Designing For The End

When life, or even the whole world, seems to spin out of control, the designers who try to prepare us for the worst offer a measure of dignity and hope.

Cover Photo: A satellite image from March 18, 2011 showing damage after an earthquake and tsunami at Fukushima Power Plant, Japan. (Photo: DigitalGlobe)

No one plans a disaster. Then a porcelain cup falls. The sea rises. Your heart breaks. Or stops.

Disasters may seem as unfair as they are inevitable. From the Italian roots dis (ill) and astro (star), a disaster can be unleashed by forces far beyond our control, impossible to escape, leaving no alternative but to hope for the best when it strikes.

Some disasters, however, can be designed—at least in part. Unable to actually prevent all operating system errors, Microsoft Windows offers the Blue Screen of Death, the unmistakeable colour signalling a problem otherwise inexplicable to the lay user. Helpless to forestall all possible crashes, aircraft designers at least supply the black boxes that withstand and witness them. Across different industries, a constellation of anticipatory structures can shape disastrous events, in the hope of producing minor improvements to the human experience such as a ‘good’ death or a clean break. On scales as widely varied as an individual death, a collective tragedy, and the destruction of the planet, designers, architects and engineers work to give form to disasters, offering a startlingly romantic view of humankind’s ability to face the future.

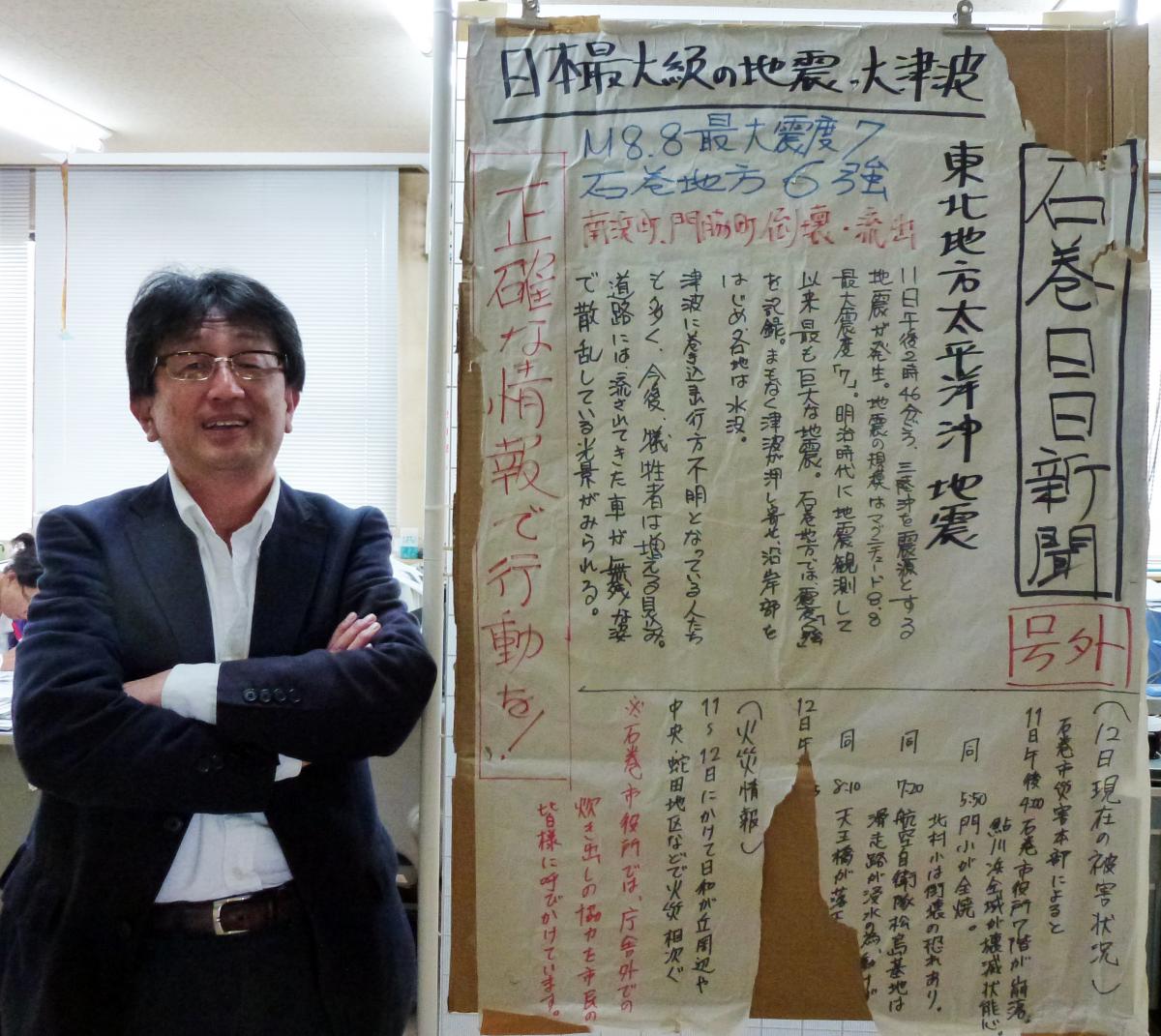

Hiroyuki Takeuchi, chief editor of the Ishinomaki Hibi Shimbun newspaper, poses next to their March 14, 2011 newspaper wall at the company’s headquarters in Miyagi prefecture, northern Japan. When the March 2011 tsunami struck a great swathe of the northeast coast, leaving 19,000 people dead or missing and triggering the Fukushima nuclear disaster, it also flooded the paper’s offices. With its modern technology incapacitated, the town’s only newspaper wrote its articles by hand with black felt-tip pens on big sheets of white paper for six days. (Photo: AFP)

