From Earth To Mars

Governments have drastically reduced their space exploration programmes, delegating these efforts to private enterprise. Copenhagen Suborbitals and Mars One are only two of the companies striving to prove that they can pick up where NASA left off.

Cover photo: A landscape captured by NASA’s Mars Explo ration Rover Opportunity. This photo was colourenhanced by NASA to bring out surface details and include imaging from beyond the visible spectrum. (Image courtesy of NASA/JPL Caltech/Cornell University/Arizona State University)

Refshalevej is a jumble of rusted jetties and shipping containers on a windblown peninsula that juts out into the Baltic Sea. Hemmed in on one side by a line of wind turbines and on the other by steaming cooling towers, it surrounds a giant, battered hangar, a remnant of one of Denmark’s abandoned shipyards. Fishermen cast lines off the decaying dock gates; an abandoned toilet stall squats in a lay-by overlooking the sea. Incongruous in the loading yard, a scaffold holds a thin white missile around ten metres (33ft) tall. It looks for all the world like a cargo cult parody of Cape Canaveral.

‘The tower used to be a prop for Robin Hood,’ says Mads Wilson as he picks his way through a small warehouse filled with pieces of engine, gutted electronics and discarded rolls of wire. ‘We got it from the Danish National Theatre.’

In his day job Wilson manages the software that ‘uses people’s web data against them’ for direct marketing. In his spare time he works here on rocket electronics. Professional mechanics also give up their evenings and weekends to perfect the complex welding work on the fuel tanks. On its next test launch, the cool hand on the rocket’s ‘kill switch’ will belong to an anaesthesiologist.

This is Copenhagen Suborbitals, which since its creation in 2008 has become one of the most sophisticated amateur rocket clubs in the world, dedicated to the belief that part-timers can put a man into space and bring him back alive in a capsule that uses safety floats made out of Pilates balls inflated by Sodastream machines. The pilot will actually be just a passenger; there will be no controls. ‘We have a long line of volunteers. That’s no problem at all,’ Wilson says. ‘The guy in the rocket will know it was built by his best friends.’

The rocket itself is an amalgam of reverse engineering and declassified technology from the American and Soviet space programmes, some of it from the 1950s and 60s, some of it essentially the same propulsion mechanisms used by German rocketeers during the Second World War. The liquid helium canisters used to cool the rocket are labelled ‘balloon gas’. It’s far from pretty, but Wilson insists it will work. ‘Our goal is always to find the simplest solution. There’s nothing on the rockets themselves that you can’t buy in a hardware store. They’re all industrial components,’ Wilson says. ‘A lot of it is ordinary plumbing that you would use in your bathroom.’

In an era when a trip to the International Space Station costs only about €31.3 million (US$40 million) everybody wants to be an astronaut—and the technological and cultural landscape is ready for them to try.

(Photo: Pete Guest)

Based on Russian designs from the early days of the space race, Copenhagen Suborbitals’ lander is rudimentary, but there has been no shortage of volunteers to ride in it. (Photo: Pete Guest)

In an old shipyard on the edge of the Danish capital, Copenhagen Suborbitals prepares another rocket test on a scaf fold salvaged from a Danish National Theatre production of Robin Hood. Much of the equipment meant to take an amateur into space has been begged, borrowed and repurposed. (Photo: Pete Guest)

More than 1,000 donors contribute the 100,000 Danish krone (€13,430 or US$17,130) per month it takes to keep the rocket workshop running. The rocket on the test stand represents an investment of around 200,000 krone (€26,850 or US$34,270). ‘We want to prove that we can do this just by being us. Just because we want to,’ Wilson says. ‘Of course, it would go a lot faster with more money, but it’s fun to make do with what we have.’

What they have includes computational power that was unimaginable at the beginning of the space era. The very existence of these privately backed space exploration projects is made possible by processors and components that are becoming steadily faster, smaller and more accessible. Copenhagen Suborbitals’ avionics will include accelerometers based on those found in most smartphones. The market leader in cheap satellite technology, Surrey Satellites, located in a sleepy research park in southern England, has also used commercially available mobile phone parts to keep its costs down.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The technology alone, however, doesn’t account for the sudden proliferation of privately funded space projects. Nor would the sudden availability of US government money following the privatisation of NASA’s procurement, if not for the resurgence in the romantic ideal of the inventor-industrialist. A new generation of makers is replacing the passive consumers of the Baby Boomer and Generation X eras. Kickstarter campaigns have funded everything from hi-fi hardware to genetically modified glowing plants. If you can dream it, the new cultural orthodoxy says, the technology will not get in the way.

