipped with the latest high-tech gadgets. Baťa operated railway lines, dug canals, and even built its own airport at Otrokovice, just down the road from the Baťa company headquarters in Zlín (where Tomáš Baťa was mayor).

In an age when social entrepreneurship was unheard of, Tomáš Baťa built not only factories, but also homes, schools and hospitals for his workers… …as well as the most successful shoe store chain of his day.

It was here, just before six AM on a foggy summer morning, that the industrialist climbed into his Junkers two-seater, keen to get underway after being delayed at the airfield for two hours. His personal pilot had urged him to linger a few minutes more to allow the fog to lift, but Baťa’s 17-year-old son Tomáš Jr. was waiting anxiously in Zurich. Later that day father and son were to open the newest addition to the Baťa empire, a 24-hectare (59-acre) complex in the Swiss town of Möhlin. For reasons that are still unclear, Baťa’s plane crashed a few minutes after take-off and broke into three pieces. He and his pilot were killed instantly. His funeral two days later was attended by 150,000 people. The factory sirens of Zlín wailed in mournful tribute.

The economic crisis of the 1920s severely affected Europe, especially Germany and the neighbouring countries; however, Baťa Shoes was expanding due to ballooning demand for its inexpensive shoes. Zlín, home of Baťa’s headquarters, became a prosperous hypermodern city and manufacturing centre. Facilities included not only plants that produced textiles, rubber and plastic for socks and shoes, but also shoe polish and other chemical products. Furthermore, Baťa operated its own paper mills (to produce packaging materials), tree farms (to replenish the wood used by the paper mills), machine shops (to produce manufacturing equipment), brickyards (to build employee housing), farms (to supply subsidised food to workers and the city) and infrastructure (to transport goods and materials), as well as a coal mine and electrical plant (to power the whole operation). In 1923 the company boasted 112 branches. (Photo courtesy of Museum of Southeast Moravia in Zlín.)

‘Baťa was simply a genius,’ said Pavel Velev, director of the Tomáš Baťa Foundation, as he gave me a guided tour of the Baťas’ functionalist villa. ‘He did everything for his fellow man. His chief idea was to do things that would benefit people, his employees, his fellow citizens,’ Velev told me, opening a door into what was once Tomáš Baťa’s office. ‘Baťa didn’t just give his workers money. He gave them the opportunity to work, to live, and build a life for themselves. He was rich, but he didn’t keep his riches for himself. Everyone here in Zlín was rich; they had well-furnished houses, they had well-paid jobs, the city was here to serve them. As Baťa famously said, “Buildings are just heaps of bricks and concrete. Machines, just a lot of iron and steel. What breathes life into them is people.”’

We gaze out of the window up the hill to the red-brick factory buildings in the distance. There are anecdotes of Baťa standing at this window at the crack of dawn, making urgent early morning phone calls to his employees: ‘Nováček! Why’s there so much steam coming out of Building 3?!’; ‘Topol! What are those pallets still doing outside Building 4?!’ He was, it seems, a man of relentless vigour with an eye for perfection. And the doctrine he developed over the course of his life was visionary. Bataism was an economic and social philosophy that cherry-picked the best ideas of the early 20th century and put them into practice in a shoe factory, a globalised social business model decades before these words even entered the common lexicon.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Baťa’s internship at the Ford Motor Company in 1904 seems to have inspired his use of automated assembly lines as well as his unprecedented system of autonomous workshops, a chain of successive production units, each buying partially finished products from the previous unit, working on them, and then selling them on to the next unit in a process that continued until the shoe was finished and ready to leave the factory. This encouraged greater personal responsibility, raised standards and minimised waste.

By 1928, thanks to Baťa’s drive and vision, Czechoslovakia was the biggest shoe exporter in the world.

The salary and benefits scheme too was generous and unique in an age when other industrial giants saw workers largely as a commodity to be exploited. ‘They did some surveys in the 1920s and 1930s, and found that the average weekly cost of living in Zlín was 161 crowns. Elsewhere in Czechoslovakia it was 257 crowns. The average weekly salary of a Baťa worker was 450 crowns,’ said Velev.

