The Reality of the Fake

Modern technology and the commercialisation of art raise difficult questions. If someone takes a professional picture of a painting, who is the artist and whose is the art? And what if someone makes a professional painting of a photograph?

Cover photo: In this tiny quiet suburb of Shenzhen, just north of Hong Kong an estimated 5,000 artists used to produce up to 60 percent of the total global volume of reproduction artworks until the the 2012 economic crisis changed the market, and workshops began to focus on creating original works for Chinese customers. (Photo: Antonio Pisacreta)

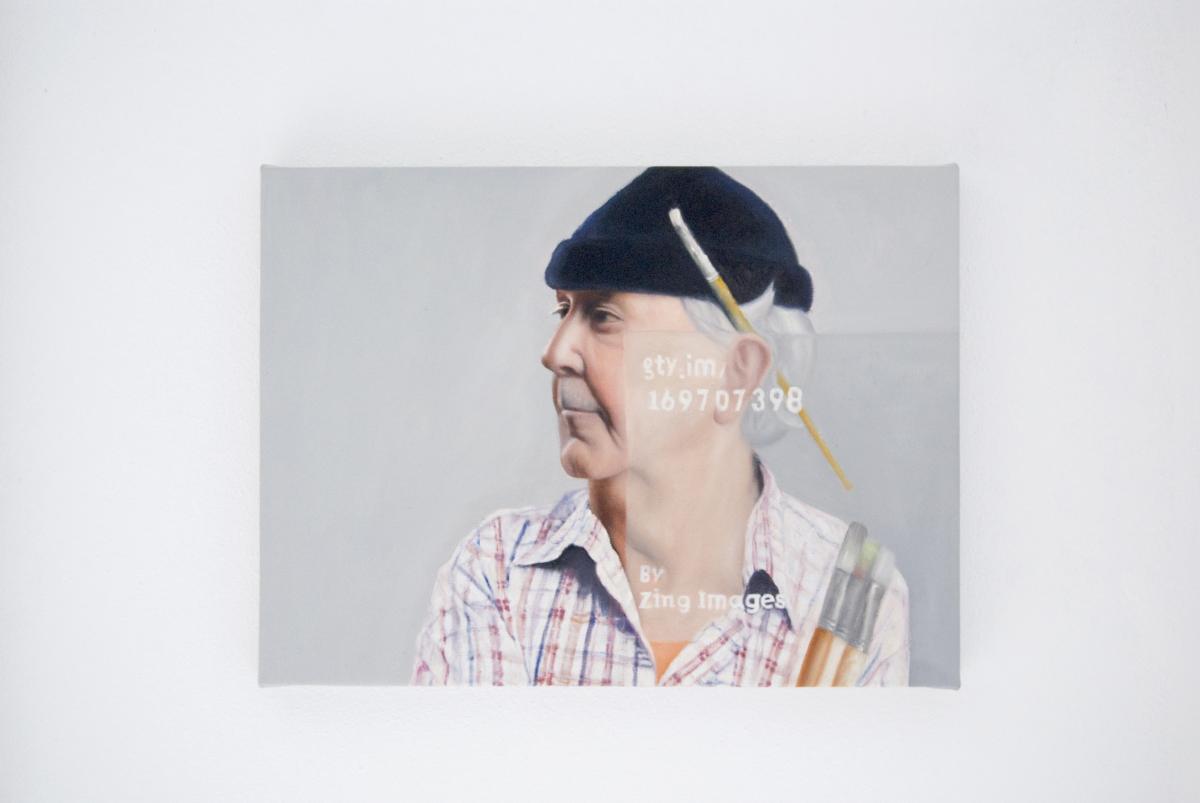

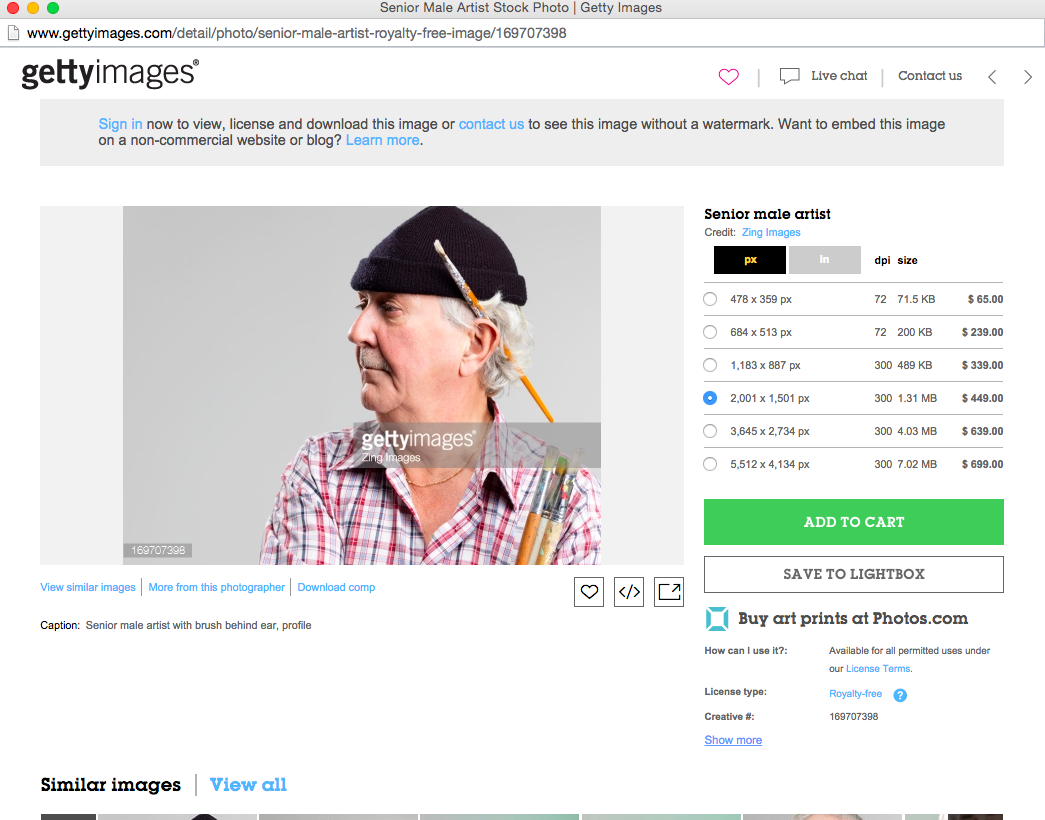

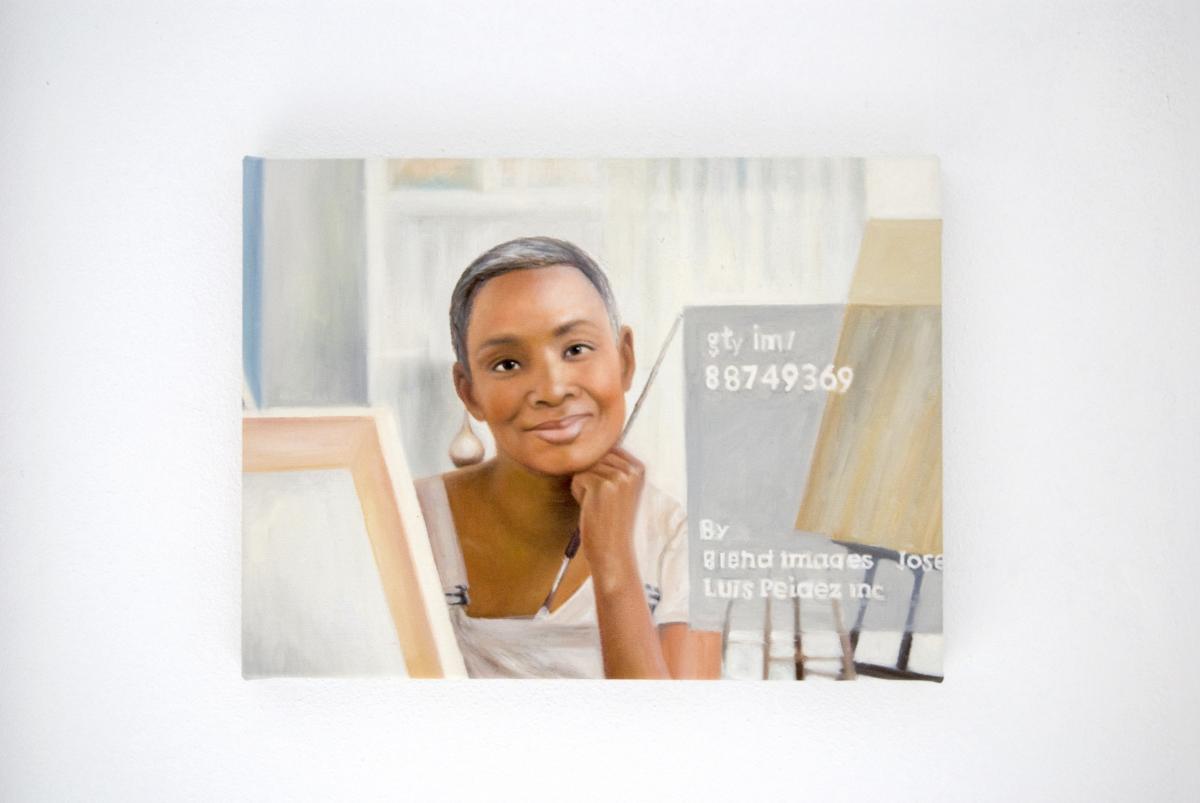

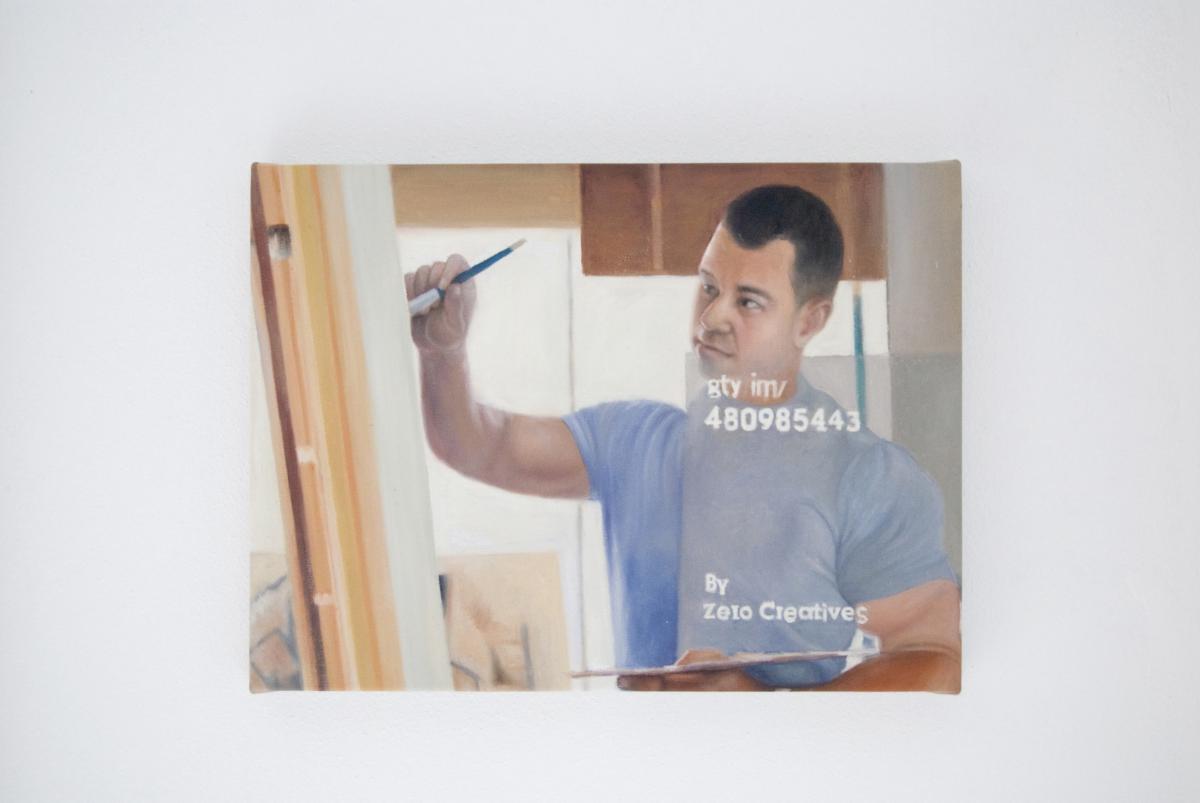

Six small paintings in Udine, Italy were intended to raise some big questions. Inspired in part by the way that typical stock photos grossly misrepresent artists and the artistic process, IOCOSE searched the archive of the well-known licensing agency Getty Images for pictures matching the keyword ‘artist’, and downloaded six thumbnails, complete with their serial numbers and watermarks. The group then sought painters to recreate the thumbnails as oil paintings.

