Branding the World’s Newest Country

South Sudan’s Independence Day was set for only six months after the referendum that established the new country’s independence from Sudan. In that short time state symbols had to be proposed, refined, adopted and promulgated to a country still torn by internal conflict.

Cover photo: Presidents Bashir (Sudan) and Salva Kiir (South Sudan) watch the parade at the independence ceremony of the Republic of South Sudan. (Photo courtesy of United Nations)

Sometimes the walls of a house are erected before the ground within is fully levelled. In many ways South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, is like a rough foundation dig surrounded by gilded cement walls. The symbols and semblance of nationhood exist: a flag, coat of arms, banknotes, a cultural complex, even a national beer. The visual marks of its national identity in place, it presents itself as a complete, if fledgling, country, a legitimate start-up nation able to fly its unique flag among the 192 others in the United Nations General Assembly. But as the ongoing civil war attests, the state of South Sudan is still disputed within its borders, divided along political and tribal lines into hostile factions. As a nation and as a concept, its citadel is erected on marshlands.

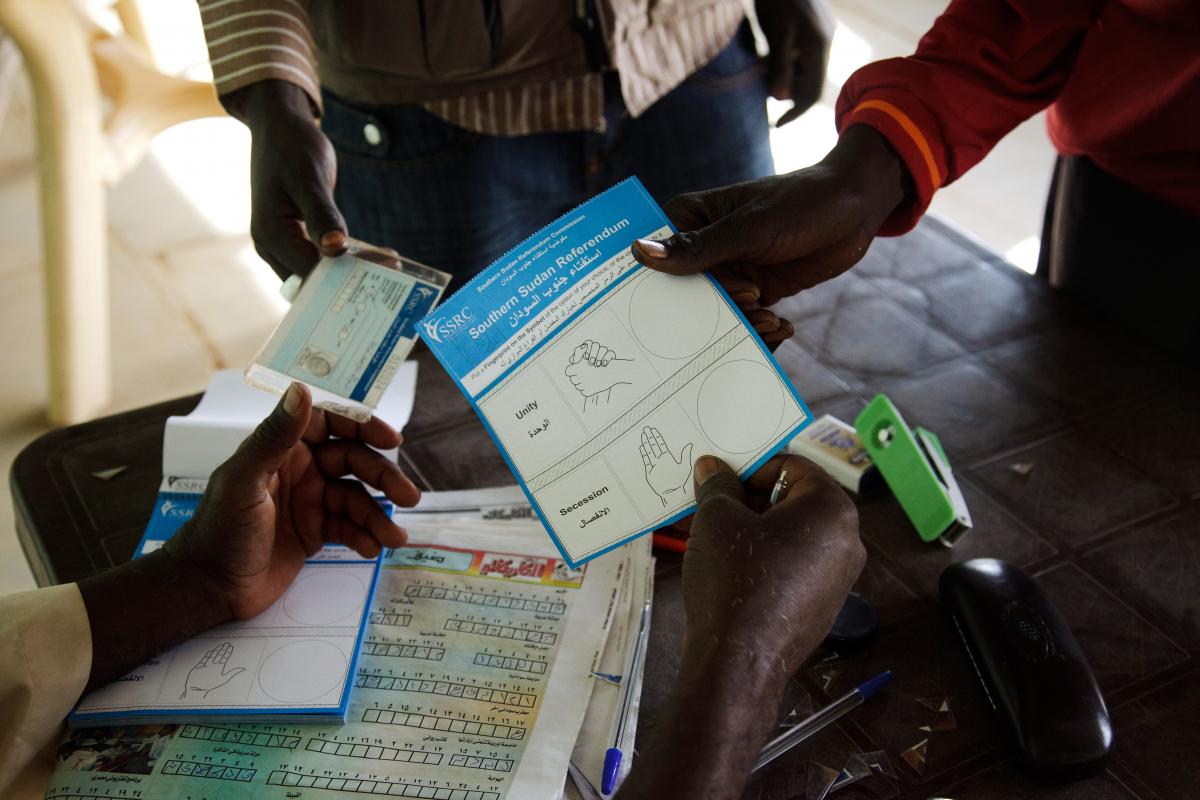

The referendum that set South Sudan on the road to statehood was itself a demonstration of the importance—and the challenge—of choosing meaningful symbols. To ensure the widest possible participation in a region with a 27% literacy rate (according to UNESCO, the lowest in the world), the Southern Sudan Referendum Commission decided to use pictures to represent votes for separation from or continued unity with Sudan. But selecting symbols that would be readily understood across Southern Sudan’s more than 60 diverse tribal groups proved difficult, and the choice of two clasped hands to signify unity and an open palm to signify independence was the subject of much controversy. Still, the referendum resulted in a 98.83% affirmative vote for independence from Sudan, ending decades of civil war against the north. With the official declaration of independence set for July 9th, its officials had less than six months to gestate a nation and its symbols.

South Sudanese women waiting to cast their vote at the Giyada polling center, in Nyala in the South Sudanese referendum on 9 January 2011. Around four million South Sudanese voted to decide whether the region should remain united with the north or secede to establish an independent state. (Photo: Albert Gonzalez Farran / UNAMID)

An officer checks a voter’s identity at the referendum on South Sudan’s independence at El Fasher polling centre, North Darfur. Ravaged by over 20 years of civil war, South Sudan was left impoverished. The literacy rate for people aged 15 and older is only 27%, the lowest rate of all countries that gather such data. (Photo: Olivier Chassot, United Nations)