One future that every person faces is the inevitable and yet inconceivable disaster of death. While initiatives like the $1 million Palo Alto Longevity Prize seek to one day end aging, an experimental design studio in London is focused on improving the interim: Helix Centre, embedded within St Mary’s Hospital, seeks to redesign the process of dying.

Statistically speaking, a large number of British people seem to be dying bad deaths, their last moments playing out in a sterile and uncomfortable environment they did not choose. A recent Helix survey reports that even though only 1% of people in the UK say that they want to die in a hospital, that is where nearly half of them are likely to breathe their last. The challenge, according to Ivor Williams, senior designer at Helix, is to create a system in which patients can express how they want to die before they’re actually dying.

You seem to enjoy a good story

Sign up to our infrequent mailing to get more stories directly to your mailbox.Since the 1970s, patients in the UK have been able to register ‘do not attempt CPR’ decisions, so that doctors and first responders do not resuscitate them in a medical emergency, allowing them to die naturally. But except for the miraculous few who have already survived a near-death experience, patients often find it hard to articulate what the words ‘a good death’ mean to them. They may have an idea that they want to prioritise comfort instead of eking out a few more minutes, but actually planning for the possible scenarios can be a daunting task. Doctors, trained (and in many countries, bound by law) to save patients’ lives rather than let them die, can also struggle to guide conversations about death. One article in The BMJ advises medical professionals to avoid awkward words like ‘futility’ and images like ‘hitting a ceiling of care’.

