Tower of David: Urban Survival Creativity

Some saw the occupation of the abandoned skyscraper as a legitimate solution to Venezuela’s economic paradox of ‘people without homes and homes without people’. Others saw it as the world’s tallest slum. In any case, turning the empty, unfinished building into a liveable space required perseverance and ingenuity.

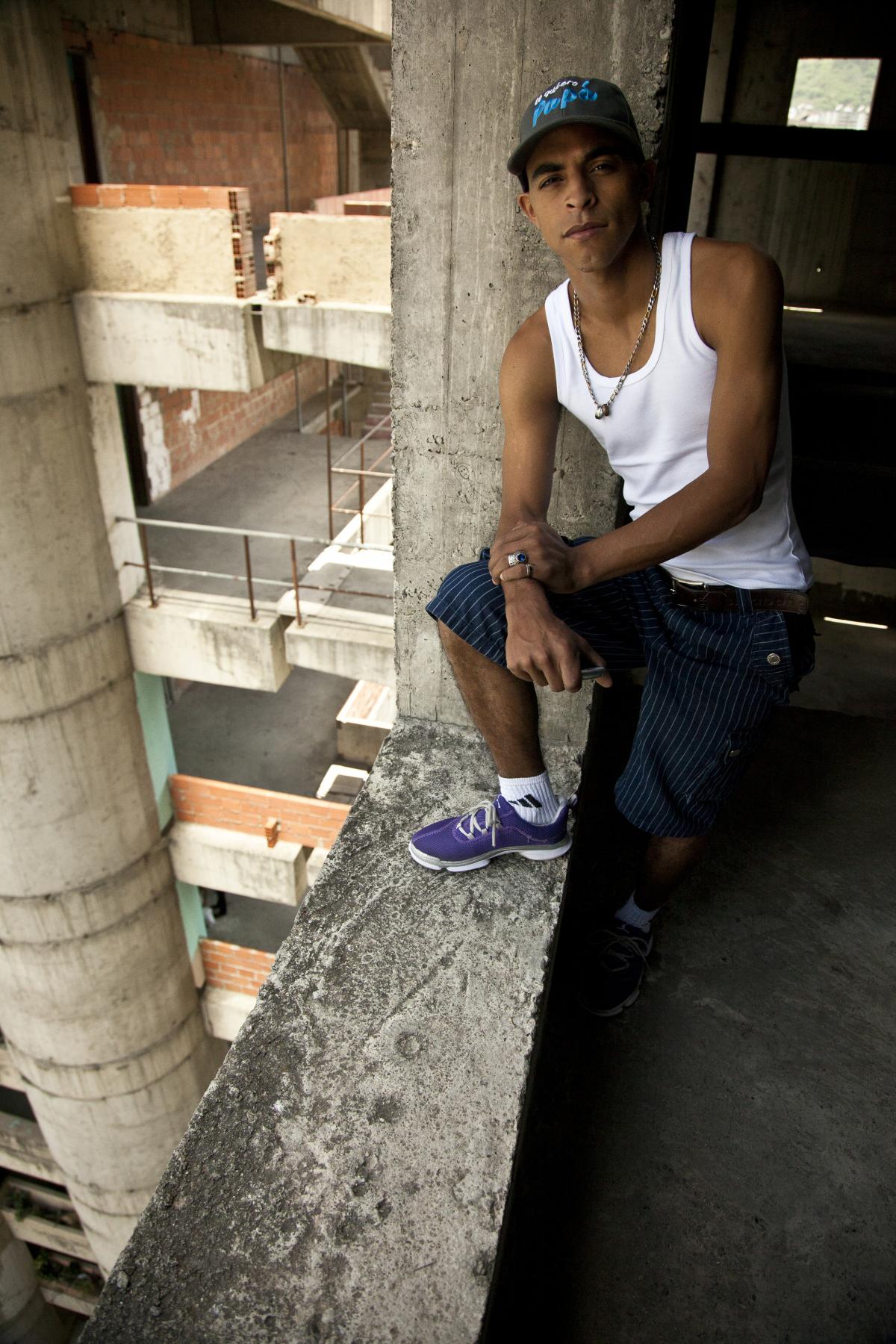

Cover photo: During an oil boom in the 1950s and 1960s Caracas grew in economic importance. Viewed as one of Latin America’s most modern cities, it underwent explosive development, attracting thousands of rural migrants seeking new economic opportunities. Housing failed to keep pace with the rapidly increasing population, and by the 1990s more than half of the city's population lived in slums. Controversial Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez urged the poor to occupy ‘unused’ land, prompting squats to spring up in abandoned buildings across the country. (Photo by Iwan Baan)

Hipólito lives in a comfortable apartment on the 17th storey of the Torre de David, an enormous abandoned skyscraper complex in the centre of Caracas, Venezuela, a place widely known—and feared—as ‘the world’s tallest slum’.