The flag at least was easy. The six-colour design is a carryover from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). The red, green and black stripes signify their pan-Arabic roots, while the blue pennant symbolises the waters of the Nile, and the yellow star a guiding light. Though proposals for new flag designs were considered, keeping the SPLM flag was a sentimental and strategic decision. After all, it was under that banner that the people of Southern Sudan had gathered and fought during the two civil wars. Designing the coat of arms, South Sudan’s single new post-referendum marker of national identity, proved to be more challenging.

The tradition of using heraldic coats of arms dates back to 13th-century England, and their primary purpose was to identify combatants whose identities were concealed behind metal helmets. Then, it was imperative that graphic elements be distinct enough to be read clearly in the fury of battle, but during an age when hand-to-hand combat is no longer the primary means of engagement, the need for uniqueness is less urgent. These days the coat of arms serves as a validating seal for a state’s passports and other official documents, conferring official status and legitimacy to places, papers and people. With South Sudan’s global launch set in stone, the project deadline could not be negotiated, but the seal’s graphic design had to be fully vetted.

The coat of arms of the Republic of South Sudan was adopted in July 2011. The design consists of an African fish eagle standing against a shield and a spear. According to the official description, the eagle signifies ‘vision, strength, resilience and majesty’. The eagle as a symbol of Arab nationalism is also used in the state emblems of other countries, including the Republic of Sudan, from which South Sudan separated.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The final design consists of an eagle and a shield over a spade and a spear. ‘It’s a fish eagle,’ explains Hakim, a graphic artist and project manager at Juba County Printing Press. He was a member of the technical committee handpicked by the Minister of Culture to propose, refine and finalise the state emblem.

Hakim works in a cavernous warehouse with a full suite of Heidelberg printing equipment, all of it broken, he explains, apologising for the darkness. The 40-something veteran pressman wears a simple white button-up adorned only with a commemorative pin bearing the South Sudanese coat of arms. He wears it daily, he says, touching the pin on the pocket just below his heart.

‘The fish eagle is powerful. It can pick up a small crocodile with its claws. It has great vision and can see from afar,’ Hakim says, taking it off for closer inspection. The choice of motif is intriguing: a bird of prey often mistaken for a raptor, the fish eagle is a kleptoparasite that feeds by stealing food from other birds. When probed about its symbolism, Hakim ignores the question.

Every self-respecting country has a unique name, national flag, anthem, coat of arms, banknotes, passports, letterhead and stationery. Newly formed countries have to design them.