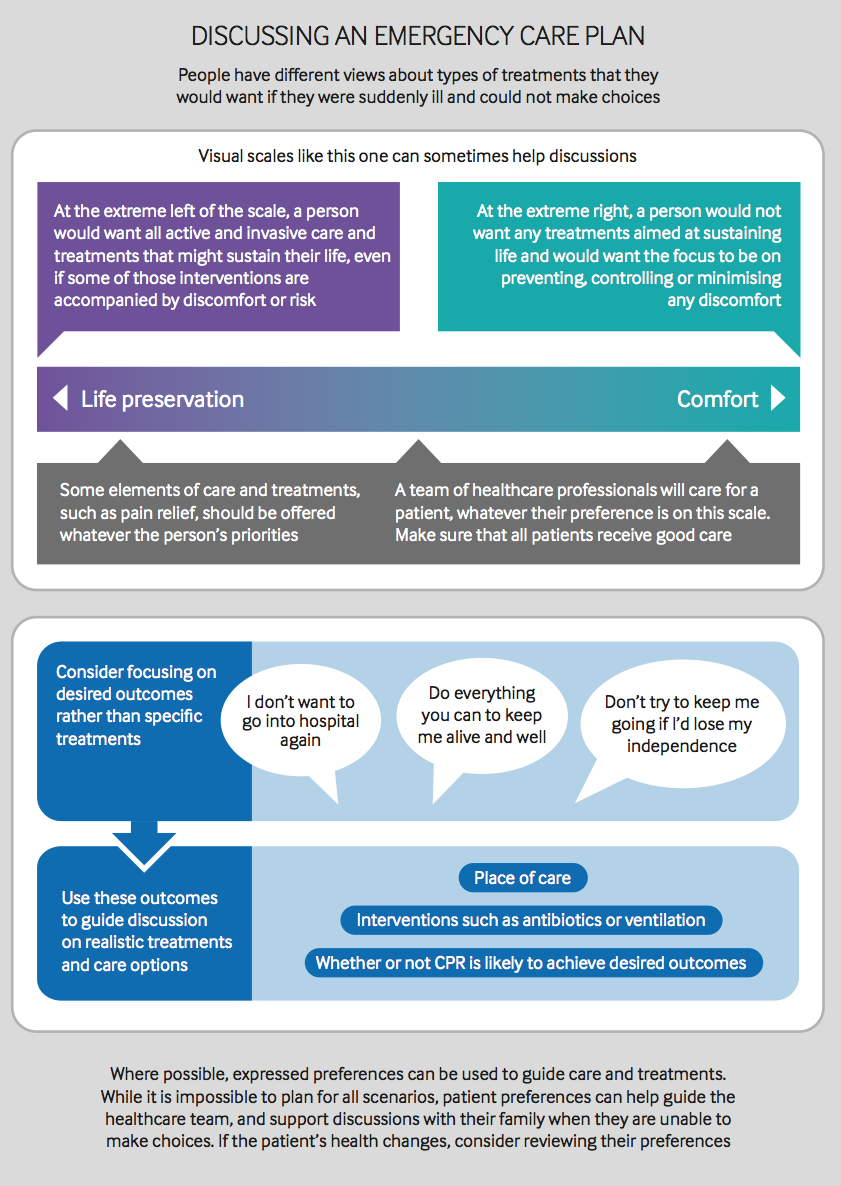

Do-not-resuscitate decisions were first documented in the 1970s and were formalised over time to protect people from receiving CPR that they did not want or that would not provide an overall benefit.  Medical publishing company The BMJ developed an emergency care plan allowing clinicians to discuss and record patient preferences in advance, not only regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but all aspects of care and treatment in an emergency when people might not have the capacity to communicate their preferences. (Image courtesy of The BMJ.)

In February 2017, Helix launched a project to facilitate such discussions, ultimately creating a document called ReSPECT to be shared between doctor and patient. Since February 2017, ReSPECT has been in use in five UK hospitals and is intended to eventually replace the far more alarming ‘do not attempt CPR’ form. Designed to be regularly revised, the gentle violet form summarises a patient’s health condition and allows them to mark along a scale ranging from ‘prioritise sustaining life’ to ‘prioritise comfort’. Perhaps most importantly, the form offers freeform spaces in which patients can use their own words to describe what they mean by ‘comfort’ and what matters most at the end of their lives—already a stark contrast to the jargon-heavy bureaucracy that makes hospitals such alienating places in which to die in the first place.

While communicating about an individual death is a challenge because the situation is at once complex and intimate, handling information about a collective disaster poses challenges of a different scale. Today when a hurricane strikes, terrorists attack or hackers steal data, news organisations are able to gather, analyse and report the information faster than ever. But what is the most effective way to organise and relay that flood of data in a way that worried readers can digest?

