The Box That Shrank the World

The lowly, inelegant container has been the key to a revolution that continues to shape the everyday lives of nearly everyone in the world.

There is, let it be said, nothing remotely sexy about a shipping container. Six sheets of steel welded into a box with boards for a floor and a couple of doors at one end: transportation equipment doesn’t get any more basic. Yet since the first modern container voyage in April 1956, the container has helped transform the world economy. By dramatically lowering the cost of shipping goods, the container made possible a vast expansion of international trade. It destroyed the economies of ports from Liverpool to Brooklyn and gave rise to entirely new ones. It eliminated millions of jobs on the waterfront and reshaped the very nature of manufacturing. It enabled China to emerge as a world power. Without the container, there would be no globalisation.

The containership Maersk Dieppe approaches Hong Kong’s Kwai Tsing Container Terminals, the third-busiest container port in the world. Today there are approximately seventeen million containers of various sizes in use worldwide. (Photo: Lam Yik Fei / Bloomberg)

Containers ready for shipment from the Port of Rotterdam, the largest port in Europe. From 1962 until 2002 it was the world’s busiest port, but has since been overtaken by Singapore and Shanghai. (Photo courtesy of European Container Terminals.)

The shipping container is a squat box of welded steel that has devastated some markets and professions while giving rise to new opportunities both just around the corner and half a world away.

Before the container, trade across the oceans involved an arduous process called break-bulk shipping: each time cargo had to be shifted from one mode of transport to another—from a railway wagon to a lorry, or from a lorry to an oceangoing vessel—the bulk shipment had to be broken up and each item handled individually. This was far from simple. When the merchant vessel SS Warrior sailed from the United States to Germany in 1954, it carried 194,582 separate bags, barrels, wooden crates and paperboard cartons. In Brooklyn every single item had to be moved from a truck or train into a warehouse near the dock, taken from the warehouse and lowered into the ship’s hold, and then manhandled into position so that it would not shift in heavy seas. Upon arrival in Bremerhaven the process was reversed: dock workers manoeuvred each of those 194,582 items to the opening beneath the hatch, hoisted them from the hold onto the dock, hauled them from the dock to a nearby warehouse, and then painstakingly placed each piece of cargo aboard a lorry or a freight wagon. Although the transatlantic voyage took only ten and a half days, some of the cargo spent more than three months in transit. Loading and unloading the ship accounted for more than one-third of the total cost of the voyage.

All that loading and unloading meant that break-bulk shipping was a very labour-intensive business. New York and London, the world’s two largest ports, each had more than 50,000 registered dockworkers in the early 1950s. On one day the urgent need to unload perishable cargo could create jobs for all comers. The next day there might be no work at all. A port needed a big labour supply to handle the peaks, but on the average day the demand for workers was much smaller, and dockers had to beg for jobs each morning in a humiliating selection process. The constant risk that there would be no work tomorrow shaped tightknit communities built around the docks, where generations of fathers and sons had earned their living by loading ships. The dockers’ unions were reflexively opposed to automation because they knew that substituting machines for muscle-power would eliminate dockworkers’ jobs.

Traditional break-bulk shipping involved unloading thousands of individual packages from trains or lorries at port and transferring them one by one to a ship (and vice versa). In 1956 American entrepreneur Malcom McLean began loading whole containers onto ships, reducing shipping costs to less than 3% of the break-bulk price. (Photo: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The cumbersome process of moving freight made international trade very expensive. On average, freight charges accounted for 10–30% of the cost of imported goods. Insurance was costly as well because cargo was frequently damaged or stolen en route. While American factories exported machinery and French vineyards exported fine wines, sending goods across the ocean was so costly that inexpensive products were not worth trading. French women wore skirts and blouses made in the Sentier district of Paris. American women wore skirts and blouses made in the high-rise lofts of the Garment District in New York City. Only the highest-quality garments were traded internationally because the high cost of shipping was a barrier to trade, raising the price of imports and thus protecting domestic manufacturers everywhere from foreign competition.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Viewed from the 21st century, the solution to the problem of high freight costs seems trivial: instead of loading hundreds of thousands of separate items aboard a ship, why not pack the individual crates and cartons into big boxes and put the boxes on the ship?