They turned to Dafen Artist Village, a suburb of the coastal city of Shenzhen, China, widely known as the largest supplier of hand-painted canvases in the world, where a freshly painted Van Gogh can be had for as little as €26.50 (US$30). ‘The choice was made based on the price/speed/quality ratio. As you can see, it’s not that different from buying any other product or service,’ explains IOCOSE member Paolo Ruffino. ‘We found them via Google.’

‘A single painting is art. If you produce it in large quantities, it’s an industry,’ says 36-year-old artist-cum-factory-chief Wu Ruiqiu.

The result, titled ‘A Contemporary Portrait of the Internet Artist’, is a set of IOCOSE-commissioned oil painting copies of digital thumbnails of stock photos of assorted models posing as stereotypical painters. It is a convoluted collaboration of artists made thinkable only by this era of global electronic communication, one which challenges the idea of authorship as we commonly understand it. When each of the contributors had a critical role to play, but all are unknown to each other and most have never even met, who is the author, and whose is the image? Is it the photographer’s, the art director’s, the licensing agency’s, the painter’s or IOCOSE’s?

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.‘The responsibility for assembling the chain of workers and collaborators was ours from the beginning, but the question of whether we are the authors of the project is precisely the point here. We are the artists collecting the work of others and “moving it around”, if you like,’ says Ruffino. ‘We don’t even know the names of the models or of the painters involved.’

To create ‘A Contemporary Portrait of the Internet Artist’, the art collective IOCOSE searched Getty Images, supplier of 80 million digital pictures, and selected six photos tagged with the keyword ‘artist’. They downloaded watermarked thumbnails of pictures that retail for €42–659 (US$45–699), then contacted Chinese art reproduction websites to negotiate prices and delivery dates. The final oil paintings are for sale for €1,000 each (US$1,061), or €5,000 (US$5,304) for the whole series.

Those anonymous artists collaborating with IOCOSE from the other side of the world belong to the legion of painters that constitutes the world’s largest concentration of artists per capita. The more than 2,000 workers in the 4 sq. km (1.5 sq. mi) gated community supply 60% of the world’s oil paintings, according to China Daily. During the village’s founding years in the early 1990s, the American megastore Walmart placed an order for 55,000 reproductions in 45 days.

To meet the high demand, studios had to streamline procedures fast. Some employ a factory-style assembly line where painters work on a section of a painting, then pass the canvas down to the next artist in the chain. Some studios specialise in a particular artist’s oeuvre or in a specific style. Techniques and best practices are codified and passed on to the new workers coming from one of the village’s art academies.

In her book, Van Gogh on Demand, art historian Winnie Wong distils the recipe for a Vincent Van Gogh classic after weeks of apprenticeship in Dafen with Zhao Xiaoyong, a painter who specialises in the works of the 19th-century Dutch artist:

How to Paint Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (F. 457)

Tack a blank canvas of the required size onto the drawing board.

Tape down a one-inch border around the canvas with masking tape. This leaves the necessary space to stretch the canvas onto wooden strainers later.

Tack up another Sunflowers painting from the shop for reference.

Mix quick-dry medium into the titanium white.

Prepare the palette with large amounts of lemon yellow, medium yellow, cadmium red orange and titanium white, smaller amounts of rose madder, burnt sienna, forest green, and cerulean blue.

Using leftover dirty paint anywhere in the yellow-to-red spectrum, sketch out the overall composition. Start with assigning the location of the vase’s opening, the edge of the table, and then outline the shape of the vase. Draw six ovals with smaller inner circles where the six round sunflower blossoms should be. Mark out the ovals of the other flower blossoms, and the dried leaves near the vase.

