A Pound for a Pound

Brixton activists decided to fight the gentrifying influence of Big Money by creating their own local currency. Their struggle, however, pits them not just against the dollar, euro or yen, but against the global economic system and the whole concept of money itself.

In Brixton, life is lived at high volume. Evangelical preachers swap shifts with busking drummers and rock bands on the loudspeakers outside the Underground station, and music blares from nearly every shop and kiosk in the curving streets around the market, a heady mix of reggae, afrobeat and gospel.

Since the 1940s this area of southwest London has been the heart of the city’s Caribbean community, but its latter-day reputation was forged in the 1970s and 80s, when unemployment and social exclusion led to rising crime rates. Its closely packed residential streets and high-rise tower blocks became the backdrop to two infamous riots, and the area became known as a centre for gang violence and drug abuse.

If any place could have resisted the gradual creep of gentrification, it was Brixton. Today though, property prices are soaring. Around Brixton’s markets—a decade ago referred to as ‘crack superstores’—the stalls selling salt fish and plantains are flanked by hipster cafés selling single-origin coffee and sourdough flatbreads. ‘A lot of the reasons that people were talking negatively about Brixton are now positives,’ says long-time resident Tom Shakhli. ‘It’s creative, it’s vibrant. It’s got a lot of counter-cultural ideas.’