This was not a new idea in the 1950s. Canal boats had carried wooden cargo containers in the 18th century, and railways and ship lines in Europe, Australia and America had transported steel containers since the 1920s. The trouble was that those containers did not lower the cost of shipping freight. They usually made a single one-way trip and then were broken up or abandoned, because at the destination there was no easy way to find a shipper with freight headed back to the container’s point of origin. Nor was there much saving of labour costs: to load one of those early containers aboard a ship, a worker on the dock had to prop a ladder against the side, climb atop the container, attach a hook to the steel eye in each corner, and climb down again; after a winch lowered the container into the hold, other dockers would have to climb atop it, remove the hooks, climb back down, and then shove the metal box into place alongside all the barrels and bales and crates. Containers were a nuisance to handle and left wasted space in the ship’s interior. ‘Cargo containers have been more of a hindrance than a help,’ a leading steamship executive complained in 1955.

The solution to this conundrum came from a man who knew nothing about ships. Malcom P. McLean, born in 1913 in a small town in North Carolina, in the United States, was a trucker by profession and an entrepreneur by inclination. Starting with a single truck in the depths of the Great Depression, McLean had built one of the largest road haulage companies in the country. His trucks operated mainly in the north-eastern part of the United States, from North Carolina to Boston. There were few motorways in the early 1950s, and McLean grew increasingly concerned that highway congestion would delay his trucks. In 1953 he came up with the idea of buying ships to ferry truck trailers up and down the Atlantic coast. But after acquiring two ship lines, McLean realised there was a better way. Instead of carrying truck trailers, McLean’s ships would carry only the trailer bodies, leaving the chassis and wheels behind. The wheels would waste precious shipboard space, whereas trailer bodies could easily be stacked, allowing many more of them to fit on a single vessel.

Unloading of merchandise at the Handelskade in Willemstad, Curaçao. Although the ocean voyage took only ten days, some of the cargo spent more than three months in transit. Loading and unloading the ship accounted for more than one-third of the total shipping costs. (Photo courtesy of Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

The driving force of the worldwide containerisation revolution was Malcom P. McLean, a shipping magnate who had started out driving a single truck in a small town in rural North Carolina during the Great Depression.

McLean bought two well-used tankers and installed steel frames to hold containers above the deck. On April 26, 1956 a crane in Newark, New Jersey, just across the harbour from New York City, lifted 58 aluminium truck bodies aboard the SS Ideal X. Five days later, the ship steamed into Houston, Texas where 58 trucks took on the metal boxes and hauled them to their destinations. When McLean’s accountants ran the numbers, they pegged the cost of loading the SS Ideal X at 15.8¢ per ton, a tiny fraction of the US$5.83 it cost to load one ton of freight aboard an average break-bulk ship. Unlike previous efforts, Malcom McLean’s version of containerisation saved money.

Yet containerisation did not take the world by storm. On the contrary, it met with intense opposition. Railways, road hauliers and ship lines all feared that the container would make their business plans obsolete and force them to invest in expensive new equipment. Dockers’ unions from Australia to Venezuela protested that the new technology would eliminate their members’ jobs, often walking out on strike when a containership called. Transportation regulators blocked efforts to pass the savings from containerisation on to shippers by insisting that freight rates be based on the commodity inside each container, even though a railway or trucking company faced the same cost to transport a container of furniture as a container of cigarettes. Traditional ports such as New York, London and San Francisco tried desperately to preserve break-bulk shipping because their old-fashioned piers and narrow streets were ill-suited to handle containers.