Paint the first layer of the background: using a ¼ in (0.6 cm) brush, lightly combine two dabs titanium white and one dab lemon yellow. Make sure not to mix the two pigments together too much, and to leave traces of pure pigment in the mixture. Load this onto the brush. In a ‘井’-character pattern (that is, two horizontal lines followed by two vertical lines), fill in the background. Work lightly. Do not pull too hard or the effect of each thick brushstroke will be lost. Be sure that each brushstroke is visible. Be light and at ease. Do not grip the brush tightly. Remember to keep loading pure pigment onto the brush.

After the whole background is painted, use a ⅛ in (0.3 cm) brush to paint over the whole background again with the same two pigments and the ‘井’-character pattern, this time loading more paint onto the brush with every stroke. Make it brighter in the centre, darker at the edges of the painting.

Repeat the same two-layer process with the table, using long horizontal strokes. This time use equal amounts of lemon yellow and medium yellow on the ¼ in brush. Add in a few green strokes for depth.

Paint the upper part of the vase using medium yellow and cadmium red orange, mixing in some burnt sienna and rose where needed. Paint the lower part with lemon yellow, medium yellow, and white. Remember to paint the vase as a rounded volume.

With the same brush, pick up amounts of light yellow and medium yellow, fill in the large blossoms in very short strokes, turning each stroke towards the centre of the blossom. Add darker yellows as necessary to round out the volume of the blossoms.

Taking a palette knife, pick up equal amounts of two yellow pigments with the back tip of the knife. Dab or dot the paint in a circular pattern with light strokes pulling outward from the centre of each blossom. Progressively add darker yellows, orange, and sienna in order to round out each blossom. Work lightly and don’t scrape into the wet paint.

With the ⅛ in brush, paint in the blossom petals in profile.

Using a third ⅛ in brush, load with dark green pigment and freehand draw each leaf. Make it look natural, like a leaf.

Using the same brush, fill in the centre of each flower with three strokes of green, sienna, and a dab of cerulean blue.

Using the same brush, but adding a trace of lemon yellow, paint in the stems.

Using the palette knife, dab white highlights on the vase, drag yellow highlights onto the green leaves, dab white highlights on buds. Using the ⅛ in brush with dark dirty paint on it, use the dirty paint on the palette and mix in dark green to get an off-black, then outline some of the vase, table, some leaves, and some blossoms.

Sign ‘Vincent’.

Hang to dry.

Repeat.

The ability of Wong’s teacher, Zhao Xiaoyong, to replicate a Van Gogh in 30 minutes has been well documented. He claims to have sold 70,000 copies of Van Gogh’s paintings over his career, at prices ranging from 200 to 1,500 yuan (€28–211 or US$32–240).

Some scholars, including Wong, would like to divert the world’s attention from the copyist trade to a broader appreciation of the artists in the village who create original works of art. But events such as the annual Dafen Copying Contest where hundreds of painters compete to create the best replica of a masterpiece only strengthen its position as the world’s copycat capital. The creation of the Dafen Intellectual Property Working Station and the practice of at least ostensible gallery inspections also attest to the problem of copyright violations.

According to Chinese copyright law, reproductions such as those produced in Dafen Artist Village are legal only if the original artist has been dead for more than 50 years. Authorities investigate and punish violations, but admit that illegal counterfeits continue to abound.

Questions of copyright and ownership aside, however, Dafen poses deeper questions: what is art, and what is it worth? For a Van Gogh lover who can’t afford an original, is it better to own a good copy than nothing at all? Is it absurd to pay millions of dollars for a painting, and who decides which paintings are worth millions? How much of a painting’s worth is in the image itself, and how much is branding? Particularly in the case of Sunflowers, what is an original and what is a copy, when Van Gogh himself painted a number of versions using different colours (and Paul Gaugin painted Van Gogh’s painting Sunflowers)? If a darker background matches the living room better (all in a day’s work in Dafen), is it still a Van Gogh? What about a purple background? Is a photograph of a painting a truer copy than a painting? And since Dafen’s ‘painter workers’ are not working from actual originals, what about a painting of a photograph of a painting?

One thing is clear: as the IOCOSE exhibition demonstrates, an efficient production model—art made mechanical—results in low prices: downloading the original images from Getty, had they paid for the licences, would have cost more than the hand-painted portraits they commissioned. The same is true of the Van Gogh. Comparing the original work valued at millions of dollars at auction, the licensed digital photograph of the painting, and the replica from Dafen, the handmade oil painting from China is clearly the cheapest alternative. What you hang in your living room is up to you.