The Forgery Market

In Manila there is a place where you can custom order forgeries of nearly any official document you desire. You can get an Oxford diploma, a Canadian driving licence or an American MD and a prescription pad. It’s cheap and fast, although somewhat dangerous and, of course, illegal.

Cover photo: Claro M. Recto Avenue is one of the principal commercial roads in north central Manila. Here document counterfeiters openly offer to create fake documents of all kinds. Among the most popular are IDs, birth certificates, marriage licences, medical certifications, fake receipts, university diplomas, driving licences and boating licences. (Photo: Renoir Amba)

Her furtive voice is nearly lost in the cacophony of the nearby traffic. ‘Do you want it to say magna or summa cum laude?’ asks the short, stocky woman with the buzz cut. ‘Are you sure this is all you want? We can do anything.’ She gestures at a thin 3 × 2 ft (1 × 0.6 m) wooden placard that has been plastered edge-to-edge with an impressive assortment of official-looking papers. Though diplomas are the stock-in-trade here, transcripts, licences, passports, letters of endorsement, court papers, affidavits, seals, stamps, receipts, cheques, awards, badges, bank documents and identification cards of all sorts are also available on short order, the possibilities limited only by one’s imagination.

The prospects are as astounding as the array of papers. Who could I be? What could I be? For a moment, I consider a liquor permit, a pilot’s licence, or a Reuters press badge, and in an age of biometric scanners and genetic testing, it’s alluring to consider that one might still be able to design (or redesign) a functional identity with a few scraps of parchment and plastic.

In the end I settle on a diploma from Harvard University, a New York state driver’s licence, a Philippine birth certificate and a Pulitzer Prize.