Simon Rafael La Rosa has been living on the 22nd floor of Torre de David for five years, along with his wife, son and dog. Like many of the tower residents, he is politically active, a committed supporter of the late Hugo Chávez and his Socialist Party. He and his family are waiting to be relocated to a new home, but Simon is thankful to the government for the opportunity to live in the tower. (Photo: Ramón Iriarte)

A 51-year-old Colombian soccer coach who immigrated to Venezuela over two decades ago, Hipólito built his home from scratch with his own hands and the help of a couple of friends of the family. He is effusively gracious from the first moment, perhaps because someone already tipped him off to the ‘Colombian reporter’ roaming the extensive corridors of the building. He is watching a football game on his huge flat-screen TV, and his wife is baking a cake for a children’s party that is taking place later that night on the 12th storey. She bakes and sells cakes for birthdays and anniversaries in the community, making a little money on the side to contribute to the household.

According to the capitalist point of view, housing is a commodity to be bought and sold like any other. According to the socialist principles espoused by Hugo Chávez, it is a fundamental right of every citizen, and the Torre de David is one of the greatest symbols of the defeat of capitalism.

Originally built as the Centro Financiero Confinanzas, this unfinished 45-storey office building stands in Caracas, the capital of Venezuela. This centrally located tower is now known as the Torre de David, after David Brillembourg, the original developer and main investor. Construction of the tower began in 1990, but three years later Brillembourg passed away, and the construction of the building was halted in 1994 due to the Venezuelan banking crisis. (Photo: Ramón Iriarte)

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The heat from the oven adds to the already oppressive heat of the Caracas afternoon. Outside it’s 40°C (104°F), but inside, the floor-to-ceiling glass walls of the tower create an oppressive greenhouse effect, a relentless reminder that the building’s ventilation system was never completed. Still, Hipólito is clearly very proud of the apartment that now stands where once there was nothing but a flat space full of rubble. He is very grateful, mentioning repeatedly that he is lucky that the people in charge of the building have given him the opportunity to have a decent place to live with his family.

This ‘decent place to live’ was originally supposed to be Venezuela’s biggest financial centre, the project of a group of wealthy financiers led by David Brillembourg. It would have housed the headquarters of Banco Metropolitano and Grupo Financiero Confinanzas, as well as foreign companies attracted to Venezuela by a series of neo-liberal economic reforms popularly known as ‘the package’. A condition of the disbursement of a new US$4.5 billion (€3.5 billion) loan by the International Monetary Fund, the package privatised state companies, dropped interest rates and liberalised oil prices, aggravating an economic situation already troubled by plunging international oil prices.

Shortly after Brillembourg’s death in 1993 and in the midst of the financial crash that affected many Latin-American economies in the early nineties, his development and construction company went bankrupt and was expropriated by the government. Construction stopped abruptly, and the unfinished 45-storey tower was abandoned for the following 15 years. As the government tried unsuccessfully to find private investors to complete the project, drug and housing mafias took control of the space, and vandalism, looting and crime reigned within and around it. The Torre de David or Tower of David, nicknamed after its deceased developer, became part of Caracas’ urban landscape, generating endless myths, tales, and anecdotes that thrived on the everyday coffee-table conversations of the locals.

On January 8th, 2011, Hugo Chávez gave a speech in Caracas, in which he expropriated seven properties belonging to Polar Industries and authorised their occupation, calling the Occupation Movement an example of self-management, a weapon in the war against the paradox of ‘people without houses and houses without people’.

Each of the inhabited floors has coordinators and maintenance workers like Cheo, who oversees the plumbing system. (Photo: Ramón Iriarte)

Because it has no functional elevators, the building is occupied only up to the 28th floor. While the occupied areas are in a state of constant modification, the upper part of the building looks just the way it was left in 1994. The stairs, which have been equipped with only minimal improvised safety measures, are the only way to get up and down. Those with vehicles use the ten-storey parking structure to get closer to their flats. For a small fee, entrepreneurial drivers ferry people and goods ten floors up or down. (Photo: Ramón Iriarte)

The horror stories, many of them true, abounded until 2007, when a group of 200 families who were unable to find housing after losing their homes to floods decided to occupy the building. These families are now known as the pioneros (pioneers), the first of some 700 families to make their homes in the first 28 storeys of the tower. Inspired by the socialist revolutionary ideology of Hugo Chávez (president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013), they and others like them undertook projects that appropriated abandoned private property and redistributed it among working-class families who needed a place to live. Today the interior of the Torre de David looks nothing like an office building, but more like a huge apartment complex, albeit one in which each unit is different from the others: though they all start as an equal, empty portion of the unfinished building, each one, like Hipólito’s, is finished by its occupants according to their needs, resources and ingenuity. They range from the basic to the more luxurious, from naked brick walls to fancier tile floors.

As different as the apartments may be, each resident has the same community duties and responsibilities, which are specified by a list of actively enforced rules of coexistence. According to Daisy Monsalve, a young assistant nurse at the delivery room of the Caracas University Hospital, and one of the first residents of the Torre de David, each floor nominates delegates who allocate rotating responsibilities to each family: each unit has the duty to clean floors and hallways once a week. Waxing the floors, painting the walls, and other general maintenance tasks are communal duties carried out when the delegates call for it.