In 2012, US news outlet USA Today added a secret template to its website, one to be deployed only in case of a massive disaster. Part of an overall site redesign by Brooklyn studio Anton and Irene, the disaster template was designed to channel incremental breaking news and updates as an event unfolds. Like a folk hero, the page will appear instead of the usual homepage when ‘the next 9/11’ strikes, says the studio’s global creative director Anton Repponen. It has not yet been used.

In contrast, Russian investigative paper Novaya Gazeta once considered taking the design of disaster in a different direction for particularly earth-shaking events, for example if second-term president Vladimir Putin died in office, a major shift for a country ruled, directly or indirectly, by the same man since 1999.

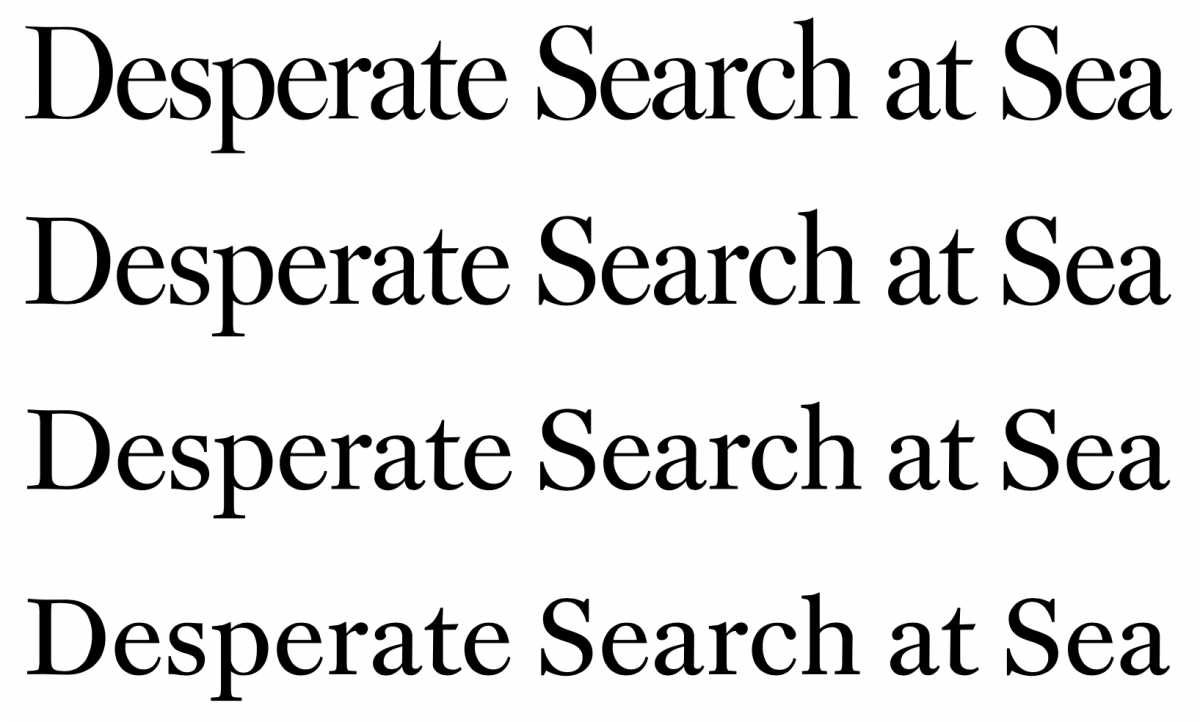

Type designer Matthew Carter created a family of typefaces called Vincent for Newsweek magazine with three size-related versions: Text, Subheads and Headlines. When John Kennedy Jr, his wife and sister-in-law were killed in a plane crash in the ocean in July 1999, Newsweek design director Lynn Staley found that the Headlines font used at the huge sizes appropriate to such a tragic event looked too clumsy. She accordingly commissioned a special version, known internally at the magazine as the disaster font, for especially notable events. The font is used not only for disasters but also for victories, such as when the Red Sox won the World Series or the Patriots won the Super Bowl. (Image courtesy of Matthew Carter.)

