Thresholds of Silence

Ancient wisdom and modern art come together in an innovative project to reduce the noise pollution produced by Schiphol airport.

Cover photo: Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is located in one of the most densely populated areas of the country, and aircraft noise is a problem in the surrounding cities. Low-frequency ground noise created at take-off is especially difficult to combat because standard noise barriers are largely ineffective against it. Schiphol is implementing acoustical landscaping in the form of large ridges that dampen longer wavelengths.

It is a brisk December day. We are travelling southwest from Amsterdam through Haarlemmermeer. It is polder country, a spacious lowlands that used to be the bed of a vast lake. Broad and flat, it was an ideal place to build an airport, and indeed in 1916 the Dutch military built an airport here which later expanded and evolved into Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, a primary air traffic hub not only for the Netherlands, but for Western Europe as well.

Haarlemmermeer, however, also proved to be ideal for other purposes, and Schiphol is surrounded by extensively developed areas, including relatively large cities and agricultural zones. This is one of the most densely populated areas of the country, and the noise produced by the airport is a problem that has plagued several thousand people in the Haarlemmermeer Municipality, especially in its main town, Hoofddorp.

When you think about aircraft noise pollution, the first thing that comes to mind is often the roar of planes in the sky overhead, but as we cross the polder, we can hear the annoying low-frequency drone called ground-level noise. This is the rumbling din produced mainly during take-off, a noise that propagates just over the surface of the earth. When Schiphol planned the construction of its longest runway, the 3.8km (2.4 mi.) Polderbaan, they publicised its outlying location as a measure that would reduce the impact of ground-level noise on the surrounding communities, but in the end the problem was actually exacerbated. Ground-level noise, particularly in Hoofddorp, but also to the north in Halfweg, Spaarndam and Beverwijk, and even 28km (17.4 mi.) from Schiphol in Castricum, became a perpetual nuisance that ignited years of discussion regarding environmental norms and governmental regulations.

Ground-level noise is notoriously difficult to control, defying conventional sound barriers, but in this agricultural area, farmers have known for centuries that a ploughed field with deep furrows produces a deep, restful silence. By contrast, the flat, dense polder serves as an enormous soundboard, especially in winter when the ground is hard and bare. Jet engines on the Polderbaan, straining at full power to take off, send a booming roar surging out across a level plain that features no hills, valleys or other obstacles to hinder it.

Because the Netherlands is one of the world’s most densely populated countries, and Schiphol is one of the world’s busiest airports, innovative solutions are necessary to moderate the noise pollution in the area surrounding the runways.

This observation was the starting point of a collective effort by a number of organisations to realise an innovative project in Haarlemmermeer. The group includes Schiphol airport itself, the Municipality of Haarlemmermeer, the city of Hoofddorp, and Stichting Mainport en Groen, a foundation which manages much of the land around Schiphol and is dedicated to the creation of recreational facilities in this area.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.The group engaged research institute TNO Delft to do a preliminary technical study of the effect of the plough furrows on the noise levels. The results were indisputable: the furrows, combined with vegetation, could produce a sizeable noise reduction. H+N+S Landscape Architects began to create long parallel ridges over the 33-hectare area between the Polderbaan and Hoofddorp. The result, while extremely functional, was not very inviting. Could the area be made more attractive, more amenable to recreation and leisure activities? Enter landscape artist Paul de Kort.

In the Netherlands we have been organising and orchestrating our landscape for centuries. We reclaim land and then flood it again; we push water back or drain it away. But de Kort is inspired by nature, often working from historical maps to rediscover the original contours of the land. In his words, ‘natural forces, guided by the laws of nature, make wonderful drawings in the landscape, such as the ripples left behind on the beach by the wind and waves’. De Kort transformed the long, sterile stretches of the ridges into a playfully convoluted landscape, and the new project was christened Buitenschot Landscape Art Park, A Soundscape for Schiphol-Hoofddorp.

In 2012 more than 51 million passengers passed through Schiphol on one of the 437,904 flights to and from destinations as diverse as Seattle, Curaçao, Hong Kong, Islamabad and Lagos. That’s an average of about 1,200 flights every day, or one flight every 1.2 minutes.