Baťa employees received their wages via Baťa bank accounts earning 10% interest per year. Profits and losses were also shared in a unique motivational scheme which initially involved senior employees, but later applied to the junior ranks as well. When an autonomous unit produced good-quality work, on time and on budget, employees were rewarded with bonuses. If the workmanship was shoddy or the designs out of fashion and unsellable, salaries were docked. ‘Most people got used to the system,’ said Velev. ‘Those that didn’t left.’

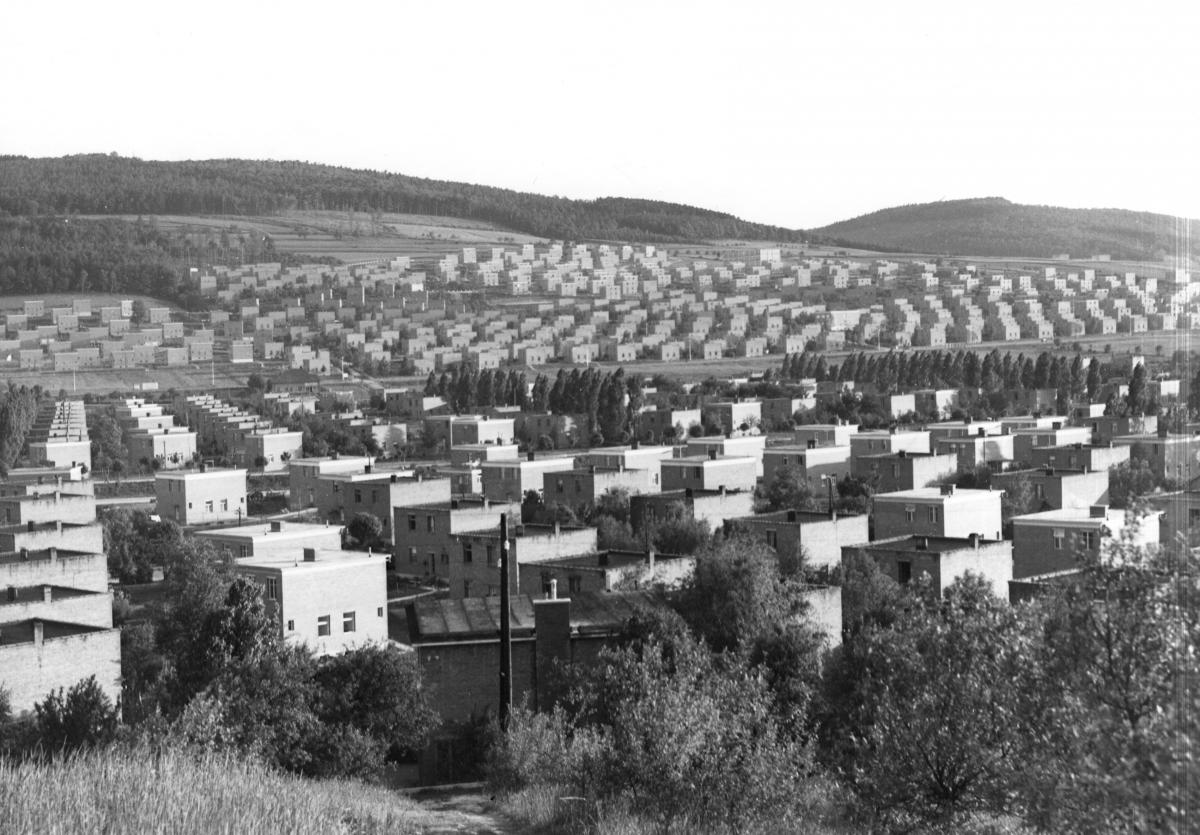

Prior to 1894, the city of Zlín had a population of 3,000. The city grew rapidly, however, as thousands of families moved to Zlín to live in the large garden districts that Baťa Shoes built for its employees. Between 1923 and 1932, their numbers grew from 1,800 to 17,000; the city population increased from 5,300 to 26,400. Zlín became one of functionalism’s greatest achievements, a living example of progressive architecture as a by-product of its construction techniques tracing its lineage to Le Corbusier’s vision of urban modernity and the Garden City proposed by Ebenezer Howard. The urban plans proved to be futuristic, featuring sustainable, low-maintenance buildings, green spaces and integrated transportation. (Photo: J. Vaňhara, courtesy of Moravian Provincial Archives in Brno, State District Archives Zlín.)