The mad junkyard in a Copenhagen dock may represent a milestone in the democratisation of space travel, but if there is an archetype of this generation’s approach, it is Bas Lansdorp’s Mars One. In 2011 Lansdorp, a Dutch engineer and entrepreneur, sold the wind power company he had founded just three years previously, and declared that he would send a manned mission to Mars by 2023. Mars One, the initiative he launched at press conferences in Shanghai and New York, took a distinctly modern approach to the new space race, beginning without proprietary technology and with a mere fraction of the financial resources of the Silicon Valley rocketeers.

The announcement was, quite simply, that Mars One was sending its own astronauts, and that anybody could apply. The funding for the project would come, the company said, from the sales of global television rights. A reality TV show concocted around the lives of the wannabe astronauts as they competed to join a crew to Mars would be an unprecedented media event. The lives of the colonists and the aspirations of a generation to join them in space could be packaged for advertisers. More than 200,000 people applied, posting online videos that ranged from the heartfelt to the ridiculous. Just over 1,000 made the first cut.

It is a project so seemingly absurd that even some of its supporters and applicants admitted that at the beginning they worried that it was all an elaborate hoax. Regardless, it made headlines around the world. The practicalities barely seemed to matter, although an increasingly impressive advisory board featuring experts from mainstream aerospace research has lent credibility to the project.

Not everyone is on board. The General Authority of Islamic Affairs and Endowment, a religious rule-making body of the United Arab Emirates, has declared that the one-way trip is so dangerous that it is equivalent to suicide. They issued a fatwa declaring it to be un-Islamic and urged Muslims not to sign up.

In the past decade, private space programmes have become the must-have accessory of the post-dotcom Silicon Valley set. Billionaire PayPal founder Elon Musk has SpaceX, while Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, is the keystone investor in Blue Origin, which hopes to compete for the same business. Google co-founder Sergey Brin was among the early investors in Space Adventures, a space tourism venture.