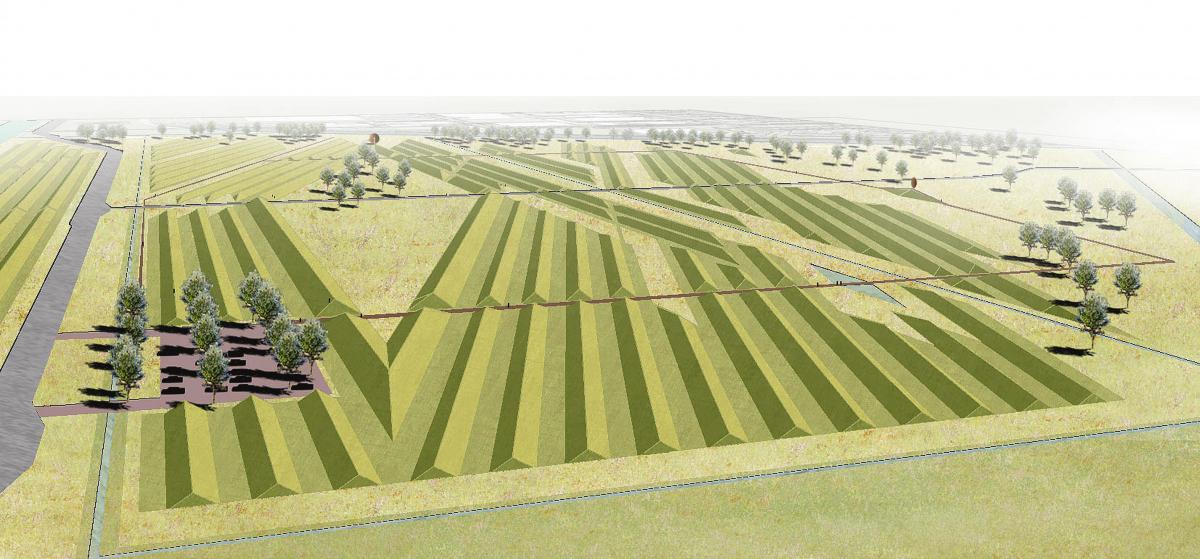

The 33-hectare project includes a series of wedge-shaped hills extending 1.5m (5 ft) above ground level and 1.5m below, as well as tree barriers and other vegetation. This landscape, proven to significantly reduce noise levels, also provides a place for recreational and cultural activities. (Photo: Paul de Kort)

On this brisk December day I am standing with de Kort somewhere between the Polderbaan and the north side of Hoofddorp. It strikes me just how immense the former expanse of water was, a sort of inland sea. The two control towers of Schiphol rise high above the horizon. Excavators with heavy machinery guided by precision GPS are ‘ploughing’, creating enormous ridges 1.5m (5 ft) high flanked by furrows equally deep. The ridges are absolutely straight, laid out at right angles to the direction of the noise and spaced 11m (36 ft) apart. The freshly dug polder clay is grey, like the winter sky above us. It shines, creating a landscape of contrasts: light and shadow, ridge and furrow, art and science, past and present. The dense, heavy earth meets the elusive, yet no less intense, forces of noise. ‘Ground-level noise crumbles, as it were, in the spaces between the furrows,’ says de Kort, and indeed when you enter those spaces it suddenly becomes very quiet. TNO Delft confirms that the structures reduce noise by two to three decibels (out of an overall target of 10dB over the entire area between the Polderbaan and Hoofddorp): a significant contribution.

De Kort calls the ridges ‘thresholds of silence’, and his vision is an exciting and ingenious ‘rising and falling wander-landscape. We are going to call the sheltered spots between the ridges “chambers”, where people can hide themselves away, as it were, in the seclusion of the new, undulating landscape.’ In this parkland with its earthen ridges, the sight lines create a fascinating experience of space and perspective. The long ridges, rising to approximately eye level, draw one in. This design transforms the area into a work of art that de Kort titles Groundsound. In the final phase, two ridges will by topped by pieces of art that de Kort calls Listening Ear, parabolic dishes large enough to stand in. At the focal point of the parabola the ambient noise is amplified as if you were cupping your hand around your ear, and de Kort says, ‘In this way, I want to give form to the meaning of sound and sound waves. They become visible, as it were, in the giant dishes.’

The deep sensation of silence in the middle of a freshly ploughed field comes as no surprise to Dutch farmers. They have known about it for centuries.

Construction of Buitenschot Landscape Art Park began in summer 2012 and is planned to be completed by the end of 2013, when it will be opened to the public. The project transforms the area around the airport into a giant sculpture that reduces ground noise and provides a venue for recreational and cultural activities. (Artist impression by H+N+S Landscape Architects.)

The project embraces other landmarks in the vicinity of the airport, including a 10km (6.2 mi.) dyke and a former fortress converted into a gallery. In this way, new possibilities for culture and recreation will be created in the immediate proximity of the airport, giving Buitenschot Landscape Art Park potential to achieve international appeal.

Support for the project, however, has not been universal. A few house owners on the edge of the area objected, and the farmers in the area next to the Polderbaan also lodged a complaint against the plans. Standing here amidst all these landscapers and earthmovers, we are joined by a man who farms the area around the Polderbaan. He tells us that he has lost precious arable land because the steep slope is almost impossible to mow, useable now only as a sheep pasture.

Still, opponents have at least admitted that the thresholds of silence constitute a project that is unique in all the world. ‘There is a chance,’ says de Kort, ‘that this idea is interesting for exporting abroad to the surrounding areas of airports with similar problems.’ In the meantime, a unique alliance has been created between land and landscape, art and technology, commercial and civic interests, sound and silence.