Flush with an enormous disposable income, Baťa workers spent their hard-earned cash in Baťa canteens and Baťa department stores and Baťa cinemas and Baťa swimming pools in what Velev describes as a ‘cycle of money’. Many bought their own Baťa-built homes; neat, newly built red-brick houses, each with a little garden and the latest in modern conveniences.

The Baťa system might strike the modern reader as utopian or even Orwellian, with an employer’s tentacles reaching into every aspect of the employees’ lives. And the system did have its darker overtones; an employee overheard espousing Marxist ideas on the train, for example, might find himself without a job the following morning. Workers lived according to company ‘recommendations’, tenets of Baťa philosophy that guided everything from how much money to put by to when to get married. But it’s important to place the Baťa vision into the context of an undeveloped rural region in south-east Moravia with few other prospects for gainful employment.

By 1927, Baťa Shoes had assembled a network of quality schools and well-equipped hospitals for its workers and their families, because founder Tomáš Baťa firmly believed that business should serve the public. Baťa was one of the first companies to provide social services and health care for all employees, to employ handicapped individuals as a matter of policy, and to introduce a five-day working week of 45 hours. (Photo: Petrůj, courtesy of Moravian Provincial Archives in Brno, State District Archives Zlín.)

‘The work Baťa offered gave local people a chance to escape from the humiliating existence in which most of them lived,’ said Miroslava Štýbrová, a footwear historian and teacher based at the Tomáš Baťa Institute, newly opened in a renovated factory building known simply as Building 14. ‘Many of these people were shepherds, peasants; many had never even seen a big city. Overnight they were granted incredible opportunities, the chance to own their own houses, their own cars, to travel, to educate themselves. These are things that are difficult for us to comprehend today,’ she told me.

‘Baťa knew well from his time in Detroit that if he looked after his employees, if he provided job security, a social net, culture, sport—if he gave them a sense of well-being, something that most workers here at the time could only dream of—it would pay dividends in terms of both loyalty and productivity. As a result Tomáš Baťa’s employees genuinely looked up to him. It’s hard to understand today just how motivated they were. He turned them into fanatics, really, in the positive sense of the word. They were utterly committed to this joint effort, this joint work,’ Štýbrová said.

According to Velev, Tomáš Baťa’s motivation for treating his employees with fairness and respect stemmed from his own early failures. ‘I think it all goes back to his early attempts at creating a business. He suffered some cruel setbacks. And he had to overcome these crises on his own,’ he said. ‘He wasn’t a convinced capitalist from the beginning. Far from it. He was sceptical about using the new modern machinery to mass produce shoes, for example. He was worried about exploiting his workers. But when those same workers convinced him it was saving them time, that it was making their lives easier, he began to change his mind.’