What of the fact that the fish eagle is actually Zambia’s national bird and is also used in its seal as well as in Namibia’s? Did they consider other animals for the emblem? Other motifs? What about the bull on the billboards advertising White Bull Beer: The Taste of a New Nation? What about other motifs? After all, they were designing for the world’s newest country and they could have picked anything. ‘This was what the majority liked. Ultimately, the vice president decided. And that beer is from South Africa, not South Sudan,’ he replies.

Hakim explains that the most debated design element was not the eagle but the shield. As a nation comprised of ten states with more than 60 tribal groups, the design on the shield could not resemble any markings from any one tribe too closely. The challenge was to find a pattern that was neutral yet meaningful, an inclusive and unifying symbol for all. Huddled around a computer running CorelDraw, the nine-member committee bonded during long nights away from their families, turning around the successive versions of the design as rapidly as possible.

In every round, all 28 cabinet ministers were required to comment, essentially to function as art directors, making consensus an elusive goal. ‘Drop the wings… turn the head to the left…’. Still, after weeks of debate, the National Legislative Assembly ratified the final design in June, barely four weeks before Independence Day. There was no time to celebrate. Official documents, medals, passports, letterheads, business cards, signage and a long list of communication materials had to be prepared before the Independence Day celebration. Hakim’s co-committee member, Stanislau Tombe, a graphic designer and technical manager at the national printing office who was in charge of finalising the design for the passport, shared that in their haste to meet the deadlines, the coat of arms on the cover of the initial run of the South Sudan passport was actually the penultimate version and not the final one, but nobody was looking too closely. They were ready by the deadline, and that was good enough.

Stanislaus Tombe Felix, a graphic designer at Juba County Printing Press, finalising the new state emblem. The emblem was selected from the 26 received entries, including a submission from the artistically inclined minister of health (whose design was not selected). Chol Anei Ayii took first place and later sued the government for defaulting on the US$5,000 cash prize. (Photo: Anne Quito)

Commemorative pin bearing the South Sudanese coat of arms. According to Hakim, the central shield was the most debated design element. South Sudan is a nation comprised of ten states with more than 60 tribal groups, and so the design on the shield could not resemble any markings from any one tribe too closely. (Photo: Anne Quito)

From an outsider’s point of view, there is nothing remarkable about the design of the South Sudan coat of arms. It is formulaic, a non-design design, its eagle-shield-cartouche combination so commonplace that it looks ready-made, the graphic design equivalent of an instant meal: just add flag.

For a population so determined to separate itself from the north, South Sudan chose a design that is essentially a reinterpretation of the Sudanese coat of arms. The eagle has a softer, friendlier expression, its wings fanning around its body in a pleasing pattern, almost like something from a comic book. In contrast, Sudan’s state emblem, bearing the words ‘Victory is Ours’, is all business. It features a secretary bird with a severe expression bearing a shield from their 19th-century ruler Muhammad Ahmad. With the bird’s outstretched wings forming a forbidding X, it is a symbol not to be crossed. In comparison South Sudan appears to be the protagonist, perhaps even the young, naïve underdog that gets the audience’s sympathy.

To forge ‘a collective national identity’, the Ministry of Culture proposed the creation of the national archives, scheduled to be constructed by 2015. Funded by the Government of Norway and currently in the design stage, the South Sudan National Archive Project is to conserve and catalogue historical government records of South Sudan dating from the colonial era up to the 1980s. (Photo: Nicki Kindersley)

When asked if he likes the final design of the emblem. Hakim smiles widely, deftly slipping the pin back onto his shirt pocket. ‘I’m very proud to have been part of the process. It’s a story I can tell my grandchildren,’ he replies, welling up with emotion.