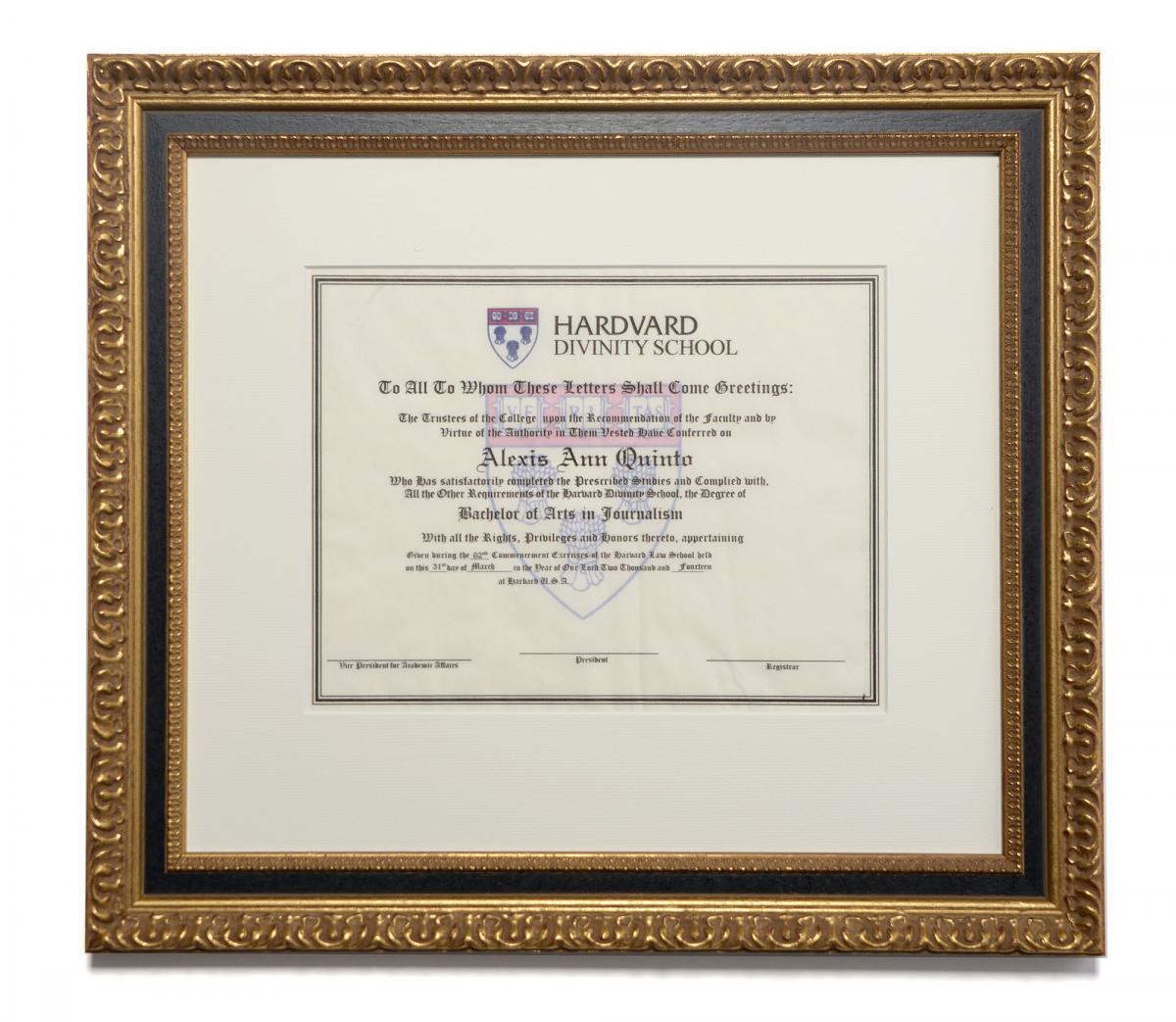

Forged diplomas produced in the streets of Manila, Philippines. The author paid 400 Philippine pesos (€8.60 or US$9.00) for the ‘Hardvard’ diploma, and 300 pesos (€6.45 or US$6.80) for the Pulitzer Prize, plus 150 pesos (€3.25 or US$3.40) for the research fee, since no original was supplied. The documents were shipped to the Netherlands, where they were framed at the local art store for €192 (US$200).

‘Write the name you want printed here,’ she mutters, her words nearly inaudible under the jeepney and pedestrian noise. As we finalise the deal, a small group of bystanders gathers around her like gadflies. She tries to shoo them off while dashing off a brief text on an battered mobile phone. ‘Meet me back here tomorrow, but you can pay me half now,’ she says, before taking the money and disappearing into the crowd.

I am in Manila, the Philippines, in a dubious and sometimes ominous district called Recto where one can order virtually any type of official document to spec. Named after Claro M. Recto, esteemed Philippine statesman and poet, the district commonly referred to as ‘Recto U’ sprang up adjacent to the capital city’s university belt in the 1960s, filling the demand for black-market term papers and fake report cards. The operation, reportedly run by a local syndicate, has expanded to specialise in a whole spectrum of spurious credentials, both local and foreign.

There is nothing false about the grim atmosphere that pervades Recto even at high noon. It’s the kind of place where people wear their backpacks in front and hurry to get wherever they are going as quickly as they can.

There are numerous forgery vendors along Recto and on the adjoining streets, nameless pop-up document stations wedged between street vendors that peddle pirated movies, replica ArmaLite guns, and brightly coloured dildos. For illegal enterprises, these stalls are remarkably easy to spot, each with a stool, a small desk and a brazen wooden sign advertising counterfeit goods in broad daylight. The stalls are really dispatch centres where customers place orders with the street agents or ‘faces’, as they are sometimes called. Upon receiving an order, agents call a central number to obtain price quotes that they can mark up to boost their cuts. Afterwards they negotiate final terms with customers, then hand-deliver the slip of paper containing the specifications to a runner.