Overhauled in 2015 by Moscow studio Charmer, Novaya Gazeta’s regular homepage was originally designed as a minimalist snapshot of the day’s news. ‘The main goal of the front page model was to form a total picture of the day for readers of the newspaper. We were thinking about different content configurations for this feature, so we came up with six or seven layouts, one with one menu, one with two menus, etc.,’ says UX designer Ross Sokolovski, who was contracted to work on it.

But for that day, unlike all others in Russia, Sokolovski proposed a concept radically opposite to the USA Today design of constant updates and fragmentary news: a special homepage would be left completely blank—no menu, no links—except for three momentous words, he recalls. ‘One special layout would have nothing on the screen except the sentence “Putin is dead”. No other information needed.’ (According to Charmer, that concept did not make it to the final site design.)

Still greater disasters unfold not in a day, but over years and decades. One of them grips the globe today, a gradual warming that even now is drying out the earth and expanding the seas. And as climate change threatens to usher in even more furious storms and increased seismic activity, some architects are rethinking not just their designs, but their entire deontology.

On the morning of April 18, 1906, a massive earthquake shook San Francisco, California. Though the quake lasted less than a minute, its immediate impact was disastrous. The earthquake also ignited several fires around the city that burned for three days destroying half of the city, one of the worst natural disasters in US history. (Photo: Records of the United States Senate, National Archives.)

‘[The environment] is going to define the way we practise design, architecture and politics to come,’ says Nadir Tehrani, Dean of Architecture at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York. ‘How do we reimagine sustainability to bring these three forces into conversation such that the next generation can look back on us with kinder eyes?’

Responsibility for anticipating a natural disaster has historically belonged to the state—architects in earthquake-prone countries like Japan, Greece and Indonesia are familiar with the cadence of updated building codes that follow each big quake—but Tehrani suggests that perhaps responsibility should lie with the designer instead, on the frontlines of negotiating an increasingly volatile environment.

During environmental crises, large structures often become impromptu shelters and refuges. Without careful anticipatory design, they may not do the job particularly well; Louisiana’s Superdome stadium became famously hellish as tens of thousands of displaced people took shelter there during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Six people died while sheltering there.

‘The creative challenge is to determine how such infrastructure can fulfil a civic purpose that exceeds its quotidian purpose,’ says Tehrani. ‘In places like New Orleans, civic memory makes that need and vision explicit: resilient infrastructures that respond to contingent needs. But most cities don’t bring this up, not only because they lack the money, but more critically because they lack the imagination to forecast and plan for possible futures.’