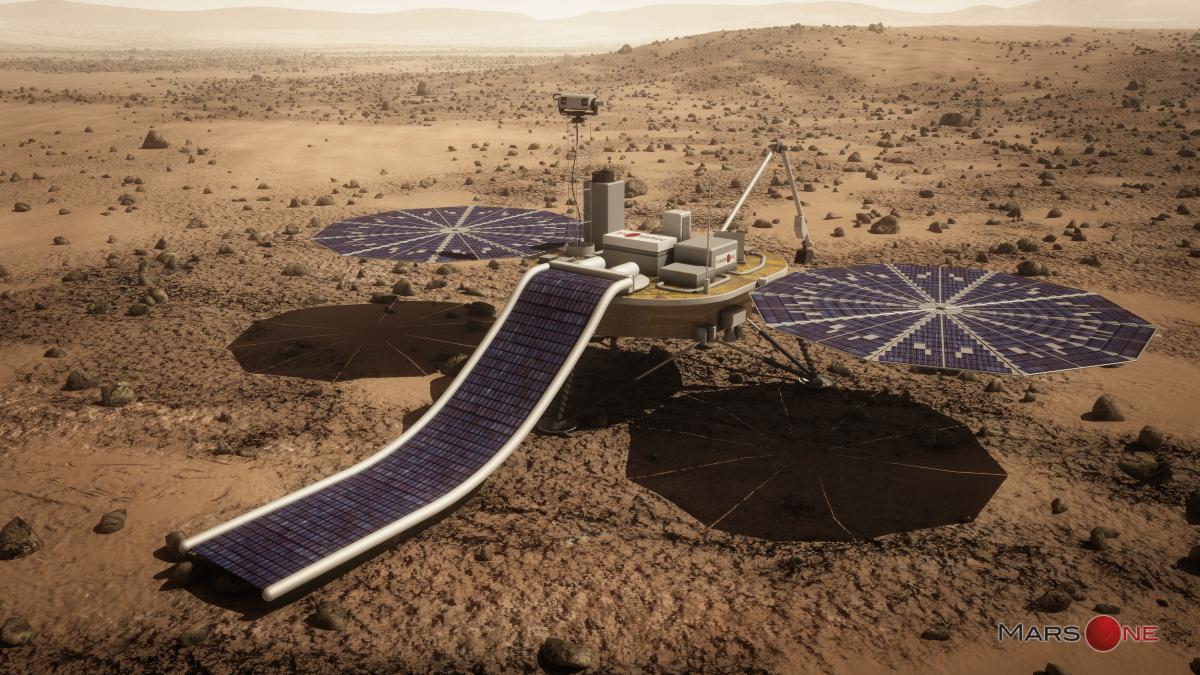

Mars One plans to land all components for its permanent human settlement by 2021. The hardware includes two living units, two lifesupport units to generate energy, water and breathable air from Martian resources, a cargo supply unit and two rovers. (Artist’s rendering courtesy of Bryan Versteeg/ Mars One.)

Some from the scientific mainstream, however, are supportive. Professor Morten Bo Madsen, who has worked extensively with NASA and the European Space Agency on Mars missions since the 1997 Pathfinder probe, says the ‘pay-per-view’ mission is ambitious, but ultimately laudable. ‘It’s a couple of guys who lost patience with the public way of doing stuff. They wanted to kick some speed into going to Mars,’ he says.

Bo Madsen’s office at the Niels Bohr Institute, in a suburb on the opposite edge of Copenhagen, is a gallery of rover diagrams, Mars globes and newspaper clippings from a decade’s worth of projects. His team specialises in designing magnetic experiments for Mars missions, and over the past two decades he has come to appreciate how little room there is for error in space, particularly in Mars exploration. The past few generations of Mars programmes have made huge discoveries about the planet’s geology and discovered water, but hundreds of millions of dollars have been lost in missions that have failed en route, in orbit, or once on the planet. The expected lifespan of a Mars rover, Bo Madsen says, is 90 days.

Bo Madsen lists the tiny errors—software malfunctions, badly adjusted mirrors, memory card failures—that have derailed missions, punctuating each example with a wry laugh. Delays are almost inevitable. Curiosity landed on Mars in 2012, two years behind schedule. ESA’s flagship Martian probe, ExoMars, was set for launch in 2009, but won’t be ready until 2018 at the earliest. Furthermore, there are narrow windows in which missions can be launched, windows during which Earth and Mars are closest to each other. They occur only once every 26 months; miss one, and another will not come around for more than two years.

However, Bo Madsen notes, Mars exploration to date has also been a story of making it up as you go along. Tools fitted to the rovers—spectrometers, cameras, drills and scrapers—have often been repurposed remotely. The operations of multimillion-dollar space programmes are at times not too far away from the improvisation of Copenhagen Suborbitals.

Mars One has moved forward since the fanfare of its launch. It has signed memoranda of understanding with major aerospace companies, including Lockheed Martin and Paragon Space Development Corp. It issues a steady stream of press releases announcing new advisors and partners, and in June it signed up with Darlow Smithson Productions, a subsidiary of Endemol, the Dutch production company behind the Big Brother brand.

In March 2014, Mars One announced that the man who would lead its habitat programme, taking responsibility for the survival and wellbeing of the amateur astronauts, would be Kristian Von Bengtson, one of Copenhagen Suborbitals’ cofounders, who quit in February after falling out with his fellow engineer Peter Madsen. Madsen too has since left to pursue his own projects from a small corrugated iron hangar immediately opposite Copenhagen Suborbitals’ facility.

Von Bengtson met Lansdorp when both were consultants for the European Space Agency in 2005. ‘When I was looking for something new and interesting in space and capsules it was natural for me to call Bas. This is what I do, work space missions with an edge and a vision. Mars One has all that,’ Von Bengtson says.

There are now more spacecraft in museums than in orbit. NASA funding has been sharply reduced, and international space exploration is being affected by the strained relations between superpowers, but private investors are now making significant contributions to space science missions and eventual space colonisation.

Mars One is working with Lockheed Martin to develop a robotic lander spacecraft. The lander is based on the Phoenix spacecraft developed for NASA’s successful 2007 mission. (Artist’s rendering courtesy of Bryan Versteeg/Mars One.)

He is quick to point out that Mars One’s safety features will be considerably more sophisticated than Pilates balls and Sodastream machines. ‘The only similarities […] between the two projects are the dedication and the belief that private [enterprise] will lead us all into a new era of spaceflight for everyone,’ he says. ‘Copenhagen Suborbitals was all about building your access to space, building your own rocket with your own hands.’ But Mars, Von Bengtson says, is no place for amateur designers.