You seem to enjoy a good story

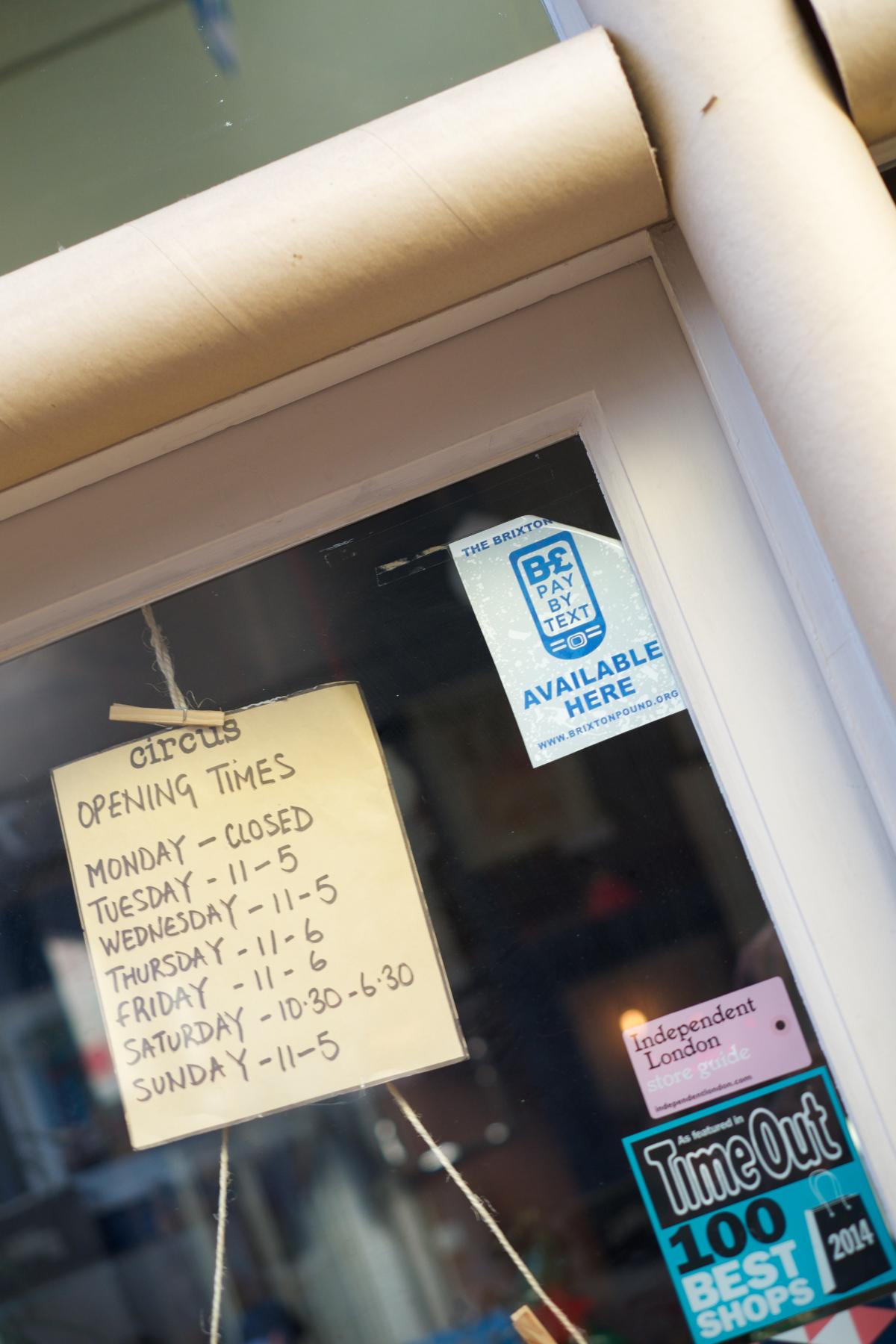

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The Brixton pound, a local currency—paper and electronic—that launched in 2009, is now accepted by hundreds of shops, bars and cafés in this multicultural area of southwest London.

The area is undergoing the traditional starving-artist-to-start-ups progression at hyperspeed, and it is pricing long-term residents out of the market. Shop rents are rising as owners cash in on the rising tide, and while the newfound affluence has washed away some of the stains on Brixton’s character, old-timers fear that it will also leach out the vibrancy and sense of community. Shops along the railway line that cuts Brixton in half are feeling this squeeze. Vendors in the railway arches have been campaigning since the start of February to stop Network Rail’s plan to evict them, renovate the spaces and then triple their rents (if it lets them return at all).

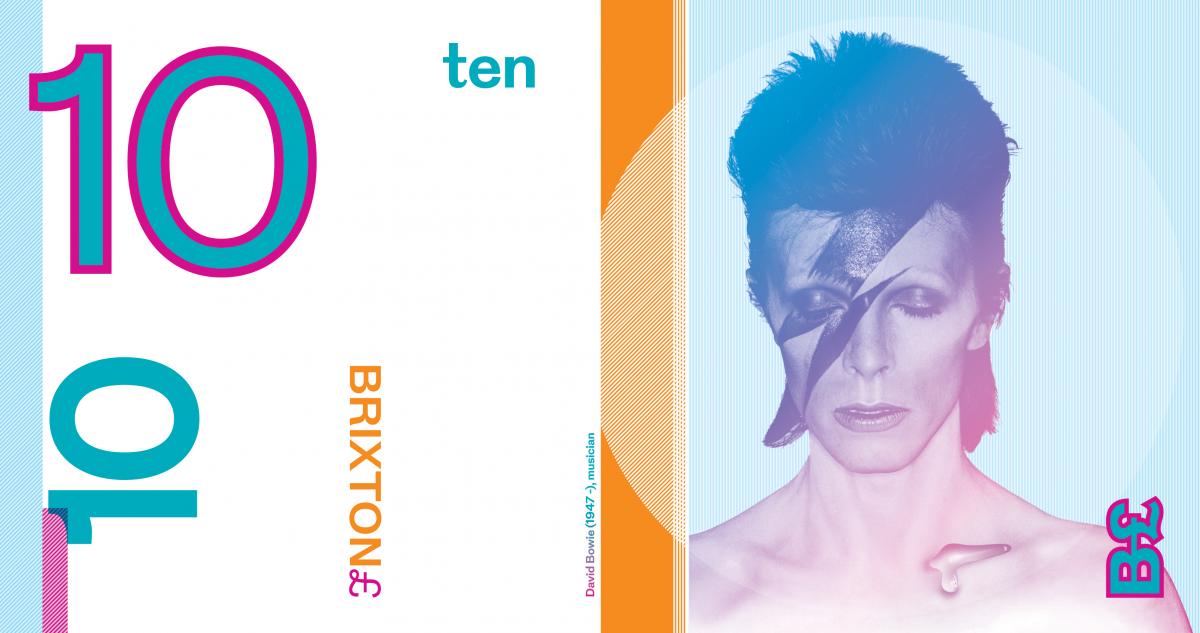

Shakhli belongs to a small band of economic activists trying to slow the flood of money and the homogenisation of the area with a radical approach: printing their own cash. Their Brixton pound (B£) notes, which feature local heroes such as basketball player Luol Deng and musician David Bowie, are accepted at approximately 250 shops, bars and cafés around the area, keeping money circulating locally, out of the hands of global chains. The project includes an electronic currency system that lets users pay using a smartphone app linked to a bank account, credit card or PayPal. Around 2,000 people have registered for the e-currency system, transacting a total of £200,000–250,000 (€269,000–336,300 or US$307,000–383,800) per year.