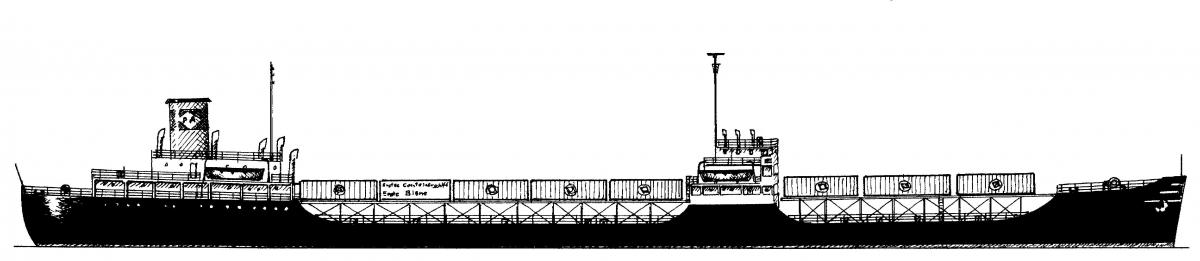

In 1956 McLean bought two World War II T-2 tankers, which he converted into containerships. Renamed the SS Ideal X, this ship carried 58 containers from Newark, NJ to Houston, TX on its first voyage on 26 April, 1956. The ship remained in operation for nine more years and was eventually scrapped in Japan. (Drawing: Karsten Kunibert)

Shippers, meanwhile, were facing a jumble. Following the SS Ideal X’s first voyage, many major ship lines and railways had developed their own containers. Some were 17 feet (5.18m) long, some 28 feet (8.53m), some 35 feet (10.67m). The vast majority of the 58,000 privately owned containers in the United States in 1959, however, were less than 8 feet (2.44m) long. This variety threatened to nip containerisation in the bud. If one transportation company’s containers would not fit on another’s ships or railway carriages, each would need a vast fleet of containers exclusively for its own customers. A European railway container could not cross the Atlantic, because US trucks and railroads could not accommodate European sizes, and a container owned by the New York Central Railroad could not readily be transferred to the Missouri Pacific. Looking ahead, each ship line would need its own cranes in every port, no matter how small its business or how infrequent its ships’ visits, because other companies’ equipment would not be able to handle its boxes. It took years of painful negotiations before major ship lines agreed on a standard container, a box 40 feet (12.19m) long and 8 feet (2.44m) wide, with a standard steel fitting in each corner so it could be lifted by any crane anywhere.

Once the standard was set, container shipping boomed. During a few short weeks in the summer of 1965, shipowners in the United States and Europe announced no fewer than 26 projects to convert break-bulk ships into containerships. The first containerships crossed the Atlantic in 1966, doing a brisk trade in Scotch whisky and the household goods of US soldiers stationed in Germany. The cost savings were so staggering that within three years almost all trade across the North Atlantic was moving in containerships.

Two years later, the story repeated itself in Japan. As new containership services linked Japan and California, the impact on trade flows was immediate. Japanese seaborne exports, 27.1 million metric tons in 1967, soared to 40.6 million tons in 1969, the first full year of container service across the Pacific. The value of Japanese exports to the United States leapt 21% in 1969 alone as Japanese televisions and cameras flooded into America.

Containers reached Hong Kong in 1969, Singapore in 1972. Again, trade soared as a story similar to Japan’s was repeated along the Pacific Rim. Korean exports to the United States trebled between 1969 and 1973 as lower shipping costs made Korean textiles and clothing competitive in the US market. The value of Hong Kong’s foreign trade rose 35% between 1970 and 1972. Taiwan’s exports trebled in three years, and its imports doubled. The combination of ever-larger ships at sea and new enthusiasm from railways and truck lines, which were reshaping their businesses to handle containers efficiently on land, brought faster service and lower costs not just from port to port, but between inland points half a world away.

Although he started with a single pickup truck in 1934, McLean had the second-largest US trucking company (McLean Trucking Co.) by the late 1950s, and had also acquired the Pan-Atlantic Steamship Company. ( Image courtesy of Garry Nelson.)

Cheaper freight brought a boom in trade of a sort previously unknown. Inexpensive Australian wines, Brazilian shoes, and Malaysian shirts found their way onto store shelves in Europe and North America. Salmon farming developed into a major industry in Chile, thanks to refrigerated containers that made it possible to ship the fish to consumers thousands of kilometres away. Eating strawberries and mangos in the middle of winter, unthinkable before the 1970s, became routine thanks to container freight.