Mars enthusiasts have set up a number of ‘analogues’, environments meant to simulate conditions on the Red Planet. The Mars Society, Robert Zubrin’s advocacy organisation, has constructed one in the desert in Utah. A second, planned for Iceland’s Arctic north, was damaged in transit and never deployed.

None comes close to providing the true experience. Not only does Mars feature brutal sub-zero temperatures all year round and a permanent desert environment without liquid water, it is also racked by dust storms and volcanic activity. Worse still, without Earth’s protective atmosphere, radiation levels are hazardously high. A Martian habitat would need to be weather-sealed, radiation-shielded and totally airtight, while also being portable enough to ship on the eight-month voyage. The Curiosity mission delivered a payload of 900 kg (2,000 lb). Mars One will need to ship several times that.

Von Bengtson believes that the technology to keep the astronauts alive already exists. Radiation shielding could be achieved by burying the habitat under dust or ice, he explains. ‘Obviously there are a lot of technical requirements related to having an outpost on Mars, such as pressurisation, air-lock design, dust prevention and life support systems,’ he says. ‘But Mars One is based on existing technology, so no Nobel prizes are needed for us to do our work.’

Technology is only half of the battle. The prospective colonists are signing up for a lifetime on Mars, and their habitat has to be more than simply functional. ‘The biggest challenge is creating an outpost where people can live their entire lives. The outpost has to support every aspect of a human life and group living as well. The interior design has to be very flexible and will be evaluated while training is taking place to optimise the design and performance of the architecture,’ Von Bengtson says. ‘It’s relatively “easy” to get technology working, but humans are much more complex.’

In interviews, most applicants to Mars One demonstrate a startlingly blasé approach to their impending deaths on a distant planet, but a straw poll shows that the most common worry is simple boredom: what they are going to do all day.

3D rendering of the Mars One 2025 farm. (Artist’s rendering courtesy of Bryan Versteeg/ Mars One.)

Among them, though, there is one applicant who is uniquely qualified to speak about the total isolation and constant danger of extreme and remote living conditions: Dr Robert Schwartz, a physicist who has spent ten winters in the Antarctic, working for eight months at a time in a habitat cut off from the outside world. ‘It’s not such a bad gig if you think about it,’ Schwartz says on a crackling satellite phone line from Antarctica. ‘I’d rather do that than writing papers or anything like that, like most of my colleagues have to do.’

Working in an Antarctic winter without so much as a supply plane and with only intermittent satellite communications with home is a challenge requiring constant improvisation and innovation. The infrastructure on the base is being rebuilt, but the old facilities have been continuously jerry-rigged to keep them functioning and liveable. Newer habitats, while they might be more efficient, are often designed without direct experience of the extreme conditions that they will face, according to Schwartz. ‘When I got down there the first time the station was 22 years old. Nobody said anything if you remodelled your room,’ he says. ‘We got the buildings we wanted because we did it ourselves… you know out of experience what you want.’

Schwartz signed up to Mars One after failing to make the final cut to be an astronaut. He was in the last 2% of applicants to ESA, and missed out at the last hurdle. His job has taught him enough about isolation to harden him to the harsh realities of a one-way trip to Mars. ‘When I come to the Antarctic I know I will return again, back to the green world. We definitely give up things that seemed normal to us,’ he says. ‘You return to New Zealand [the staging point for the Antarctic station], and you come out and you smell grass again. After your first year you reach down and touch the grass. There are small things that you absolutely took for granted and you appreciate more again. There are things you miss, but every year you adapt more to it. You think you are going to miss things… but you realise that though they would be nice to have, you can live without them.’

He is fatalistic about his chances. Given the radiation, cancer is a near certainty, he says. The mission is hugely complex, fraught with risk and ending in a lonely death. ‘Mars would be for humankind, and for me personally, an absolute adventure. In 15 to 20 years, I would be of an age where I could live a few more years on Mars and maybe go out with a bang, rather than end up in a retirement home with Alzheimer’s,’ he says. ‘Of course, we have much more stuff [in Antarctica] than we would have on Mars. You would have to improvise more.’ He pauses. ‘I know what I’m getting into.’