The sellers on Recto Avenue don’t do the forgeries themselves, but are connected via runners to the forgers who do the counterfeiting behind closed doors at an undisclosed location nearby. A university diploma costs P 400 (€8.60 or US$9.00), a driving licence about P 1,000 (€21.50 or US$22.60), and turnaround is about two hours. (Photo: Renoir Amba)

The counterfeits are crafted in a factory-cum-workshop nearby, produced by a stable of ‘master forgers’, computer graphics operators who research the documents and then scan, retouch, and print them using Corel Draw and Photoshop. There are also ‘golden hands’, the trained calligraphers and signature forgers whose skilful work with pen and ink is no less vital. With its suite of printers, scanners, laminators and drawing tools, Recto’s forgery workshop is much like any other graphic design studio, except perhaps for the heavy security that keeps its illegal activities safe from prying eyes in a less-than-reputable part of town. (Not even the street agents know exactly where it is. ‘It’s probably better that way,’ one of them says.)

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Why then do people venture into a bad neighbourhood to do illegal business with an organised crime syndicate? One reason is that despite the risks, it makes economic sense. For instance, obtaining a sedula (a community tax certificate that also serves as a legal form of identification) involves declaring one’s gross annual income, from which the government levies one Philippine peso (₱) for every thousand earned. But for as little as ₱5, one can buy a forgery printed on an actual official form stolen from the Bureau of Internal Revenue. With the Philippine average annual income hovering around ₱140,000 (€2,800 or US$3,160), every peso saved counts, and the money saved by opting for the counterfeit document is equivalent to at least a hearty lunch or a tall Starbucks latte. Obtaining a marriage annulment certificate here, in the last country in the world where divorce is illegal, can cost up to a quarter of a million pesos (€4,980 or US$5,640), even without factoring in the cost of missing work to attend months (sometimes years) of hearings and legal procedures. In Recto, it costs ₱225 (€4.50 or US$5.00).

Even in this age of electronic documents, our lives are shaped by coloured bits of paper at nearly every step: banknotes, product labels, prescriptions, ID cards, contracts, certificates, warranty cards, traffic tickets. Recto confronts us with the question: how much can a piece of paper document reality? How much can we afford to trust it?

Some fake document vendors have other, legitimate businesses, while oth ers hide their forgeries behind dummy business cards and stamps. Documents that can be purchased for bargain prices include fake vendor permits. Most vendors bribe police to stay out of trouble. (Photo: Renoir Amba)

Time is also a consideration, and state agencies would do well to learn from Recto’s customer-focused operation and fine-tuned efficiency. It generally takes about a week to obtain a copy of one’s diploma for employment purposes, up to two weeks to get a birth certificate from the National Statistics Office, and a full day of queues, forms, a mandatory medical examination and road test to get a driving licence from the Land Transportation Office. In Recto, all this can be ready in an hour or less.

Sometimes, however, it’s a matter of desperation. For a contingent of prospective but underqualified foreign migrant workers, buying a spurious seaman’s book or a falsified school transcript from Recto is like buying a lottery ticket with higher earnings as the prize. The Über driver taking me back to Recto to pick up my documents is another case in point. He had copies of his driving licence made so that if a policeman confiscates it (a fairly common occurrence) he can still have the real one safely stowed away, as well as several backups. ‘I can’t afford to miss work,’ he says. ‘My family depends on the cash I bring in every day.’

Recto’s customers are surprisingly diverse, however, and not all of them are attempting to evade the law. There is, for example, the young professional who ordered a duplicate of her original college diploma for her mother to frame. ‘It’s just for her wall, I figured it would be okay. It’s cheaper than getting it through my university. The craftsmanship here is really good,’ she explains, inspecting the dry-embossed seal.

I meet my agent, and we repair to a nearby noodle shop with two other agents while we wait for my documents to arrive. Her colleagues appear sceptical, warily picking at the skins of their pork buns and keeping their distance. ‘Thank you for inviting us to lunch, but I hope you’re not an undercover police spy. It always starts so innocently like this, but you never know where it’s going to lead,’ says one of them, looking me up and down, then straight in the eye.

In many ways, documents are like tickets—a paper stub that admits one to a chance of a better job, a better life, even a better life partner.