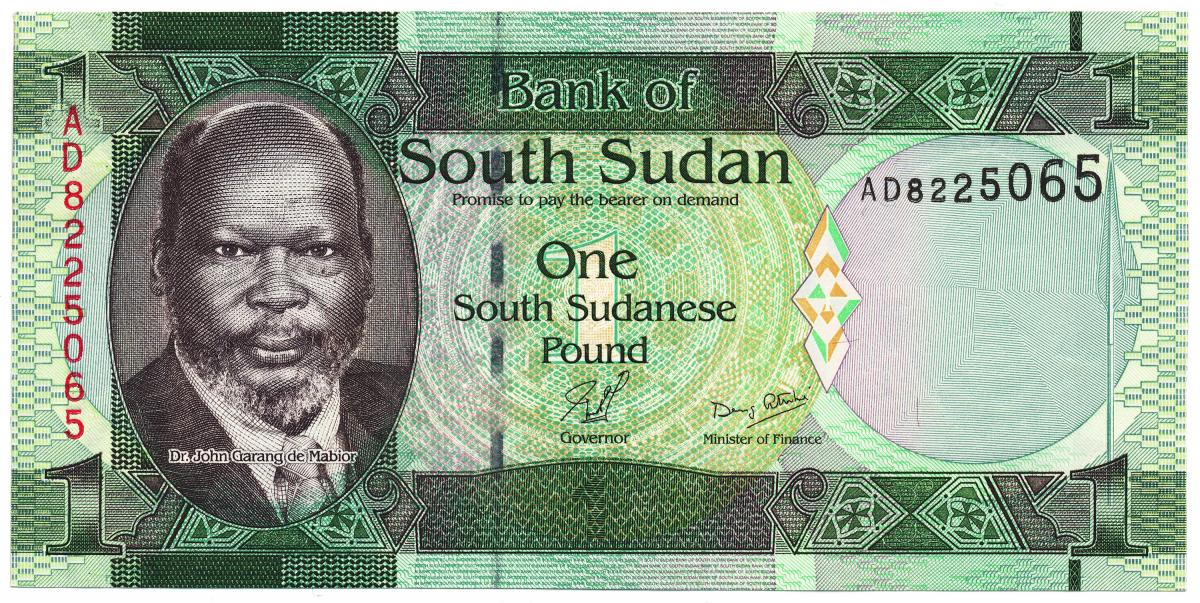

Perhaps by the time Hakim’s grandchildren are old enough to appreciate the story there will be ATMs in Juba, or at least ATMs that are easy to find, but for now, according to locals, the black market moneychangers are the quickest and easiest way to get local currency. They can be found hanging around the marketplace and prefer clean, crisp hundred-dollar notes. After haggling over the exchange rate (typically US$ 0.20 or €0.15 to the South Sudanese pound) they hand over a random assortment of dirty bills, all of which, regardless of denomination, feature the face of Dr John Garang, the enigmatic US-educated politician and former leader of the SPLA. Garang’s untimely death in a 2005 helicopter crash was mourned by the entire nation, and he was quickly raised to the status of South Sudan’s singular and uncontested national hero. The reverse sides of the banknotes feature symbols of wealth such as cattle, ostriches, lions or the Nile River, but Garang is the dominant figure in the entire series.

The Shahdad Standard is the oldest known flag in the world. The square bronze flag from Shahdad, Iran dates back to about 2400BC. In the ancient times flags were mostly used in battles to identify armies or military formations.

South Sudanese children rehearse a dance routine to be performed at half-time during South Sudan’s national football team match with Kenya as part of the Independence Day celebrations. (Photo: Paul Banks, United Nations)

Like the coat of arms, the currency had to go from design to circulation in only six months. When the first shipment of banknotes arrived, flown into the country in ‘planeloads of cash’, as their finance minister described it, they bore the signature of Elijah Malok, acting governor of South Sudan’s central bank, in spite of the fact that he had not yet been officially appointed at the time the notes went to print (and was replaced shortly thereafter). Far more seriously, the banknotes were missing dates of issue, critical for identifying defects and counterfeit bills. With much fanfare, however, the new suite of banknotes was launched and put into circulation just nine days after the Independence Day declaration, despite its flaws. The officials were so pleased with how they turned out that three months later, they printed a series of smaller-denomination bills called piasters, acting on the perceived need for low-value bills to break up the 1-pound note. The piaster design echoed the original set of notes so closely that ultimately the piasters proved too confusing to be traded, especially for a constituency where only one in three people can read. These low-value notes were printed but never put to use, their circulation limited to collectors on eBay.