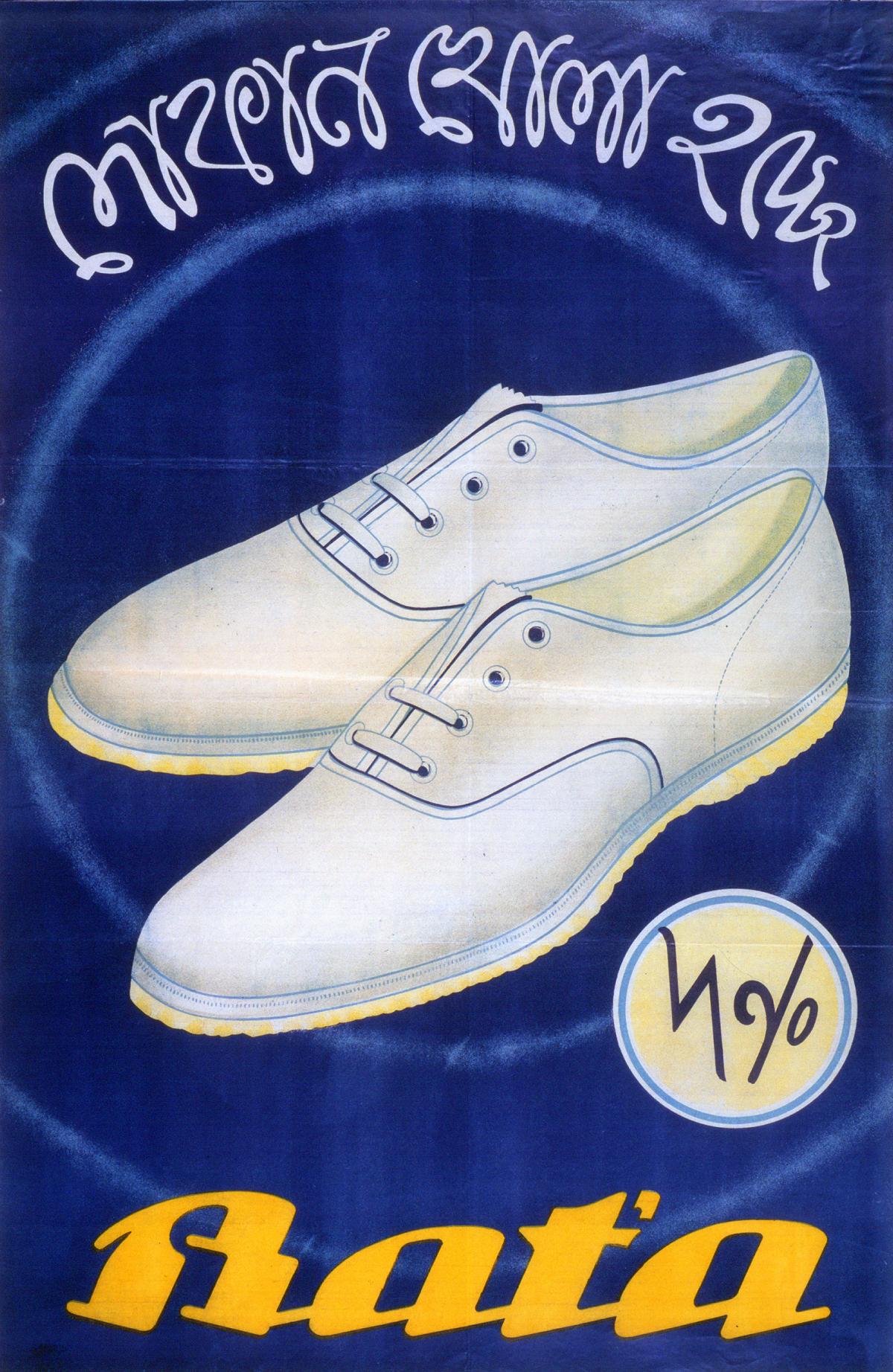

Bata advertising in India. Bengali text reads: ‘Opening shop’ (Photo courtesy of Museum of Southeast Moravia in Zlín.)

Around the world, dozens of ‘Batavilles’—Batanagar in India, Batapur in Pakistan, Batatuba in Brazil, Batawa in Canada, Batadorp in the Netherlands, Baťovany in Slovakia, Bataville in France—continued to build on the principles established by Baťa in Zlín, supplying welfare and education of customers and employees alike.

‘His primary motivation was the well-being of his employees. I think there are certainly such visionaries around today. But Baťa took it to another level. If you look at companies such as Google or Microsoft—okay, Bill Gates has given a lot of money to charity, he supports education and so on. But he never built houses for his employees, or cinemas or swimming pools. Baťa’s vision was far more ambitious.’