A straw poll of shops in the area turned up mixed support for the Brixton pound; most support the idea, but have yet to see the e-currency generate much new trade. The local council has also given the scheme its support, becoming the first in the country to allow companies to pay their property taxes in Brixton pounds, and has since estimated that the press coverage of the scheme has paid off by generating £500,000 (€672,600 or US$767,700) in positive media exposure.

The project is bigger than just a neighbourhood effort, however. Conceived in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis, the Brixton pound is, Shakhli says, a way to rethink how money is created and circulated.

‘We are trying to make people aware that money is something that we can actually try to take control of ourselves, we don’t have to leave it to the state.’—Josh Ryan-Collins, researcher on monetary reform for the New Economics Foundation

‘This is absolutely not a response to gentrification. It’s about tackling something that causes gentrification, which is the money system,’ he says. ‘We’re asking these big questions, like “What is money?” We take money for granted; we think it’s neutral, it’s like air. But it’s quite a poisonous air. There are a few people who have good gas masks who are able to survive in this system, but […] for most people it doesn’t work. It creates high house prices.’

The direct link between the monetary system and house prices in Brixton is, on one level, fairly straightforward. The financial value of London property has soared in direct response to global financial uncertainty. Turmoil in the eurozone and the devaluation of global currencies through money printing has driven investors worldwide to look for stores of value, and London real estate has proven a popular one.

The price of the average London property rose past £520,000 (€703,800 or US$799,500) in 2014. Wages have stagnated and for many Londoners, home ownership is now a distant aspiration. Once down-at-heel areas are being redeveloped with an eye on the international market, made over with concrete and glass edifices that are gazetted to portfolio buyers in the Middle East and Asia before they go onto the local market.

There is a deeper link, however, that runs to the core of how money and monetary systems function. The vast majority of money is created not by governments and central banks, but by the private sector, in the form of loans to investors, businesses and consumers.

‘They lend for speculative house buying, which increases demand, which pushes prices up. People think of property prices as a supply issue, that you need to build more houses, but actually there’s a massive problem of pumping the markets with demand,’ Shakhli says, adding, ‘This is not a crackpot theory.’

The Brixton pound (B£) was launched in September 2009 as a physical, paperbased currency, and expanded in September 2011 to an electronic payby text platform. Around 250 businesses currently accept B£ notes and over 160 have payby text accounts. Each denomination of the paper banknotes commemorates a local hero (selected by popular vote by the people of Brixton), celebrating their history, art, politics and culture. The B£10 notes show David Bowie, who lived in Brixton from 1947 to 1953.

The Brixton pound is just one of many attempts to offer an alternative to the predominant monetary systems. In the UK the city of Bristol and smaller towns such as Totnes and Lewes operate their own currencies. In Germany there are more than 50 such projects. Each has its own purpose, from building marketing networks for local small businesses to building in carbon credits and supporting environmental projects. Each is empowered by the sense that money itself can have an objective.

In the words of Leander Bindewald, a researcher in complementary currencies at the New Economics Foundation, ‘Money is not neutral. When you ask an economist or consult a textbook, they just give you these three functions: store of value, means of exchange, unit of account, but never go further to ask what would be the most convincing way to do all three? Can you do all three at once? Are there inherent conflicts in achieving one or the other better?’

These are questions that are rarely asked, but which have huge relevance in a global economy that is increasingly defined by inequalities between those who own assets and those who do not. Indeed, in a financial system inextricably linked with the environmentally unsustainable use of resources, answering these questions correctly may be a matter of life and death.

Local charities can choose to accept donations in B£. Donors who are registered for the electronic currency system can contribute by text message to causes from soup kitchens and food banks to energy conservation initiatives and immigrant services. In addition, 1.5% of all electronic transactions goes to fund micro-grants for area projects.

‘The money you use predetermines the outcomes in an economy or a society. Finding the right kind of money for the objective is what community currencies are trying from the bottom up. But there’s also a top-down argument in monetary reform saying we have to tackle money as a question, as a thing in itself,’ Bindewald says.

Shakhli knows that small-scale approaches like the Brixton pound are not going to paper over the cracks of a system that is failing many. They are, however, raising awareness that there are alternatives and fixing some of the symptoms.

‘It’s an experiment, as much as anything else. It’s not something that we see as being the answer, as such, but it gives people the idea that money can be plural,’ he says. ‘Exchanging using Brixton pounds can create a social connection in a way that using a pound sterling doesn’t. The pound sterling is a very passive connection; I just chuck some money at you. When you use the Brixton pound you’re much more likely to make a connection with the business owner. You are actively doing something different. You’re expressing your values.’