The agents have ample reason to fear. The mayor of Manila, Joseph Estrada (who incidentally served a term as president of the Philippines before being impeached and imprisoned for embezzlement) has launched a massive crackdown on the illegal document trade. Not only does the black market cheat the state of the taxes generated by legitimate transactions, it also besmirches the city’s reputation. In diplomatic circles, Recto’s reputation as a global mecca for fake papers is pervasive and pernicious. It’s not uncommon to hear of consuls in American embassies rejecting visa applications from Filipinos without even glancing at their paperwork. Does this bother the agents?

‘This is just business,’ barks the woman (‘Just call me Tess’) sitting next to me. She is the most veteran agent around the table, having been running orders steadily for nearly eight years now. ‘We have children, debts, many bills to pay,’ she says defensively. When probed about the stress of being a woman in a male-dominated trade, and a perilous one at that, she softens a little and finally loses her scowl. She shares that over the years, a certain camaraderie has been forged around Recto, a symbiotic circle that includes the police they bribe with a cut from daily transactions in exchange for their tolerance.

Before computers and Internet access became affordable, Recto-made documents were priced much higher because documents had to be made completely by hand. Business efficiency tools such as Google Image Search or a robust database of diploma templates were not available then. A simple diploma could run up to ₱10,000 (€205 or US$225) and could take days to make correctly. ‘The lettering, seals and watermarks, it was really an art back then,’ Tess recalls. ‘When it’s not busy now, I practise my calligraphy. I have a book in Gothic-style lettering,’ she says, referring to the Old English typefaces commonly used on diplomas. ‘Some jobs are easy enough that when the customer is in a hurry, I can just do it myself and earn a bit more from a deal.’

The mayor of Manila, himself a convicted embezzler, has sent swarms of undercover policemen into Recto, and ironically it is now the counterfeiters who have to discern not only true customers from officers posing as customers, but also hard-line officers posing as customers from bribable officers posing as customers.

Today, pricing for documents is a fuzzy science. The same Harvard diploma can cost ₱500 (€10 or US$11.20) in one stall and three times that at the next. According to the agents, pricing depends on several factors: the kind of document, its physical complexity, the turnaround time, their perception of the customer’s ability to pay (dress down and forgo jewellery to get the best deals) and the element of risk involved. ‘Birth certificates and sedulas are easy to make and the most popular items,’ says my agent who never revealed her name (not even a provisional one like ‘Tess’). ‘Gun permits and clearances from the National Bureau of Investigation are the trickiest and can run up to ₱5,000 (€100 or US$113) because that’s what the police are most concerned about,’ she says in an even lower voice. ‘A certificate of marriage annulment can also be quite expensive because that’s a ten-page document,’ adds Tess, citing the onerous paperwork involved. ‘Oh, there’s also the reputation of the school to consider. Of course, a Harvard diploma will be more expensive than a University of the East certificate,’ adds my agent with a sheepish grin, as if to defend the fickle pricing structure.

My agent gets a text that a runner has arrived with my documents. She disappears for a minute. When she returns, she drops a small brown envelope and tightly rolled scroll rather unceremoniously on my lap. First, I inspect the birth certificate under the table. It is a fine piece of work, perhaps the best of the lot. The background guilloché pattern, the trademark yellow-green gradient, the blue seal of the National Statistics Office, a clear bar code and a stamped signature have all been perfectly reproduced to the last detail. There’s even a notation at the top right, ‘Page 1 of 1, 1 Copy’. ‘They have templates, stamps and blank forms back there,’ beams the agent in response to my compliments.

Next, I take out the driving licence. At first glance, the substantial plastic card looks impressively authentic, with the correct layout, typographic scheme and accurate personal information just as I specified. Upon closer inspection, however, I realise that it says ‘Identification Card’ instead of ‘Driver License’, the hologram is flat, and the bar code on the reverse is smeared and misaligned.

The runners who move orders and forged papers to and from the factory sometimes work in chains like a relay team passing a baton of neatly rolled-up documents from one to the next.