A group of young Egyptians in the ‘Baťa School of Work’. As the company grew, it built factories and towns across the world, in the US, Canada, India, France, the Netherlands, Brazil and Britain, all based on Zlín’s universal system. This Professional School of Footwear, a government-approved institution, educated thousands of young men and women of the company, providing rigorous professional training and social education, but also teaching foreign languages, music and household management. (Photo: J. Vaňhara, courtesy of Moravian Provincial Archives in Brno, State District Archives Zlín.)

Word spread quickly about ‘the miracle of Zlín’. In 1925, when Baťa opened his new School of Work, a specialised shoemaking school to train 1,500 apprentices, there were 10,000 applicants. They came not just from Czechoslovakia, but from Britain, France, Yugoslavia, Egypt and India.

Baťa relied on an unprecedented egalitarian training scheme for new employees, regardless of seniority. Apprentice shoemakers, middle managers, and designers all had to spend a number of weeks learning the business from the ground up, from tannery to showroom. It even became customary for wealthy entrepreneurs and politicians to send their privileged children to spend a month at Baťa to observe how a successful business functioned.

‘For some of them, such as Otto Wichterle, the Czech chemist who later invented the contact lens, this was a bit of a shock,’ explained Štýbrová. ‘Wichterle came here with his brother shortly after finishing university. They were from a rich family and arrived by car. Wichterle later wrote in his memoirs that they were expecting their own fancy offices, maybe with a secretary. Instead they were each given a broom and sent to sweep up scraps of leather in the tannery.

‘By performing all tasks of the workmen I discovered methods that led to the saving of materials and even simplifying of the workmen’s labour…’ —Tomáš Baťa

‘The idea was for future managers to understand what hard physical work meant, the hard physical work done by people who one day would be their employees. And equally, humble cobblers or shop assistants were given a taste of senior management and told that they too could rise through the ranks.’

‘It was a very good system,’ she added.

Factories and workers’ houses were laid out along generous boulevards as the city struggled to keep up with the company’s relentless expansion. When the renowned French architect Le Corbusier visited Zlín in 1939 he described it as an ‘incredible example of an industrialised city’. Not for nothing was it nicknamed ‘America in Czechoslovakia’. Sadly, the Nazi occupation of the Second World War and the subsequent rise of communism proved as devastating to the Baťa empire as to the country in general.

Zlín, the original Bataville, had its own company cinemas, restaurants, sports facilities, garages, farms, grocers, butchers, post offices, newspaper and, of course, shoe shops. In short, it was just like every other city except that everything was owned by Baťa. The danger was that an entire town was dependent on the fortunes of one company. Several of the Central Euro- pean Batavilles—Baťovany (present-day Partizánske), Baťov (now Bahňák, part of Otrokovice), and Zlín itself—were dev- astated by the communist regime, and later by the transition to a free-market economy. (Photo courtesy of Museum of Southeast Moravia in Zlín.)

Renamed ‘Svit’ (‘Glow’) after the Second World War, the shoe factory suffered heavily from four decades of communist central planning. Even the city of Zlín was renamed, becoming Gottwaldov in 1949, in honour of Czechoslovakia’s ‘first working-class president’, and the Baťa name quickly became taboo. Today there is still life in these ‘heaps of bricks and concrete’, but it’s a different kind of life: sleepy, almost listless. Zlín is now a student city with little industry and certainly no shoe production.

Shortly after the Velvet Revolution, Tomáš Baťa’s son Thomas Bata (he discarded the diacritics after emigrating to Canada) stood on the same terrace, surveying the city his father had built. But it was with mixed feelings. Later, in one of the abandoned factory buildings, he stumbled across the very machine on which he had stitched together his first shoe in 1932, the year his father died. Plans to revitalise the giant plant after the collapse of the communist regime slowly fell by the wayside. The brick buildings and machines and conveyor belts were still there. But the burning entrepreneurial spirit had gone.