Constructing the World’s Biggest (Disassemblable) City

The 2013 Kumbh Mela in Allahabad was the largest peaceful gathering in human history. An entire city was built for the occasion, but unlike the facilities built for the Olympic Games or other international events, this city was designed to be erected, inhabited and dismantled all in the space of a mere five months.

Cover photo: The construction of the temporary megacity could start only after the end of the monsoon, when the river had receded to its normal course. Tractors were used to form mud and sand into flat, level street foundations, which were then covered with a total of 75,000 1 m × 5 m (3.3 ft × 16.4 ft) steel plates to create 156 km (97 mi) of new roads. (Photo by Felipe Vera)

Every four years millions of Hindus celebrate the Kumbh Mela, the Festival of the Urn. The location rotates among Nashik, Ujjain, Haridwar and Allahabad (Pragaya), four riverside cities where, according to an ancient legend recorded in the Bhagavata Purana, drops of amrit, the sacred nectar of immortality, fell to earth during a supernatural 12-year battle between the Devas and Asuras. When the sun, moon and Jupiter recreate the celestial configuration that witnessed this event, pilgrims gather to bathe in the rivers and gain their spiritual benefits. The four locations are not equally significant. The Kumbh Mela is most sacred and most visited when it is held in Allahabad, as it was in 2013 when more than 100 million people from all walks of life came to bathe in the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers during the 55 days (January 14th to March 10th) of the festival.

This would be a marvel of civic planning and logistics even if the festival were held in Allahabad itself, but it is not. Instead, in just eight weeks, a nagri (temporary city) springs up on the riverbanks, on an otherwise uninhabited floodplain that was under water only a month before the start of construction. On the most important days of the 2013 festival, attendance reached an estimated 30 million people (or roughly the combined populations of Belgium and the Netherlands), so this temporary city had to provide not only lodging and provisions, but an entire infrastructure complete with roads, bridges, sanitation, power grid, hospitals, seven train stations and a police force of over 12,000. In the three weeks after the festival ended, the entire city was disassembled and the plain returned to the rivers, which would flood it again a month later. How does an entire megacity rise, flourish, fade and disappear in just five months?

The site of the Kumbh Mela is a temporary city whose population fluctuates between 3 million inhabitants on regular days and 30 million inhabitants on the festival’s most holy days. Shanghai, the world’s largest permanent city, has a population of about 24 million.