I slip out the Harvard diploma. I quickly notice that the letter-sized parchment sheet has obviously been printed with a colour inkjet and that the signatures at the bottom are missing. ‘I can sign it,’ offers Tess. The major is also wrong; I wanted a degree in theology, but got a B.A. in journalism instead, and for some reason I graduated on March 31, when Harvard Law School’s spring semester was still in progress. And worst of all I seem to have got my degree from ‘Hardvard’, as my diploma declares in large capital letters.

With great anticipation, I take out the last item in my Recto sampler, my Pulitzer Prize. I’m imagining an ornate, gilded certificate with multiple seals, ribbons, maybe even large embossed lettering. After all, they did charge an extra ₱175 (€3.50 or US$4.00) research fee. But when I unfurl the parchment, what confronts me is a woefully generic letter-sized template form that anyone with Microsoft Office could output. And it seems that during our hasty exchange, there had been some misunderstanding about the nature of the prize.

‘As I said, Pulitzer is not a school. It’s a very prestigious award. I thought you researched this.’ I begin to explain my overall dissatisfaction with my documents. My agent hurriedly scrawls all over the dud certificate, crossing out the word ‘University’, while simultaneously typing a text message. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll get it fixed immediately. It will only take a few minutes. So do you want that to be a bachelor’s or a master’s degree? What do you want to do about these signatures?’ She points to the Filipino names at the bottom of the sheet. ‘Should we take them off altogether? But then it won’t look balanced.’

The two other agents are watching quietly. Then Tess offers, ‘It would have been much better if you brought a sample for them to copy. The artists can do anything as long as you provide a picture.’

The veteran agent is right. Graphic artists can reproduce and doctor any credential as long as there is something to work from. On the web, vendors such as BackAlleyPress.com, Cheaper-than-tuition.com, and PhonyDiplomas.com offer higher-quality documents with greater attention to the graphic details, better-quality paper, sharper printing and correct spelling, not to mention live customer support and money-back guarantees. Marketed as novelty items, the exceptional verisimilitude of diplomas, transcripts and certificates challenges our perceptions of what is authentic and original. I think about the array of diplomas on my doctor’s wall or the impressive collection of certifications displayed by the dentist who once botched my root canal.

What differs between these websites and the stalls in Recto is the fact that these companies, many based in the USA, will refuse to print documents that permit one to prescribe drugs (like an MD), or that may compromise public security, (like a pilot’s licence). Monitored by Homeland Security, these companies will not do business with customers from places like Cuba, Syria or North Korea (or, curiously, from Connecticut or Oregon either). In bold (albeit tiny) letters, Phony Diploma’s ‘We Don’t Print’ policy states, ‘If we have any notion that you intend to use our products against the public interest or public safety, we will refuse your order.’

The thriving illegal trade in counterfeit documents forces government agencies to create official documents with ever more advanced security features, which n turn forces forgers to use ever more advanced technology to keep up. (Photo: Renoir Amba)

Meanwhile, in the side streets of Recto, rows of etchers are making rubber stamps, engravers are crafting identification badges, and pressmen are rolling out pads of blank receipts, ready for any commission and agnostic to the buyer’s intent.

Inside the mall where I got my photo taken for the fake driving licence there is a legal quick-print shop specialising in rubber stamps, duplicate keys, laminated IDs, branded lanyards, and name badges, an array of identification and credentialing paraphernalia curiously similar to what the street agents were hawking. There is even an album of company logos such as Dunlop, Quiksilver and DHL that you can use to decorate your custom lanyard or stamp. One wonders where the border between legitimate goods and forgeries actually lies.

In this tiny shop, there are two graphic operators toiling at PCs, scrolling through layouts in Corel. I ask what they think of the fake document stalls in the area. One of them responds without looking up from the monitor. ‘I can do that too, no problem,’ she retorts. Inspecting her work displayed in gleaming glass cases, I ask where she got her design training. She stops, looks up and motions across the street with a knowing grin. ‘I got a degree from Recto U.’ She laughs, then turns back to focus on the screen and hits ‘print’ on a sheet of ID cards.