In 1986, when China decided to open its economy to foreign investment, its strategy of producing low-value manufactured goods was predicated on the availability of low-cost containership service. Exporting cotton socks, wind-up alarm clocks and tiny replicas of the Eiffel Tower to North America and Europe was practical only because shipping the goods cost next to nothing. The Chinese government understood the importance of cheap freight, investing massively to build and expand container ports. In 1990, Hong Kong, then under British control, was the only Chinese port ranked among the world’s leaders. By 2011, six of the world’s eight largest container ports were located in China, and millions of manufacturing workers in other countries had lost their jobs in plants that could not compete with Chinese factories.

The standardised container has revolutionised not only shipping, but manufacturing and international trade. It has changed the design of ships, waterways, ports and factories.

The container changed not just where things were produced, but how they were produced. The pre-container era was marked by vast integrated factories. At the most famous of these, Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant near Detroit, raw materials like rubber, sand and iron ore arrived at one end and were made into the gaskets, windscreens and engine blocks that the Rouge assembled into finished automobiles. Such huge plants made sense when transport costs were high because they eliminated the need to ship parts and components around the country. But with containerisation, manufacturers no longer needed to have factories that did everything. Large integrated plants were replaced by small ones that specialised in particular products such as synthetic resins or ball bearings and sent their output to other factories for further processing.

These supply chains gradually stretched across oceans. By the 1990s, finished consumer goods such as shoes and television sets filled less than a third of the containers arriving at ports such as Los Angeles. Most of the incoming containers held factory inputs from Asia intended for further processing in the United States. Freight rates were low enough that it even made sense to export American waste paper to China for recycling.

The container transformed shopping too, as retailers discovered that they could cut out the wholesalers that had stood between manufacturers and consumers. With modern communications and container shipping, a clothing chain in Britain could design a dress and transmit the pattern to a factory in Bangladesh which could use local labour to sew Chinese fabric made from American cotton and add Indonesian buttons made from Taiwanese plastics. The finished order, loaded into a 40-foot container, could reach shoppers on Oxford Street in less than a month at prices far lower than any domestic manufacturer could offer.

A 40-foot (12.19m) intermodal container. All eight corners of this steel box have twistlock fittings for stacking, locking and craning. Container sizes have been standardised since 1961 so that containers can be transported efficiently by ship, rail and lorry, saving space, expense and time. (Photo courtesy of European Container Terminals)

Globalisation, while vital to the growth of developing countries, has been controversial in rich ones. Most frequently the Asian manufacturing boom is attributed to low wages and oppressive working conditions that enable Asian factories to undercut competitors in wealthier countries. But if low labour costs were the decisive factor, manufacturers would have shifted production to China and South East Asia decades ago. It took the container to make globalisation possible by reducing the high transport costs that were such an impediment to trade.

The container revolution is not over. Ships continue to get larger; the latest can carry 9,000 40-foot containers, more than 150 times the capacity of the SS Ideal X. The Panama Canal, that key artery between the Atlantic and the Pacific, is in the midst of a US$5.25 billion expansion to handle bigger ships, but when that project is completed in 2015, dozens of the newest containerships will still be too wide to pass through. Ports are getting larger, too. Europe’s largest ports, Rotterdam and Antwerp, are undertaking huge new investments to move the thousands of containers that will need to be off- and on-loaded each time one of the giant new vessels calls. Cranes are getting taller—the newest stand over 130m (426.5 ft) high—and faster, with some able to move a container from ship to shore every 90 seconds. And around the docks, where the containers move like clockwork, people are becoming ever scarcer. The most modern container terminals use computer-controlled stacker cranes to pluck containers from incoming trucks and deposit them in a specified storage location where driverless vehicles pick them up and move them from the storage area to the pier. Dockworkers are less likely to be found near a ship than in nearby offices, where they use computers to plan the most efficient way to load vessels, and write programs that tell the automated vehicles what to do.

Meanwhile, the great lessons of the container revolution—that standardisation and scale are the keys to lower costs and higher profits—have been absorbed by entrepreneurs who have never set foot on a wharf. Computer companies have created data centres in a box, ready to deploy in an instant. Architects are designing apartment houses and shopping centres assembled from containers. Oil companies are using the concepts of containerisation to design modular pipelines that are easy to assemble. A portable art gallery in a container may be coming soon to a neighbourhood near you. Nearly six decades after the famous voyage of the SS Ideal X, the container continues to change the way the world works.