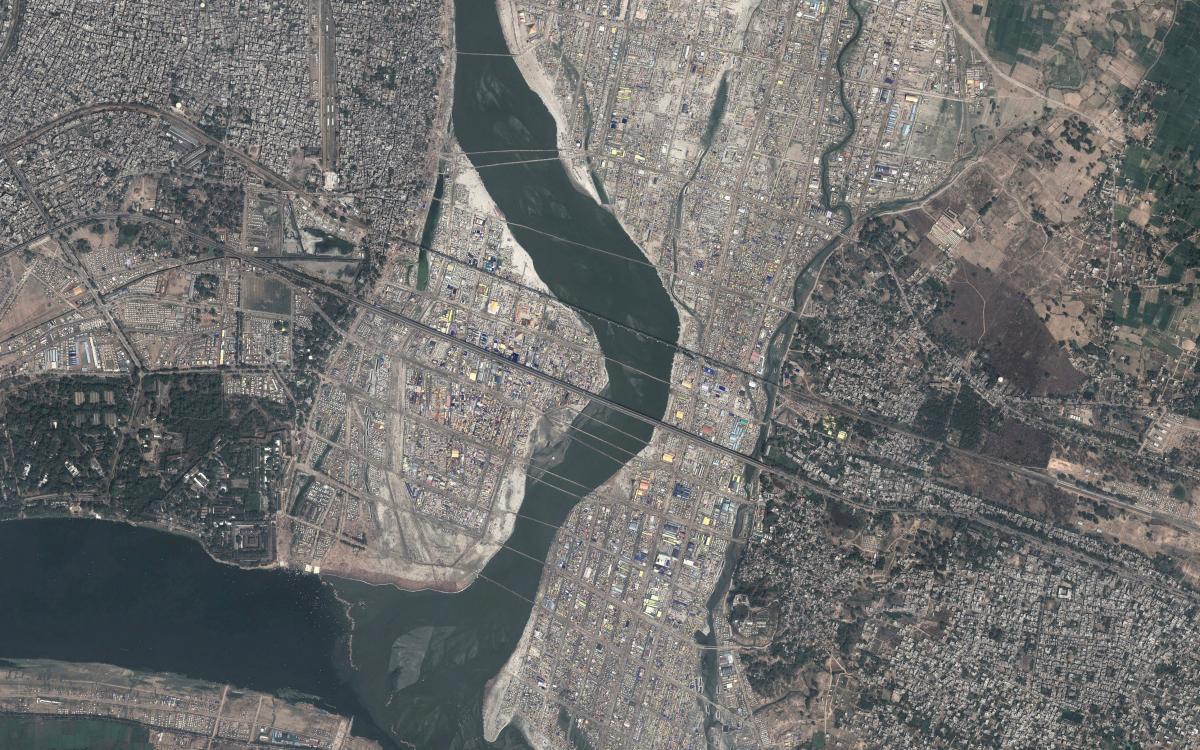

The Kumbh Mela is a Hindu religious festival that rotates among four sites located on four sacred rivers, Haridwar on the Ganges, Ujjain on the Shipra, Nashik on the Godawari and Allahabad at the confluence of the Ganges and the Yamuna. This satellite photo from October 13, 2012 shows the vacant floodplain. A month prior this area was under water; three months later it would welcome millions of pilgrims from all over the world to the largest temporary city on earth. (Photo courtesy of Google and DigitalGlobe.)

The construction of the temporary city started in Novem ber 2012, when the ground was dry enough to be levelled so that roads could be built. The festival began on January 14, 2013, giving organisers just eight weeks to prepare the site. Maha Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, is the largest of the rotating festivals, happening only once every 144 years under a par ticular astronomical configuration. This satellite photo is from February 8, 2013, just two days before the most auspicious bathing day of the Maha Kumbh Mela. (Photo courtesy of Google and DigitalGlobe.)

The climatic, logistical and time constraints of the project make meticulous planning a matter of success or failure. Planning for the 2013 festival started in February 2012 and was a cooperative effort between the permanent city of Allahabad, the temporary city of Kumbh Mela, and the state of Uttar Pradesh. By early March of 2012, the construction equipment was being inspected and repaired, much of it having circulated around the subcontinent, serving other projects and festivals. Supplies and materials were being gathered, contractors and subcontractors hired; everything had to be ready to go once the monsoon season ended and the riverbanks emerged from the water in late October.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.When the floodwaters receded the Public Works Department of Uttar Pradesh state began construction of the pontoon bridges that spanned the rivers, and which were the most intensively used component of the city’s infrastructure. The 2013 Kumbh Mela required 18 bridges over the Ganges, gigantic constructions resting on a total of 4,202 pipas, floating steel structures 9.75m (32ft) long and 2.5m (8ft) wide, each weighing nearly five and a half tonnes. Bamboo tripods sunk into the riverbed anchored the bridges, and the pipas, lowered into the water by a specially modified flatbed truck, were spaced about 5m (16.4ft) apart from each other. They were connected by steel cables above the waterline and coir rope under water, and after they passed inspection an arrangement of beams and sleepers similar to railway tracks was bolted to them. At the height of the festival each bridge had a crew of 30–35 carrying out regular inspections and repairs to ensure the safety of the multitudes crossing the rivers to get to and from the residential areas.

Estimates of the number of people bathing on February 10, 2013 vary, but the most common estimate is about 30 million, making this event the largest peaceful human gathering on record. In total, an estimated 100 million visitors participated in the Kumbh Mela over its 55 days. (Photo: Jiva Gupta)

The bridges had to be in place by November when the ground was dry enough to be levelled and stabilised, so that the roads that served the nagri could be built, including roads connecting it to Allahabad on the west and Varanasi on the east, as well as roads that defined the grid of the festival city itself. The ‘permanent’ main streets of the city were laid out according to tradition, their names and alignments the same as in every iteration of the festival. They were built of bitumen in stabilised ground outside the flooding areas, approximately 0.6m (2ft) higher than ground level at the centre and gently graded on both sides to ensure drainage. (Although historically these roads had been rolled using manual labour, for the 2013 Kumbh Mela, they were built using tractors for the first time; still, the estimated 156km (97mi) of steel plates laid down them to support the wheels of cars and other vehicles were carried and positioned by hand.) As the main roads took shape, the smaller ‘temporary’ paths that connected them were made of poured sand, a natural material providing good drainage and that would return to the riverbed during the flooding of the monsoon season. This network of roads established the division of the city into sectors (the 2013 festival had 14, three more than the previous one), and the division of the sectors into a regular grid of smaller residential quarters which were assigned to various religious groups and tourist agencies. It also organised infrastruRahul Mehrotractural elements such as water, electricity and sewerage.

There are about eight weeks between the day that the floodplains are dry enough to begin constructions and the day that the first inhabitants arrive. Between the day that the last inhabitants leave and the day that the floodwaters return there are about seven weeks.