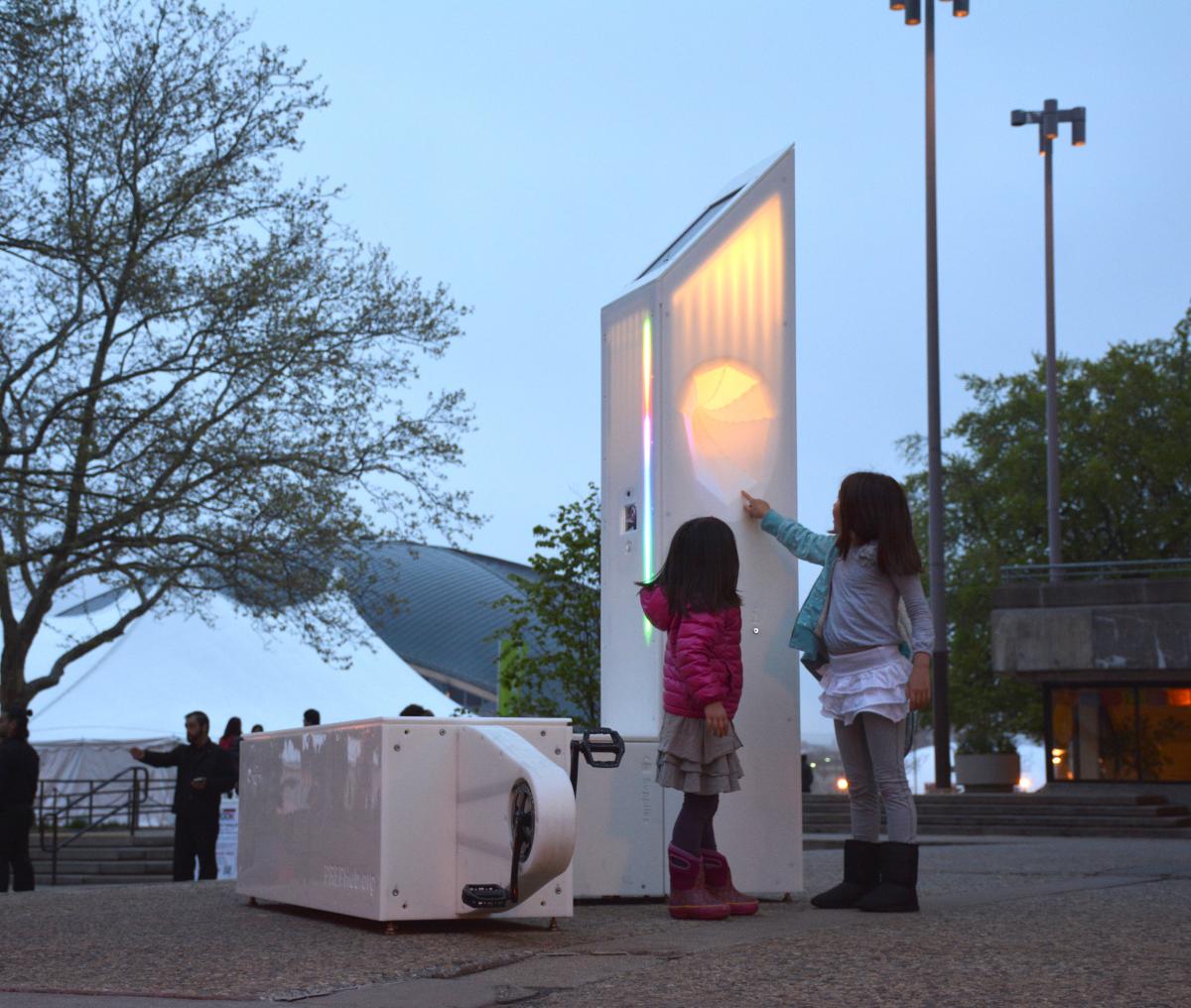

PREPHubs are a new kind of public structure designed to increase disaster resilience. Each component serves the community in everyday scenarios so that when emergencies occur people already know where the equipment is and how to use it. (Photo courtesy of Urban Risk Lab.)

Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Urban Risk Lab offers one example of how an ethical architect can do it on the people’s behalf. Directed by former Office for Metropolitan Architecture associate Miho Mazereeuw, the lab’s research into natural disasters has produced designs for numerous projects, including PREPhub, a universal physical shelter that looks like public art but also offers light, an emergency radio and a movement-powered phone charger—functions, Mazereeuw says, ‘that are designed to work every day, building a community’s familiarity with and usage of the technology. That way, if a disaster strikes, people already know where to go and what to do to get critical resources.’

That may seem like small comfort in an age when the world appears to hover between the threat of global warming and the spectre of nuclear winter, when geopolitical balances shift unpredictably at the slightest provocation and the technological infrastructure that underlies so much of our comfort also opens the door to lurking dangers on a scale never before imagined.

From some angles, our safety and security have never been more fragile, and Silicon Valley’s wildest solutions—like migrating to Mars—can seem perfectly apt. The case studies above, however, offer a different way of thinking, drawing on the very human idea of resilience. It acknowledges the designer’s lack of control and nevertheless tries to offer a little grace and even, perhaps, a little hope.

Of course, for those who are impatient, there is one other available survival strategy for a danger-fraught future: pre-empt uncertainty by scheduling your own end, designing the last day of your life, determining the last stop on your journey, writing the last page of your story—