This is not, however, the only currency design project to take place in the new country. When civil war erupted in the capital city in December of 2013 it set ousted vice president Riek Machar against president Salva Kiir. The following March, Machar, who had been in charge of developing South Sudan’s state symbols, issued his own banknotes to be used in rebel-occupied territories. He is also reported to be designing a new state flag and redrawing the South Sudanese map to represent new territorial divisions.

In such a state of political unrest and armed conflict, at a time when paved roads, an effective education system and safe drinking water are sorely lacking, it may seem preposterous, even irresponsible, to contemplate the construction of a national archive. But former undersecretary at the Ministry of Culture Jok Madut Jok, one of South Sudan’s most vocal cultural champions, speaks about the pragmatic imperative of building cultural institutions during a state’s nascency. In an address to UNESCO, he emphasised the urgency of forging ‘a collective national identity, so that the citizens are able to see their citizenship in the nation as more important than ethnic nationalities. […] It is important to view cultural diversity as an asset that must be put to use for building a nation.’ He argued that it ought to share priority with matters such as education, health, and governance because it dealt with the most critical agenda: forging a sense of kinship and peace within the diverse land.

The National Archives, originally set to open in 2015, was a birthday gift (or push present) from the people of Norway on the occasion of South Sudan’s independence. The building is part of a planned cultural complex in Juba that will include a museum and theatre as well as facilities for the storage and digitalisation of records dating back to the colonial era (and which were kept for years in a tent). The winning design by the Portuguese architecture firm Sitios e Formas and its local partner Beny Design is intended to reflect the African habit of gathering under the canopy of a generous leafy tree to socialise and to find respite from the heat of the day. It features a flat circular roof that shades and connects several smaller buildings.

In a revealing scene in State Builders, a documentary about the days leading up to South Sudan’s declaration of independence, Lise Grande, the UN Coordinator for South Sudan, is shown approving the final draft of a UN brochure about South Sudan: ‘The key message is that in South Sudan, people are young, rural, poor, uneducated and lack basic services… Our brand is that 15-year-old girl who has a greater chance of dying in childbirth than finishing school.’

The South Sudanese pound features the image of the late John Garang, the deceased leader of South Sudan’s independence movement. The currency was designed and printed by De La Rue Currency, a British security printing firm that has been involved in the design or production of over 150 national currencies. Planeloads of the South Sudan pound arrived from Germany on July 13, 2011.

Like the design of the coat of arms, the primary motif is derivative. The tree metaphor executed in the stilt-and-canopy can be seen in the design of the Queens Botanical Garden Visitor Center, the Qatar Science and Technology Park, or Zaha Hadid’s apartment complex in Vienna, to name a few. Elke Selter, an archive specialist for the United Nations Office for Project Service, which oversees any type of infrastructure building and construction in South Sudan, was the coordinator for the selection process that led to the design of the Archive. When asked if she likes the winning design, she says, ‘It’s good, but I think there were opportunities for innovation that were missed. “Developing-world architecture” has no architect; the engineer is in charge and he works from a master plan. When else do you get the opportunity to get to design from scratch?’

In spite of the evident pride in their new national identity, finding a locally made souvenir in South Sudan is not as easy as might be imagined, but JIT (Just-in-Time), a local supermarket owned by a friendly Indian man, seemed promising. His store was simple but fully stocked, a veritable paradise of convenience goods mostly imported from Uganda or Kenya, including an impressive array of aerosol mosquito sprays in a wide variety of scents. When asked if he had anything ‘Made in South Sudan’ the owner paused and shook his head, glancing apologetically at the generic ‘Juba Jungle’ baseball caps and bric-a-brac manufactured in China.

His eyes light up. ‘Actually, yes,’ pointing to the last aisle. ‘You can buy a South Sudan flag. So far that’s the only thing they’ve made here.’