Daisy thinks the bad image that surrounds the Torre de David in the eyes of many locals, not to mention the international press, precedes the occupation: ‘This has always been a bad neighbourhood,’ she says, ‘and since the occupation, everybody blames everything bad that happens around here on Torre residents. They say we’re thugs, robbers, scum… but we’re honest, hard-working people, and this has always been a bad area of Caracas.’ She has been living for five years now in the apartment she built with her ex-husband, working late shifts at the hospital by night and working on her home by day, and she has never had a problem even though she often comes in and out late at night. Like Hipólito, she is very grateful to have a roof over her head, and sees the tower as her permanent home. The prime downtown location and good community relations make her hope she will never have to leave. ‘When I got here, everything was destroyed, the roof, the walls, the stairs. It was full of rubble and trash, and we cleaned the entire building, which was a great sacrifice. That is why I feel so empowered over this space, because of everything we did to recover it.’

On the day that Nicolas Alvarez and Paola Medina moved into the Torre de David it took seven trips to carry their belongings up the 27 storeys to their new home. As Nicolas says, ‘Sometimes you walk up, and right when you open the door of the apartment, you realise you needed to buy something, like soap or toothpaste… man! It’s hard to get used to, but we are getting extremely fit!’

While residents pay no rent, they do pay a monthly fee of 150 Bolívares fuertes (€18.60/US$23.80) for water, electricity, security and cleaning of public spaces. Additionally, because of the instability of Venezuelan currency, many families invest in home improvements or even rental properties. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

There are 750 families living in the building, each in a residence that differs in size and form according to the skills, abilities and tastes of its inhabitants. Apartments from the 7th to the 16th storey tend to be well developed, as they were originally intended to serve as hotel rooms. By supplementing their incomes with ingenuity, however, residents manage to create spaces that are not only liveable, but personal as well. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

Conditions have improved dramatically since those early days. The inhabitants have managed to build a plumbing system that efficiently pumps water for several hours a day to the 20 to 30 families that live on each of the first 28 storeys. Occupants also filed and won a case to have the city’s electricity company install a proper electric grid throughout the building after looters stole most of what little remained from the original construction. Many squatters—like Hipólito, who rarely misses a Copa del Rey, Calcio, or Premier League game—subscribe to a cable service or use makeshift pirate antennas to get television and Internet connections in their apartments. A profusion of corners, rooms and improvised units lodge all types of commerce and services from regular bodegas to a tattoo parlour located on the 20th storey.

However, not all the news for tower residents is good. Rumours of imminent evictions constantly come and go, and many detractors of the occupation movement (even within the government of Nicolas Maduro, former vice president to Chávez) are permanently lobbying, not without valid arguments, against the use of this space for urban housing. Gustavo Izaguirre, architect and dean of the Urbanism and Architecture Department of the Central University of Venezuela, is one of those detractors. He claims that Venezuela’s strategies to combat the housing deficit are misguided, that they are pushing people to take over what he calls ‘unsuitable living spaces’ such as the Torre de David.

Movimiento de Pobladores, a squatters’ group, estimates that it provides political and technical assistance to about 2,500 families living in more than 75 of the 400 squats in Caracas alone.

The atrium was originally designed as the main entrance to the building complex. Since then it has been repurposed as a space for community meetings, sports, and increasingly, also for building new apartments in the available space, which is only a few storeys above street level. (Photo: Ramón Iriarte)

Indeed, few would consider a daily 28-storey climb, some of that up stairways without handrails, already the site of more than one fatal fall, to be a feature of a suitable living space. A home, according to Izaguirre, is not merely a structure with a living room, a kitchen, a bathroom, and bedrooms, but a much deeper concept. It is a space envisioned and constructed for specific contexts and needs, a space thoughtfully integrated with its urban surroundings. It is a concept as attractive as it is distant from the reality of Venezuelan squats.

The complexities of the housing dynamics in Latin-American cities continue to set academic and political theories against the social and economic facts of life. And though the Venezuelan government’s housing programme has built more than a half a million residences for the homeless since the start of Chávez’s revolution, many people continue to face great difficulties in finding decent housing due to market structures resulting from decades of governmental disregard for socioeconomic inequality. Those like Izaguirre regard the squat as a hazardous, crime-ridden place, an example of ‘anti-housing’, but for Hipólito, Daisy, and hundreds of other families, this colossal vertical neighbourhood is, at least for now, their home.

The 192m (630ft) Torre de David, the third-tallest building in Venezuela, was occupied by a group of homeless squatters on September 17, 2007. The first families initially set up tents and shelters in the ground-floor lobby; weeks later, they occupied and reorganised most of the building. Nearly 3,000 people have lived in this self-governed community in the heart of the former financial district. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

Addendum:

On July 24, 2014 the Venezuelan government began the process of evacuating the Torre de David, moving residents of the squat to Ciudad Zamora, a large housing complex in the municipality of Cúa, south of Caracas. As of mid-September, 50% of the occupants had been relocated, and if ‘Operation Zamora 2014’ goes according to schedule the entire building will be vacant by the end of 2014. What will become of it in the future is as yet unknown.