During its 2,000 years of existence the Kumbh Mela has grown to tremendous proportions, and the supporting infrastructure has had to keep pace. For the 2013 festival a crew of 1,700 workers constructed 18 pontoon bridges to accommodate the vast numbers of pedestrians needing to cross the river. The largest bridge covered a 725 m (0.45 mi) span. To optimise traffic flow during peak periods, the bridges become oneway according to demand. (Photo: R.M. Nunes)

By December the city grid was complete and structures began to rise. More ‘permanent’ facilities such as hospitals were built of plywood, while cotton tents served as residences and venues for spiritual meetings. There was no master architect for the nagri, and in fact the festival administration employed no architects at all, so each group was responsible for the construction of the section of the grid that it would inhabit and brought in its own contractors and construction teams. The festival site became a collage of cotton, bamboo, tin, plywood and plastic, materials typical of Indian slums, here converging in a constantly changing texture of materials and styles. By January, a fully functional city capable of supporting millions of residents stood where two months earlier there had been only a muddy plain, and throngs of holy men, teachers, students, tourists and service personnel brought the city to bustling life.

Although many temporary structures built on a grid are marked by a dehumanising conformity, visitors to a Kumbh Mela traverse a lively medley of individual expressions as they pass through the city. Unlike many housing developments, refugee camps or cubicle offices, the festival site consists of regularly shaped but autonomously conceived areas in which each community is authorised to organise its space in the way that most accurately expresses its own identity. Some are more spontaneous, others more systematic. Although the procedures that regulate the allocation and organisation of the spaces are well established, they have never been explicitly codified in any document; rather the traditions are passed on from participant to participant over the cycles of the festival and modified as needed.

(Photo: Rahul Mehrotra)

About 700,000 tents were erected to house the visitors; they ranged from the simplest makeshift constructs to luxurious heated tents with room service, serving occupants from all corners of the world and all walks of life. (Photo: Vadim Kulikov)

While the Kumbh Mela is essentially a religious devotional festival, it requires massive secular machinery to ensure the coexistence of visitors. Besides 125 food stores, there are several food markets, and many companies use the festival to reach out to rural consumers. (Photo: Vineet Diwadkar)

The sector that houses the akharas, or sects, is a good example. In accordance with tradition, the area for each sect is organised around an identifying flag, which stands in the centre of its space and is clearly visible from the street. Areas for the tents of the gurus and their followers are distributed around it, with the most prominent gurus located along the path from the main entrance to the flag. The importance of each guru is connected with the number of devotees he attracts, which is manifested in the organisation of space at the Kumbh Mela: locations with prime exposure are given to more prominent gurus, allowing them to gather more potential followers, and when one teacher’s followers become too numerous for the allotted space, a new akhara is created with its own space and flag. The akharas themselves are also arranged within the sector according to their prominence, with Juna Akhara, the biggest and oldest of the sects, occupying a privileged spot.

As enormous and complex an organism as the festival site is, it may seem impossibly low-tech in an age when the word ‘infrastructure’ typically denotes a city’s most fixed and durable elements. But it is precisely this approach that enables the nagri to adapt to the needs of its inhabitants over each of its brief incarnations. The modularity of steel plates that can be carried by four men is what allows them to be deployed anywhere a road is required. The simplicity of hand-stitched cotton tents stretched over lightweight bamboo frames enables them to be concatenated into the skeleton of a megacity, whatever shape it may need to take, and in whatever colours and patterns may be desired. Heavy machinery and advanced technology are, for the most part, not required, nor are highly trained specialists. It is a strategy that serves not only the Kumbh Mela, but also the whole regional economy, because after the festival ends, the city is dismantled and its components are quickly and effectively recycled or repurposed, with metal and plastic items finding their way either to storage or to other festivals and construction projects. Biodegradable materials such as thatch and bamboo are left to reintegrate with the site, which, nurtured by the floodwaters, serves as valuable agricultural land for the 11 monsoon cycles between festivals. There is much here that could be applied to other non-permanent settlements such as refugee camps or disaster relief efforts, as well as to future urban design and redesign projects.

Wherever armed conflicts or natural disasters force the relocation of masses of people, there are opportunities to apply the modular low-tech solutions that provide millions of pilgrims with housing, utilities, transportation and public services during the Kumbh Mela.

The megacity that sprang up next to Allahabad for the Kumbh Mela was nearly 30 times larger by population than the host city, larger than New York, London and Paris combined. To accommodate the millions of pilgrims, more than 35,000 toilets were installed, 14 temporary hospitals built and 12,461 police officers deployed. The vibrant metropolis was com pletely dismantled 55 days later. (Photo: Jiva Gupta )

Still, perhaps the most valuable lesson to be learned from all this is a sense of humility. Festival participants would say that the Kumbh Mela is ‘about renunciation’, an idea that is embodied in its physical manifestation: no building, no road, no garden is permanent, no matter how carefully planned, arduously constructed or lovingly tended, and the act of creation must necessarily be followed, even complemented, by the act of letting go. The ground claimed from the river is only on loan: from mud it was created and to mud it must return.